CQ4: No.1 WRONG assumption on Creativity

In the previous two articles, I explained the Western social and economic landscape in which creativity had a chance to become a valuable ability. This week and next week, I will virtually walk around in your offices and explain some of the ‘creativity talk’ you hear and maybe speak of yourself.

In the previous two articles, I explained the Western social and economic landscape in which creativity had a chance to become a valuable ability. This week and next week, I will virtually walk around in your offices and explain some of the ‘creativity talk’ you hear and maybe speak of yourself.Joy Paul Guilford (Westside)

In California, we meet Joy Paul Guilford (1897-1987). Guilford from Nebraska became an elementary school teacher after high school for two years. Then, after one year at the University of Nebraska, he joined the Army. After being discharged he went back to the same university and obtained his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in psychology. He obtained his PhD at Cornell University in 1927. Later he moved back to the University of Nebraska to become a Professor of Psychology and gained an international reputation. In 1940 he moved to the University of Southern California, where he stayed until retirement (Comrey, 1993).

In California, we meet Joy Paul Guilford (1897-1987). Guilford from Nebraska became an elementary school teacher after high school for two years. Then, after one year at the University of Nebraska, he joined the Army. After being discharged he went back to the same university and obtained his Bachelor’s and Master’s degree in psychology. He obtained his PhD at Cornell University in 1927. Later he moved back to the University of Nebraska to become a Professor of Psychology and gained an international reputation. In 1940 he moved to the University of Southern California, where he stayed until retirement (Comrey, 1993).The ‘start’ of creativity research

