Do you know that feeling? That feeling that you found it, that final piece of the puzzle. That puzzle piece that makes everything fall into place. That feeling of completion and illumination. Do you?

Maybe you do, maybe you don’t, maybe a little. Most people never really experience complete illumination. But still, we believe that creativity involves this one idea, that AHA-or, Eureka-moment.

Where does the belief in a ‘moment of insight’ come from and what can way say about it?

In week five I shortly introduced the Gestalt theory on Insight Problem Solving, and I explained where the phrase outside-the-box thinking comes from (CQ5). In this article, I will dive deeper into this part of the Gestalt theory. Let’s see what we can learn from it.

Before we start, important to note is that the definition of creativity in this context is the ‘idea that is of the essence to solve a problem’. So we are talking about ideas and problem-solving.

What is the Gestalt theory?

In 1890 Cristian von Ehrenfels writes an essay called “On Gestalt qualities”. According to Wagemans (2015, p3), Von Ehrenfels argues that:

‘Because we can recognize two melodies as identical even when no two notes in them are the same, […] the forms must be something more than the sum of the elements. They must have, what he called “Gestalt quality”, a characteristic which is immediately given, along with the elementary presentations that serve as its fundament, dependent upon the objects but rising above them.’

So, according to Ehrenfels, we have the tendency to see the whole before the parts. And he calls that Gestalt quality. This is the ‘start’ of the Gestalt theory (Wagemans, 2015).

Phi-motion

In the year the Titanic sunk to the bottom of the Atlantic ocean, the Jewish psychologist from Berlin, Max Wertheimer discovered a phenomenon called phi-motion which is:

‘perception of pure motion […] without object motion’ (Wagemans, 2015: p2).

According to Wagemans (2015), the story goes that Wertheimer came to this idea when he saw the light switch on and off at a railway station. We’ve all seen this waiting at a train crossing. It appears as if the light is moving from left to right and so forth. While the light actually switches on alternately. We see motion without an object moving. This is what he called phi-motion.

According to Wagemans (2015), Wertheimer takes Ehrenfels’ theory a step further and claimed that (Wagemans, 2015: pp.3-4):

‘specifiable functional relations exist which decide what will appear or function as a whole and as parts. Of the whole is grasped even before the individual parts enter the consciousness.’

Now we have a high school understanding of the Gestalt theory, we move to a specific part, on the moment of insight. Read Wertheimer’s (1945) book on Productive Thinking to know more.

Breaking with the past for a moment of insight

In the first quarter of the previous century, the general consensus was that association, Aristotle’s idea (

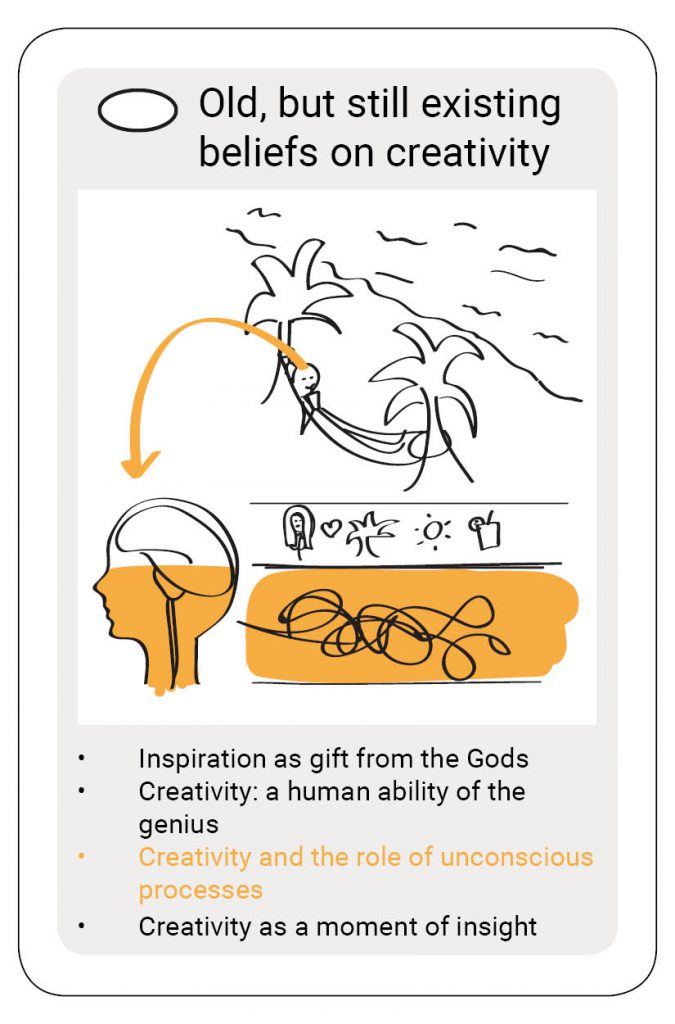

CQ8), was how thinking and problem solving worked. In other words, to be creative, to come with ideas and to solve problems you have to associate. One idea leads to the next, to the next, etc. And in the 1920s the notion that these processes had a great unconscious element was popular (

CQ10).

