CQ18: Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, Verification

You know that feeling when you finish a book, close the cover, hold it in front of you, and you think: ‘WOW!’? I had that with the Art of Thought from Graham Wallas (1926/2014). But not for the obvious reasons that this book gave me a completely new insight on creativity. It is all the other stuff that is inspiring. Wallas was an educationalist and social psychologist with visionary ideas on education. I needed to remind myself constantly that this book is almost a hundred years old, especially for the third part of the book in which he discusses how to educate the Art of Thought.

You know that feeling when you finish a book, close the cover, hold it in front of you, and you think: ‘WOW!’? I had that with the Art of Thought from Graham Wallas (1926/2014). But not for the obvious reasons that this book gave me a completely new insight on creativity. It is all the other stuff that is inspiring. Wallas was an educationalist and social psychologist with visionary ideas on education. I needed to remind myself constantly that this book is almost a hundred years old, especially for the third part of the book in which he discusses how to educate the Art of Thought.

I keep picturing this city with smoke and factories, blacked faces from the mine work, children sitting in a classroom with a strict teacher in front of them. I see Wallas fighting in the frontline against this way of teaching. I wish that Wallas was alive and that I could hear his opinion about creativity and education nowadays…

In 2014 Graham Wallas’ Art of Thought (1926) was republished (see figure 1). This book cost around 25 euro and fits through a mailbox, which is handy in corona-times. Maybe a good present for your next birthday? That was my sales pitch, back to the content.

Why starting with Wallas?

I remember Wallas from my design literature as a student. He was the first name I recognized when I started reading creativity literature (mostly in the field of psychology). He is the starting point in any description of ‘the creative process’. Open any serious book on creativity, from psychology to design, and you will find Wallas in the reference list. His influence on creativity research is still huge. Yes, I dare to use this power word.

Wallas’ influence is showcased in Glăveanu (2019). Editor Vlad Glăveanu was able to get source texts from scholars/thinkers from before 1950, that influenced creativity research significantly. And he had contemporary creativity researchers reflect on these ‘older’ sources. Guess what? Wallas is the first chapter! Interestingly, it is Amabile reflects on his book, but that is for next week.

I think that many creativity practitioners also know this ‘creative process’. But maybe not everyone knows it comes from Wallas (1926). Does Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, Verification ring any bells? If not, don’t worry, I’ll explain it in this article. By the way, Wallas uses the word creative only twice in his explanation of the association process. He doesn’t call these stages the ‘creative process’. I guess the word wasn’t so popular yet in 1926 as it is almost a hundred years. I will keep putting the ‘creative process’ between quotation marks for this reason. But also for the reason, as I explained in CQ16, that I think we should call this process something like a ‘thinking process for creative output’, not a ‘creative process’.

This introduction is already too long, let’s start. Oh, wait, one more thing.

The title of the book is The Art of Thought and not something like ‘The Stages of a Creative Process’. That is a hint that the book is not only about the four stages of the ‘creative process’ but about, well as the title already says, about How to Think. Only a small part of the book dedicated to this process.

In this article, I will follow the structure of his book The Art of Thought. See the cover of the book in figure 1.

Figure 1: Cover of The Art of Thought, Graham Wallas (1926), re-print from 2014

12 chapters, 3 sections

The book exists out of 12 chapters that I think can be divided into three sections:

- ‘What is the Art of thought?’

- ‘How is the Art of Thought’ influenced?

- ‘How to nurture and develop the Art of Thought?’

I will discuss the first section the most extensively since that leads to the four stages of the ‘creative process’. I’ll be short on the second section and I will do a lot of quoting on the third section.

What is the Art of Thought?

Wallas does not give a specific definition of The Art of Thought. In chapters one and two he gives his opinion on Thinking, with a capital T, and emphasizes that we are humans and not machines. He focusses on the ‘human organism’ in chapter one and ‘human consciousness’ in chapter 2. These two concepts are important because they are the starting point to describe thinking. As Wallas puts it:

‘the conception of human organism and human consciousness best indicates the general facts with which such an art must deal…’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.37). And ‘such an art’ refers to Thinking.