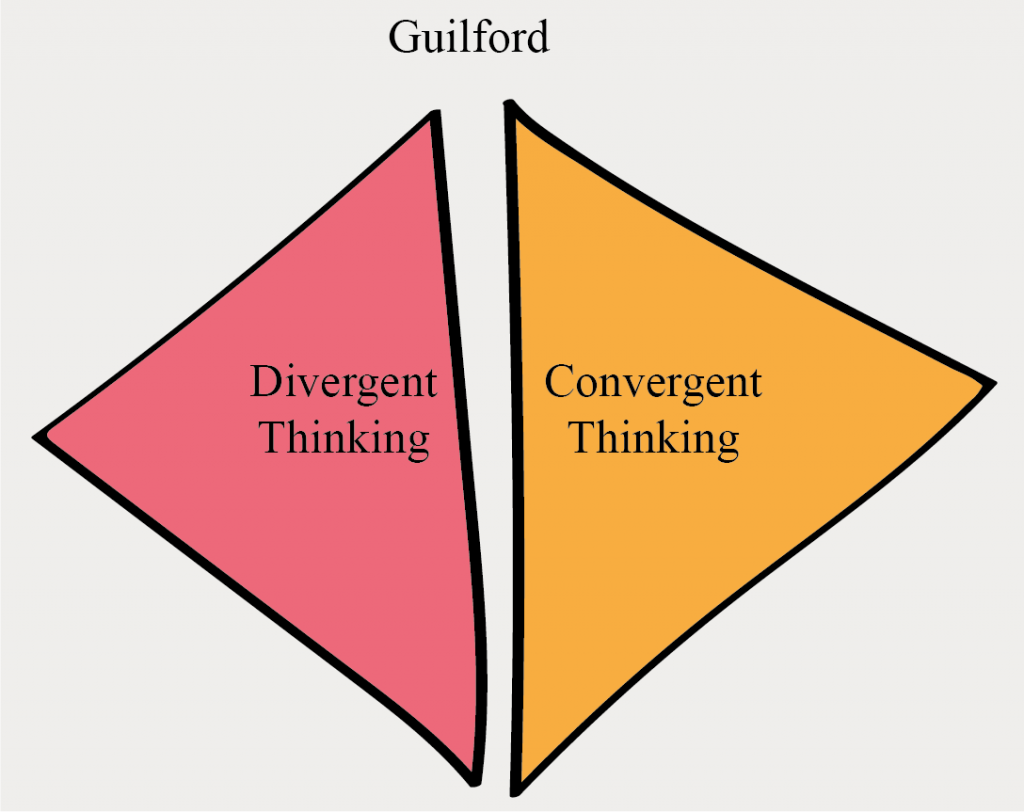

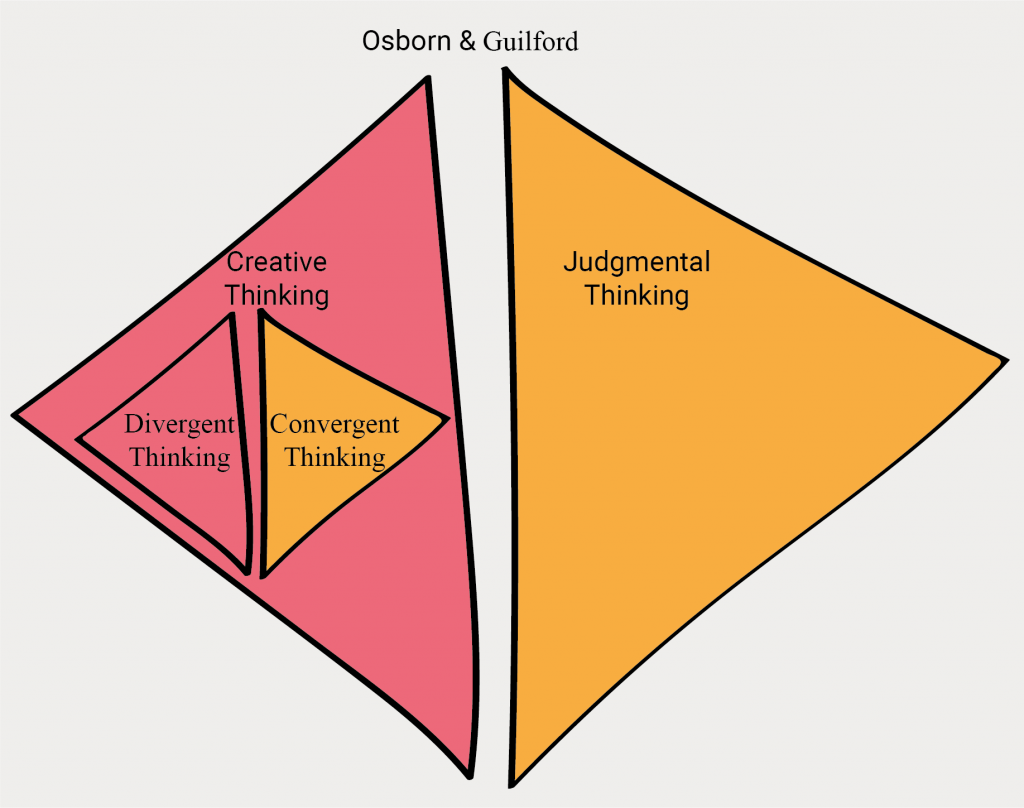

Creative thinking according to Guilford

- Divergent thinking in which one has to consider many options that break with the past (breaking with the past is a notion that was born in the Gestalt Theory on creativity, this will return in chapter two).

- Convergent thinking in which one considers what the best option is.

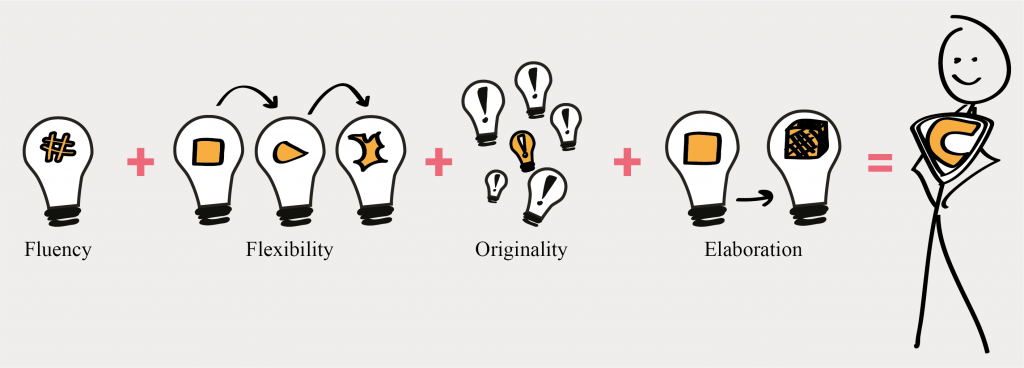

Measuring creative potential

- ‘Fluency is measured by the number of responses;’

- ‘Originality is measured by the number of responses not mentioned by other participants;’

- ‘Flexibility is a measurement of the number of different categories that that responses group into; ’

- ‘Elaboration is a measurement of how descriptive each response is’.