The Gestalt theorists argued against associatism to solve specific types of problems, named insight problems. Insight problems are problems that need some form of breaking with the past. You need to be able to ‘look differently at the same thing’. (Yes that quote also comes from the Gestalt theory.)

The Gestalt theorists argued that insight happens so fast, it cannot be that an association goes that fast, there must be a ‘leap of insight’ (Sawyer, 2012, p.108) to create a moment of insight.

Prove for a moment of insight

A colleague of Wertheimer, Wolfgang Köhler is the first to experiment with so-called ‘insight problems’ in 1925, not with people but with chimpanzees. According to Weisberg (2006), Köhler’s experiment was as follows: he put a banana outside the cage of the chimpanzee, out of reach of the chimp. So we have a grumpy chimp. Then he puts a stick in the cage of the chimp, in front of him. The chimp ‘realizes’ he can use the stick as an extension of the arm: the moment of insight. If the stick is behind the chimp, he doesn’t make this connection. So if the situation was ‘structured correctly’ the chimp would ‘get it’.

How did the monkey come to the idea to see the stick not as a part of a tree but as an arm-extension? How is it possible that the chimps looked ‘differently at the same thing’? Student of Wertheimer and Köhler, Karl Duncker, explains this phenomenon.

Functional fixedness

According to Sawyer (2012), it was Duncker that first conducted research on creative insight in 1926, a year after Köhler’s chimpanzee experiment. Duncker used 20 puzzles (insight problems) that, according to him, could not be solved by mere association, i.e. incremental steps. If you would use incremental steps, also known as ‘hill-climbing’-tactic you would eventually get no further. This point is what the Gestalt theorists called an impasse. How to get out of this impasse?

Let’s take a look at a famous problem Duncker used in his research (and still used today) to see how we can start moving again after an impasse.

The candle problem

Consider the following problem. You get a candle, a stack of matches, a pinboard and a box of tacks. You have to attach the candle to the pinboard and light it so it can burn normally. Think about it…

Did you think about attaching the candle to the board with a tack? Don’t worry, this is what most people try. It’s not the solution.

Here comes the solution…

To solve this problem you have to remove the tacks from the box and use one of the tacks to attach the tack box to the pinboard. Then put the candle inside and light it. Tada!

In Duncker’s Candle experiment most participants didn’t find the solution. He repeated this experiment, slightly different. This time he removed the tacks from the box in advance and offered the box and the tacks to the participants separated from each other. And what do you think? Most people could solve the problem without much effort. Duncker clarified this difference with a phenomenon he called ‘functional fixedness’.

In the first experiment, the tacks were in the box. Therewith the container function of the box was emphasized. And participants got fixated by this function of the box. As Weisberg (2006, p.297) puts it:

‘this component of the initial structure of the problem had to be changed in order for the box solution to be produced, and the restructuring was interfered with by the presentation of the box in its typical function.’

So if the box is presented empty to the participants, it doesn’t have the ‘container-function’ anymore and so people were not fixated on that function.

Besides functional fixedness, there is also something called structural fixedness.

Structural fixedness

Structural fixedness is the tendency to see things as a whole and therewith we come to the term structural fixation (Boyd & Goldenberg, 2010). I don’t know who invented the term, I first find it in Horowitz (1999) but it must be older.

The nine-dot puzzle (

CQ5) is a good example of structural fixation. We don’t see nine dots, we see a square. We are fixated on the structure of the nine dots. And, to use Ehrenfels’ theory, we complete unfinished structured to finished structures (Wagemans, 2015).

If you were born before 1990 you might have heard of MacGuyver (see picture below, source in the reference list). And if you don’t him, MacGuyver was a TV-show in the same category of The A-team and Knightrider about a man called MacGuyver (duh). He was a master in overcoming functional and structural fixation! Look it up if you can, it was awesome.