He doesn’t like the popular metaphor of humans as machines. I guess he would also disagree with the computer metaphor some use nowadays. He sees the human being as an organism and a system of living elements (amen to that!). According to Wallas:

“the aim of the art of thought is an improved co-ordination of these elements in the process of thought” (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.vi).

Types of consciousnesses

Both conscious and unconscious play a big role in Wallas’ ideas on Thinking. According to Wallas consciousness and unconsciousness is not a matter of black and white. It is a grey-scale. He also uses words like subconscious and fringe-conscious (I’ll get to that).

Then there is also quasi-consciousness, the sort of consciousness you might experience when you are pretty drunk. And dissociated consciousness or co-consciousness, the sort of consciousness that a person might experience during hypnoses: being conscious and unconsciousness at the same time.

In the context of his ideas on the creative process, it is important to mention that according to Wallas, ‘free association’, happens in the unconsciousness. To exercise the Art of Thought, one should not only observe his (we are talking 1926, so, unfortunately, no ‘her’) consciousness but you should also learn to tap into your unconsciousness and observe it better.

Chapter three is about “the ‘natural’ thought-process which such an art must attempt to modify” (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.37).

To make case for his idea about this natural thought-process, he introduces two men whose theories form the basis of Wallas’ association process (=the creative process as we call in it nowadays). The first is Varendonck, a Belgian scholar who wrote ‘The Psychology of Day-Dreams’ (1921). The second is Poincaré, French philosopher/mathematician who wrote ‘Science and Method’ (1914), also see CQ10. Varendonck analyzed his thinking before, during, and after day-dreams. Poincaré kept a diary in which he wrote down how he came up with ideas for mathematical solutions.

Without using complex definitions, the most important take-away for Wallas is that both Varendonck and Poincaré support the idea of finding new associations in a more unconscious state. And the Art of Thought is the art to modify this process, which he refers to as the ‘natural’ thought process.

Chapters one to three lead to chapter four: the ‘Stages of Control’. Here come the famous four stages that are so familiar to us.

Chapter 4: Stages of Control

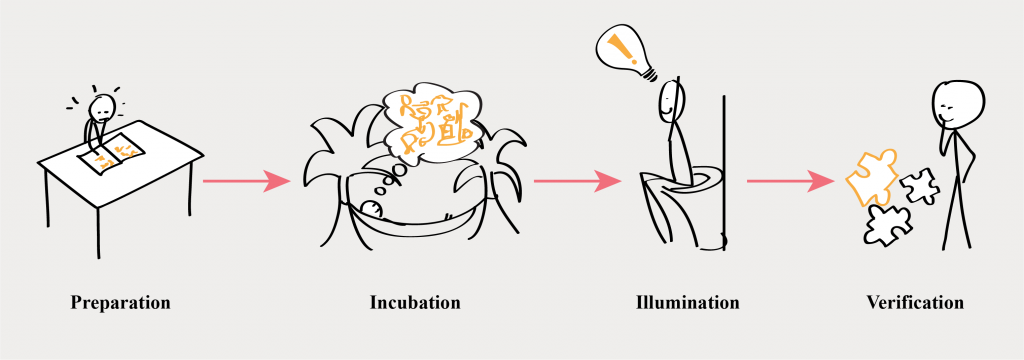

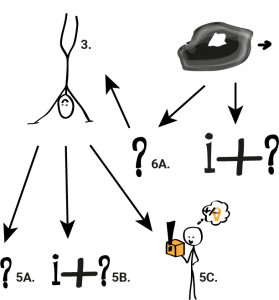

In short, in the Preparation-stage you consciously work on a problem. In the Incubation-stage only the subconscious somehow works on the problem. Then a solution comes to the conscious, that moment is accompanied by the feeling of Illumination. And that solution needs to be verified, does the solution you came up with truly solve the problem, hence Verification. See figure 2 for the four stages of control.