The higher you score on the four factors, the higher your creative potential. You can ask yourself all kinds of scientific questions about the validity and reliability of these measurements. That discussion I leave to the psychometrists experts. Nowadays there are many divergent thinking tests. The most famous one is the Torrence Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT), created by Torrence who bases his test on Guilford’s work. The TTCT is still the standard to measure creative potential.

Please note: Guilford said creative thinking exists out of two parts diverging AND converging.

Diverging AND converging: judging is part of creativity

Walking around in your offices and talking to creative professionals or ‘creative leaders’ I conclude that the general assumption is that creativity=divergent thinking=ideation like I said in the introduction of the article. A worse variant on that is: ‘you need creativity for divergent thinking’. It is more like the opposite: you need divergent thinking for creativity.

You, in the general term, maybe not you as the reader, seem to think that creativity happens in the diverging part and judging happens in the converging part. This is WRONG. The judging is part of creative thinking and should not be separated from it.

There are even scientists that disagree with Guilford’s assumption that diverging is even part of creativity (Weisberg, 2006). But I cannot find any literature (and of course that could be me) that argues that convergent thinking, judging, is NOT part of creative thinking. And it makes perfect sense. If you want to create, you have to make a choice. That is part of the creative thinking process.

Why do we think that only diverging is part of creative thinking?

The simple answer is that Guilford was focusing on the diverging part of creative thinking. It is a misunderstanding, also among scientists that divergent thinking tests measure creativity (Runco, 2010). So we are not alone in our assumption.

But why I think we, as practitioners of creativity, have this assumption doesn’t have its foundations in science. This is where we need to leave California to take the train to Buffalo, New York. I hope it’s Summer.

Alex Faikney Osborn (Eastside)

In Buffalo, New York, where we shake hands with Alex Faikney Osborn. Nice, the sun is out, Springtime.

In Buffalo, New York, where we shake hands with Alex Faikney Osborn. Nice, the sun is out, Springtime.

Alex Osborn (1888-1966) is a typical case of The American Dream. Scraped his way through college (psychology), fired at his first job and later became the director of advertising company BBDO from New York City, employing over 1000 people at that time. Then he created a business from his hobby: imagination. He says it is all because he saw the value of ideas that he became so successful (Osborn, 1948). And what do you do when you are successful? Exactly, you write it down. Osborn has written four books on creativity:

- 1942: ‘How to think up’. Only 38 pages, at least according to Google Books. Looking inside the book he mentions brainstorming once but doesn’t explain it as far as I can tell. I tried to buy the book but I found it impossible to find. Let me know if you have a copy!

- 1948: ‘Your Creative Power’. First ‘real book’. He tells us his own creative journey. And very important for history and for us, it is the book in which he explains brainstorming. He sets the rules, and he gives the criteria for the situations in which brainstorming could be a good method to use. The rules survived through history, the criteria did not. The latter is making brainstorming a misunderstood method. More on brainstorming in chapter 7.

- 1952: ‘Wake up your mind’. And the subtitle: ‘101 ways to develop your creativeness’. How is that for a word: creativeness. I don’t know anything about this book. The title suggests that it is one of the first tool books with creativity techniques.

- 1953: ‘Applied Imagination’. It is a bit similar to Your Creative Power with loads of examples from governments, households, marriages, education, raising children, and business. The Cold War obviously influences his drive to educate people in creativity. Oh and women are also very creative, they have to think up something new to cook every evening… This book differs from Your Creative Power in the way that it gives more tools for brainstorming and also exercises to practise your creative thinking.

If you want to know more about brainstorming you should read Your Creative Power. If you are looking for quotes, read any of them. They are filled with good ones. For example, the ‘Aluminium Company coined “imagineering”: ‘you let your imagination soar and then engineer it down to earth’’ (Osborn, 1498: p5). Imagineering, what an awesome word.

After writing these books Osborn was not done. He founded the Creative Education Foundation in his hometown Buffalo, New York in 1954. And together with an organizational psychologist, Sidney Parnes, he created Creative Problem Solving (CPS) as a method to enhance creative thinking and solve problems. More on CPS in chapter 5. Whatever we think is true on creativity came from Buffalo (and it still does).