Conclusions on a Moment of Insight

According to the Gestalt theory, we can only solve specific types of problems, insight problems, when we overcome a form of fixation. And then we get to this idea, this is the Moment of Insight, and this is the source of creativity.

What happened to the Gestalt theory?

This Gestalt theory on the moment of insight is around 100 years old. According to Wagemans (2015), the Gestalt theory received much critique, especially after WWII. And in psychology, the Gestalt theory is not a serious subdiscipline anymore.

This is firstly due to the lack of legacy. With WWII Gestalt theorists moved from Germany to the USA. In the USA they could perform research but didn’t have funding to train PhDs. Also, several leading Gestalt theorists died young. Thus, there were no people to continue the Gestalt research.

Secondly, maybe even more importantly, the Gestalt theorists didn’t manage to develop the theory in a way it could stand critique.

The common understanding psychologists now have on this Moment of Insight, is that it is not one defining moment. But this moment would better be described as more and smaller moments of insight that appear in a process of hard work and creation (Sawyer, 2012).

Also, these smaller moments of insight can be false in the sense that you might think you have THE idea, but when you elaborate on it or think about it, you realize you were wrong (Weisberg, 2006). That sounds familiar to me…

But as Wagemans (2015, p.18) says wisely:

‘Although it may be true that the Gestalt theorist failed to develop a complete and acceptable theory to account for the important phenomena they adduced, it is also true that no one else has either.’

How the Gestalt theory is alive and kicking!

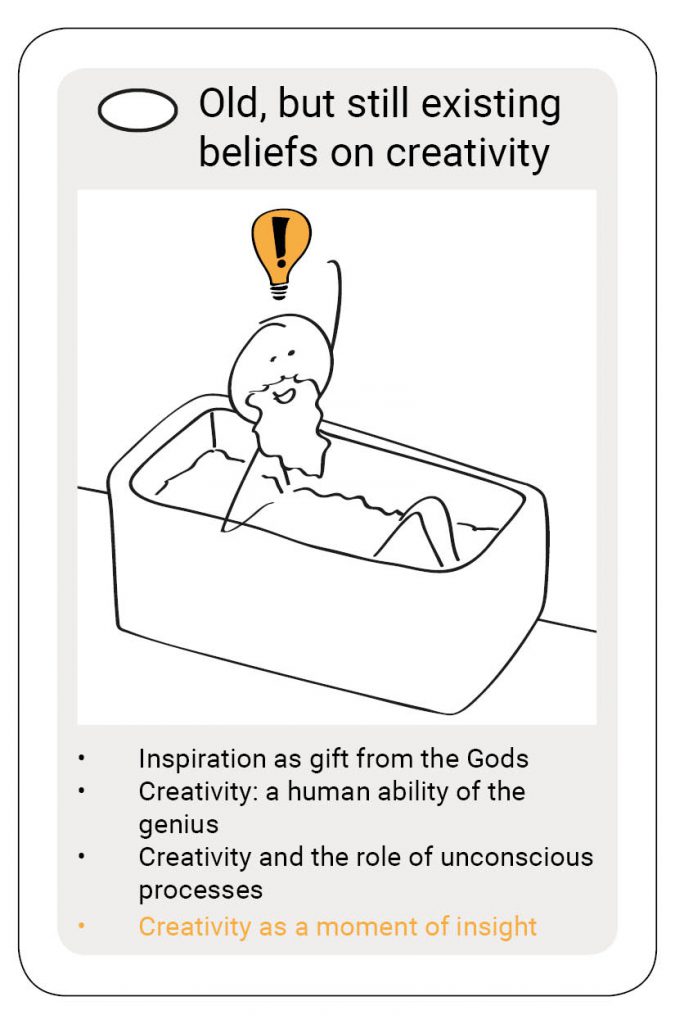

Even though Gestalt theory died with its main founders, elements of the theory are very much alive in our beliefs on creativity. I’ll give two examples.

The belief that expertise blocks creativity

If you have ever sat through a workshop in which you had to ‘be creative’ it could have meant: do not think of what you know, forget your expertise and just come up with wild ideas. That idea comes from the Gestalt theory.

In the Gestalt theory, experience is a negative thing when it comes to solving insight problems (Weisberg, 2006; Sawyer,2012). As Weisberg (2006, p.290) describes it:

‘Whereas experience and expertise have positive effects in the solution of many analytic problems […], applying one’s experience to an insight problem may result in an inability to restructure the situation in the way that is necessary for a solution.’

True or false?