Figure 2: Stages of Control, based on Wallas (1926/2014)

To get to these four stages Wallas is inspired by Von Helmholtz (1821-1894), a German physician and physicist, descriptions about how new thoughts arrived to him. And he justifies these stages with examples from Varendonck and Poincaré. Let’s see what Wallas writes about these four stages.

Preparation and verification

Preparation is the ‘whole process of intellectual education’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.39). The processes of preparation and the process of verification are similar (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.39). Wallas decides not to elaborate further on these stages because they are clear as can be. The art of thought lies in modifying natural thinking that happens in Incubation and Illumination.

Incubation

According to Wallas (1926/2014) incubation has a negative and positive connotation. The negative is that you cannot consciously think about the problem you are working on during incubation. The positive is that you make a lot of new associations during incubation while you are not aware of it. Wallas focusses on the second, the positive side, of incubation.

Wallas explains that incubation can take two forms: thinking about another problem or relaxing. He favors the first because of its efficiency. And he advises us to work on multiple problems simultaneously. However, this is not the case ‘of the more difficult forms of creative thought, the making, for instance, of a scientific discovery, or the writing of a poem or play or the formulation of an important political decision’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.42). In that case, relaxation is the better strategy because you want nothing to interfere with the unconscious to do its work.

I guess the complex problems we are working on today, all fall into the more ‘difficult forms of creative thought’-category, thus relaxation is the way to go. That relaxation helps to make new connections within your brain is supported by neuroscience (Dietrich, 2004; Carson, 2010).

From incubation to illumination

If we want to modify our natural thought process we need illumination to be more than a flash of insight. ‘If we so define the Illumination stage as to restricted to this instantaneous ‘flash’ it is obvious that we cannot influence it by a direct effort of will; because we can only bring our will to bear upon psychological events which last for an appreciable time. (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.46)

And:

‘If our will is to control a psychological process, it is necessary that the process should not only last for an appreciable time, but should also be, during that time, sufficiently conscious for the thinker to be at least aware that something is happening to him.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.47)

Interestingly, Wallas mentions a fifth stage: Intimation. Intimation is the ‘tip of the tongue feeling’. It is the feeling you almost know the answer. It happens not in your subconsciousness and not in your consciousness but in your ‘fringe-consciousness’ as he calls it, which means somewhere in between. Intimation is the stage when incubation almost comes to the surface and leads to illumination. To quote Wallas again:

‘I find it convenient to use the term ‘Intimation’ for that moment in the Illumination stage when our fringe-consciousness of an association-train is in the state of rising consciousness which indicated that the fully conscious flash of success is coming’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.48).

I have this feeling of intimation almost ten years…

So there you have it. The stages of control. The foundation of many theories on ‘creative processes’. Something these stages of control are even referred to as THE creative process. However, this process we are talking about is only one chapter, 18 pages of a book on Thought, not even on creativity. Yet this book forms a big part of the foundation of our believes how creativity works as a process. I don’t think Wallas could have ever thought that this would be his legacy.

I could leave it here. But as practitioners, you should know about the rest of the book. Before I get to the second and the third part, please keep the following in mind:

- Wallas NEVER refers to the stages of control as the creative process. Though he does imply that creative thinkers have mastered the Art of Thought and that they are good at this association process.

- The stages of control are based on three ‘theories’ that are both based on self-assessment. You can ask yourself how scientifically sound that is.

- Wallas refers to a fifth stage, Intimation, quite important but I guess not important enough according to scholars using his theory because somewhere along the way intimation got lost in citing Wallas.

How is the Art of Thought influenced?

In the second part of the book, chapter 5 to 9, Wallas gives body to his theory on the Art of Thought. Wallas writes about influences of emotion on Thought, the (dis)advantages of habits on Thought, the role of effort and energy on Thought, and different types of Thought. The latter is mainly about the influence of culture (ex. Englishmen think differently than Frenchmen because of their cultural background).