Creative thinking according to Osborn

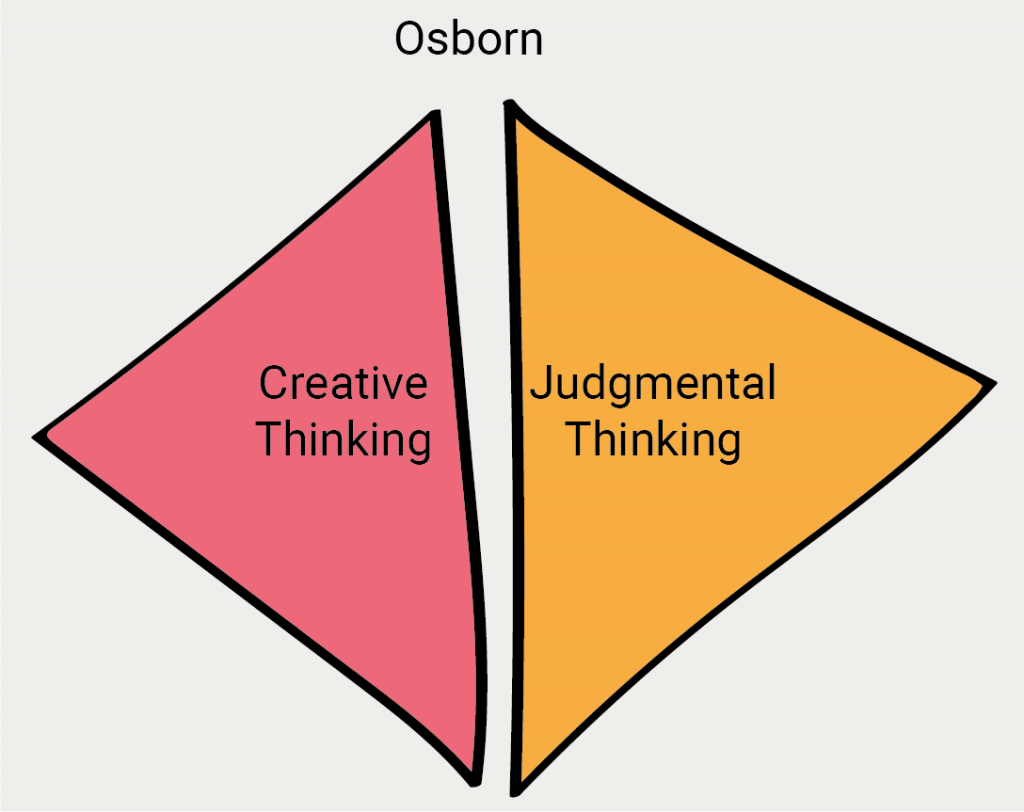

Osborn says in his books (1948, 1953) there are two kinds of thinking used to solve problems:

- Creative thinking: the type of thinking in which you have to use your imagination and generate ideas (ideation).

- Judgmental thinking: the type of thinking in which you have to analyse and criticize.

The first is about creating options, the second it about choosing options. In his opinion, we need more of the first type of thinking to solve pressing societal problems. And to stimulate imagination and thus creative thinking in groups Osborn invented ‘brainstorming’. And one of the rules in brainstorming is that ‘quantity is wanted. The more ideas we pile up, the more likelihood of winners’ (Osborn, 1948, p:269). So, more ideas are better than fewer ideas.

Difference between Guilford and Osborn

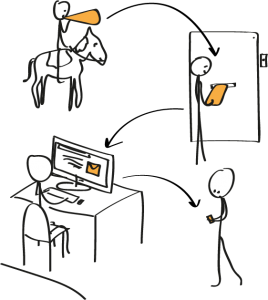

Now it becomes tricky, pay attention. What Guilford calls divergent thinking, Osborn calls creative thinking. Osborn’s definition of creative thinking is lacking the convergent part Guilford attributes to creative thinking. Osborn says that choosing the options is not part of creative thinking, while for Guilford that is part of creative thinking. Osborn’s language made us believe that creative thinking equals idea generation. Maybe the picture below helps. To summarize in a picture:

To summarize in words:

- Guilford: Creative thinking = divergent thinking + convergent thinking

- Osborn: Creative thinking = imagination = idea generation

Why do we also think ideation is the same as divergent thinking?