False. Expertise and experience are of vital importance for creativity. There is extensive research that supports that claim (Weisberg, 2006; Sawyer, 2012; Ericsson & Lehmann, 2011).

Weisberg and Alba (1981a) performed famous research with the nine-dot puzzle. They hypothesized that if structural (or they called it functional, but I think it is more about the structure in this case) fixedness was overcome, participants would solve the problem. They used the nine-dot puzzle to test this. As the control group didn’t get a hint on how to solve the problem, the other group did get the hint to go outside the imaginary square to solve the problem.

However, these participants were not much better at solving the problem. Conclusion one: overcoming fixation is not a guarantee for solving the problem.

In a follow-up experiment (Weisberg & Alba 1981b), they had participants practice with other forms of dots and drawing lines between the dots moving outside the structure of the dots. And guess what, these people were better at solving the nine-dot problem. Conclusion two: experience contributes to overcoming fixation.

There is a lot more to tell about the role of expertise in creativity. This will return in the complex models on creativity in chapter four but also in the creativity debates described in the next chapter. For now, we can conclude that expertise contributes to creativity but many follow the Gestalt theory that expertise blocks creativity.

Restructuring forms the basis of important Design Theories

In the 1990s we see a revival of the Gestalt theory (Wagemans, 2015). Weisberg (2006) calls it the Neo-Gestalt theory that emphasized the importance of restructuring the representation of the problem (Kaplan & Simon, 1990; Ohlsson 1992). These concepts return often in influential design literature.

As I mentioned above, Weisberg and Alba (1981) found evidence, and there is more research that supports this conclusion (Weisberg, 2006). However, these insight problems are relatively simple and closed problems, they have one answer. Whereas design, and basically all complex problem solving of today are open problems. The concept of overcoming fixation and use restructuring might not be such a bad idea for these types of problems.

I’ll get to the relationship between creativity and Design Thinking in June (I can hardly wait) but as a teaser, I can say that foundations of Design Theory come from engineering perspectives on well, technical creation, and Neo-gestalt perspectives on problem-solving, it is all about perception and challenging your own assumptions (and restructuring).

And that wraps up chapter 2 of my creativity quartet 2020!

In this chapter, we looked at beliefs on creativity that have their foundations between 2500 and 100 years ago that still linger in the present and are thus important for the future. Pretty cool stuff, if I may say so myself. Here are the other cards from this chapter one more time.

What’s next?

Next chapter, we zoom into debates that are currently alive between creativity researchers. This is different from the subject list I published in the first article, but I am changing the list as I go along. It turns out I needed to restructure some topics :).

Thanks for reading and I wish you a pleasant continuation of your day.

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Boyd, D. and Goldenberg, J. (2013). Inside the box: Why the best business innovations are right in front of you. London, UK: PROFILE BOOKS LTD.

- Dorst, K. (2001). Creativity in the design process: co-evolution of problem-solution. Design Studies 22(5) pp 425-437.

- Ericsson, K., A, and Lehmann, A. C., (2011) “Expertise”, in Encyclopedia of Creativity: Second Edition, eds. Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R., London, UK: Academic Press, 2011, Vol 1. pp. 488-496.

- Kaplan, C. A., and Simon, H. A. (1990). In search of insight. Cognitive Psychology, 22, 374-419.

- Ohlsson, S. (1992). Information-processing explanations of insight and related phenomena. In Keane M. T. and Gilhooly K. J. (Eds). , Advances in the psychology of thinking (Vol. 1. pp. 1-44). New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wagemans, J. (2015). Historical and conceptual background: Gestalt theory. In: Oxford Handbook of Perceptual Organization, Ed. Wagemans J. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

- Weisberg, R. W., & Alba, .I. W. (1981a). An examination of the alleged role of “fixation” in the solution of several “insight” problems. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 110, 169-192.

- Weisberg, R. W., & Alba, J. W. (1981b). Gestalt theory, insight and past experience: Reply to Dominowski. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 110, 193-198.,

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Wertheimer, M. (1982). Productive Thinking. Chicago: Univ of Chicago.

Picture MacGuyver from https://www.realstylenetwork.com/celebrities/2016/02/macgyver-could-be-returning-to-tv-this-fall/. Retrieved 13th March 2020.

Do you know that feeling? That feeling that you found it, that final piece of the puzzle. That puzzle piece that makes everything fall into place. That feeling of completion and illumination. Do you?

Do you know that feeling? That feeling that you found it, that final piece of the puzzle. That puzzle piece that makes everything fall into place. That feeling of completion and illumination. Do you?