The ‘different levels of consciousness’ and ‘natural associations to improve thinking’ return in each of these chapters. Sometimes he refers to one of the stages of control. When he refers to these stages it is to incubation and intimation.

I hope you recognize that all these influences (emotion, effort, culture, etc.) on Thinking are also part of contemporary research on creativity. These influences on Thinking return in my chapters on creativity mindsets and skills.

Now get to the part of the book that synchronized most with my passion. The third section of the book is on nurturing and developing the Art of Thought.

How to nurture and develop the Art of Thought?

I might go a little off course in my elaboration on this third section. However, if you are a creativity professional, trainer, leader, or facilitator, knowledge about teaching brings us super relevant insights. I like to remind you again that this book is almost a hundred years old. Like I said in the introduction, Wallas was also an educationist and he had a clear vision of education. His vision is very valid anno 2020.

I going to quote a lot of texts because he chose his words better then I could paraphrase them.

The thinker at school

Chapter 10, about ‘the thinker at school’, is the starting point for his oration on education.

‘I shall discuss the art of education as a section of the art of thought, that is to say, I shall ask how far a teacher can hope to increase the future output of creative thought by those thinkers who as students pass through his hands. For that purpose it will be best to start with a mental picture, not of an educational system or a series of statistical curves, but of some supernormal hum being who has actually added to the intellectual heritage of mankind.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.131).

I like that: the art of education. To translate this quote to the year 2020: forget spreadsheets. Look first at how great thinkers were educated, and learn from that. Wallas takes Plato as an example. He pictures Plato in Ancient Greece, where Plato grew up, what did during the day, and how he was educated. As a little boy, Plato used to play naked in the sun, and when he was old enough he went to the gymnasium. In summers he explored the outside and all the richness of nature and culture in Ancient Greece, including Socrates:

“And one day, after his public admission as a citizen, he was free to sit with shining eyes at the feet of Socrates in a corner of the Agora, to argue with friends during walks up the Ilyssus Valley as to nature of man and God and The State, or to stay up for half the night writing the stilted love-poems and discourses at which in later years he would laugh; and so, after many travels, and with no clear division between his life as student, and teacher, and statesman, he became the most influential thinker in all history.” (Wallas, 1926/2014: pp.132-133).

Yes, that is one sentence. And doesn’t it sound romantic?

How to teach when there is so much information?

Wallas pictures Plato in his time.

‘If Plato were born to-day[….]he would probably live in one of the meanly uniform houses of a city street, and be the child of parents with few traditions of culture. Nothing in his daily surroundings would stimulate in him the passion of truth and beauty which the Athenian temples and porticoes, and the eager talkers and traders and poets and orators, and the valleys and hills and the coast of Attica stimulated in the earlier Plato. […] Most of that which Plato of Athens learnt at first hand from nature and mankind, Plato of London or New York must learn, if at all, at second hand, from books and machines.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.133).

And in the next sentence comes the prophecy:

‘The great industrial nations may perhaps in the next hundred years rebuild their cities, and scatter electrically-driven industries over the country-side. But, for good or evil, we shall never return to the ‘natural’ short-range environment of Plato’s Athens.” (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.133).

Oh oh, the relevance!

Wallas points out the amount of information Plato is exposed to is so much littler than the amount of information Wallas himself is exposed to in 1926. Wallas sees no other way than learning something must come from second hand. If we extrapolate this to 2020, we are learning from the tenth hand.

Then Wallas questions himself, how could we help a child like Plato learn second hand in 1926? Wallas does not believe in leaving it all to the child’s curiosity;

it ‘shows that the best way to do things is not the way which is most likely to occur to one unaided mind” p. For example, if a child shows no interest in reading, should he not learn to read anyway?’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.134).