- Ideating without diverging is about coming up with as many ideas as possible (fluency)

- Ideating with diverging is about coming up with as many ideas as possible (fluency) but also that are different from each other (flexibility).

Conclusions

- Creative thinking is more than divergent thinking. There is at least a judging component to creative thinking.

- Divergent thinking is not ideation. You can ideate without diverging.

- Creativity thinking is definitely more than idea generation.

I hope I cleared the air on this assumption on creativity. It is a tough one. If scientists and also influential organizations like the WEF* use this wrong assumption on creative thinking, we have a long way to go.

*WEF has separate critical thinking from creative thinking, while critical thinking is part of creative thinking.

Even though he was incomplete in his ideas on creativity, Osborn has won the battle so far. Why? Because he was a business man of course!

Back to the Future

Osborn and Guilford lived in the same period. They knew of the existence of each other. How come they never discussed this crucial difference? I need Doc and a Dolorean to go Back to the Future.

Fortunately, I have a colleague at TUDelft, Sam Franklin, who is writing a book called The Cult of Creativity, it will be published by University of Chicago Press. He figures as my Doc.

I asked Sam about the relation between Osborn & Parnes with Guilford. Firstly, Guilford had a completely different motivation than Osborn. Guilford, the scientist wanted to figure out creativity. Osborn, the businessman, wanted to sell his methods. But the latter needed his ideas to be accepted by the scientific community, so he was happy enough when Parnes, a psychologist, wanted to join his quest.

Secondly, in the 1950s there were these creativity conferences in Utah where creativity scientists shared their knowledge. According to Sam, Parnes was not really taken seriously and was more or less tolerated on these conferences. He was put in charge of the development part of creativity, instead of the identification of creativity.

Also if you read current scientific literature on creativity, Osborn and Parnes are only mentioned shortly as a method to develop creativity, if they are mentioned at all…

Take a chance!

21st century, we all want to develop and enhance our creativity. And here we have Osborn and Parnes, who claimed to sell a method that does just that. Osborn and Parnes were smart enough to ‘prove’ their method of Creative Problem Solving works. Even though not really taken seriously by creativity scientists. A shame, if seventy years ago, scientists would have truly tried to see how CPS could be related to the identification of creativity, we could have gained a lot of knowledge.

This article is a call for scientists to look beyond science and see what is happening in practice. And this article is a call for creativity practitioners to be more critical about creativity methods. Just because science and business have a different stake, doesn’t mean that there is not a lot we can learn from each other. Let’s bridge the gap between theory and practice!

Check out the topics of the next two weeks below. Next week, the third card from this quartet about another lovely phrase: ‘Let’s think outside the box!’

Thanks for reading and I wish you a pleasant continuation of your day.

Willemijn

The Creativity Quartet 2020 combines my knowledge on and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering (IDE@TUDelft) in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories.

I provide training in creativity & problem-solving to professionals, and I love to talk about creativity & problem solving on stage. To practice creativity, I also design serious/business games by request (Your Nine Dots) and I teach at IDE@TUDelft.

I do my best to source and summarize correctly. However, if you read anything incorrect or of the hook, please let me know! Ending with my favourite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou: “You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Comrey, A. L. (1993). Joy Paul Guilford. In: Biographical Memoires V.62. Washington: The National Academies Press.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (ed.) (2019). The Creativity Reader. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Osborn, A. F. (1948). Your Creative Power. New York: The Scribner Press, 9th print, 1952.

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking. New York: The Scribner Press, 6th print 1955.

- Runco, M.A. (2010). Divergent Thinking, Creativity, and Ideation. In Kaufman J. C., and Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, pp. 413-446. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ14: What is Creativity?

Understanding how people create has been a serious topic for philosophy since the Renaissance (CQ9). But when Guilford acknowledges creativity to be a

CQ15: What is the difference between creativity and innovation?

I recently became the new President of the European Association of Creativity & Innovation (EACI)*. From that perspective, it would be nice to cla

CQ5: Creativity is thinking outside the box. But which box?

The phrase ‘outside the box’ is often associated with creativity. Besides outside the box thinking, there are outside the box methods, outside the box

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.