But…

‘If, however, we accept responsibility for showing a child what we believe is the best way to develop his power of thought, we must try ourselves to be clear on what we mean by ‘best’. Teaching is to ‘compromise between the powers and needs of the child and those of the future adult.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.135).

‘One of the most difficult elements in this compromise is the question how far and at what age the teacher should aim at teaching the pupil to stimulate his mental energy by conscious and voluntary effort; and how far mental energy should be left to grow out of the pupil’s own spontaneous ‘urge’.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.136)

The role of examination

Wallas also discusses examination.

‘The examination system, as practised in England, has many obvious dangers; examination-passing is apt to become an end in itself, both for teacher and for student; and the nervous strain which follows from the realization that the opportunities of one’s whole future life may depend on the effort of a few days is often harmful.’ (Wallas, 1926/2014: p.137).

He also sees the advantage that this examination might be the first time the student is pushed to give an effort. Finally, Wallas discusses the importance of leisure at school because it will give the students the incubation time they need to come to illumination.

Chapter 11: the education system

In chapter 11 he discusses the public education system (in England). He makes an argument for education in England to stimulate smart kids. And that it is more difficult for an English child of working-class origin to become a creative thinker than for a child of middle-class origin. Simply because their immediate surroundings do not stimulate the child:

‘The ordinary working-class home contains few books, and is too crowded and noisy for much leisure and day-dreaming. The father spends the day in sever manual labour, is too tired in the evening to answer the questions of a clever child, and has little intellectual experience of his own; the mother either goes out to work or spends the day in the housework.’(Wallas, 1926/2014: p.154).

He discusses until what minimum age children should attend school and the probability of political parties voting in favor or against the increase from fourteen to sixteen. He thinks this will happen soon and history shows he was right.

Chapter 12: Role of the teacher

In chapter 12 he discusses the role of a teacher and whether a teacher should be a content expert/practitioner or a teaching expert. For example, in learning to paint, should the teacher be a good painter himself?

He likes the idea of teachers who hold sabbaticals in which they return to practice. Or teachers that are part-time practitioners. He explains the pro’s and con’s of teachers that are good at teaching but have no practical experience, and of teachers with a lot of practical experience but lack good teaching skills. A good mix would be the solution.

Conclusions: be a human, not a robot

I’m no educationalist, nor pedagogue. But it seems to me that the discussions Wallas brings forward are as relevant today as they were a hundred years ago. You sort of wonder why we, ‘the smart adults’, the ones creating the education system, hold on to some teaching methods that were maybe already outdated almost one hundred years ago…

I think the Art of Thought is a call for humans to create and think as human beings, in a natural environment, instead of as machines. It’s a call for allowing ourselves and our children, being led by curiosity, like Plato in that garden. I love this view on thinking and implicitly on creativity. In my view, to be creative is to develop oneself as a human being, to be resourceful, to be resilient, to survive.

But remember, this is my interpretation of this book. We’ll see next week how Teresa Amabile interpreted Wallas. If you want the ‘truth’ you are going to have to read it yourself. I advise you to do so.

You will also find the cards for the next weeks and my references below. Thanks for reading and I wish you a pleasant continuation of your day.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Carson, S. (2010). Your Creative Brain: Seven Steps to Maximize Imagination, Productivity, and

Innovation in Your Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. - Dietrich (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 11(6), pp. 1101-1026.

- Glăveanu, V. P. (ed.) (2019). The Creativity Reader. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wallas, G. (1926). Art of Thought. Kent: Solis press, re-print 2014.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ4: No.1 WRONG assumption on Creativity

In the previous two articles, I explained the Western social and economic landscape in which creativity had a chance to become a valuable ability. Thi

CQ23: Creative Problem Solving, the ins and outs

As the term implies, CPS is a method to train people on how to enhance their creativity and become more ‘creative’ problems-solver. I am positive that

CQ21: How do people solve problems?

The Cognitive Analytical Model (CAM) is described by Robert W. Weisberg in his 2006 book: Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Sci

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.