CQ13: Could Einstein paint like Picasso?

Could Einstein paint like Picasso? No. And Picasso was no brainiac like Einstein was. We give both men credit for their great creative contributions, in their field, in their domain. The question that will entertain us in this article is: Is creativity a domain-specific ability or is creativity a general ability, or something in between?

Could Einstein paint like Picasso? No. And Picasso was no brainiac like Einstein was. We give both men credit for their great creative contributions, in their field, in their domain. The question that will entertain us in this article is: Is creativity a domain-specific ability or is creativity a general ability, or something in between?

I’ll run you through five options.

Option 1: Creative thinking is a general human ability, that is independent of domain-specific abilities

The idea that creativity is a general human ability took serious forms when Guilford entered the stage in 1950. Remember Joy Paul Guilford? If not, see CQ4.

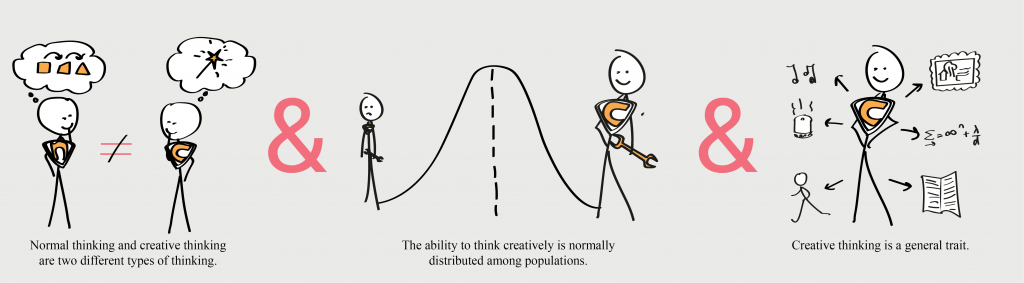

Guilford was a psychometrist. That means he was specialized in measuring psychological phenomenons. When it comes to creative thinking (read creativity) Guilford made some assumptions (see also figure below):

- creative thinking exists (Guilford, 1950) and is therewith different from normal thinking. That means creative thinking cannot be measured through intelligence tests (Guilford, 1950);

- because creative thinking is a human ability, creative thinking, is same as intelligence, normally distributed;

- Guilford implicitly assumed that creative thinking is a general ability, like intelligence, also because he compared creative thinking with intelligence (Plucker, 1998).

(If you have a tip on how to get the text in this picture sharper, please tell me)

As I explained in CQ4, Guilford argued that creative thinking existed out of divergent thinking (the ability to come up with options) and convergent thinking (the ability to judge options).

Can we say that Guilford’s assumptions were correct and that creativity is a general human ability, domain-independent? In order to answer that question, we need to dive a little deeper into how Guilford measured creative thinking.

Divergent thinking tests

I already mentioned them in CQ4, divergent thinking tests. Guilford designed divergent thinking tests in the first place to measure creative potential, especially in children. After Guilford’s divergent thinking tests many divergent thinking tests followed. The most famous, and still widely used divergent thinking test is the Torrance Test of Creative Thinking (TTCT) (Plucker, 1998, Sawyer, 2012 p.48). I’ll elaborate on this test because it gives us more information.

The Torrance Test of Creative Thinking

The TTCT was created by Ellis Paul Torrance (1915-2003) who based his test on Guilford’s model of divergent thinking. The tests measure fluency, flexibility, originality, and elaboration through verbal and figural assignments. For example, there are verbal questions in which you have to think up as many ways how to use this brick. And figural questions in which you have to complete pictures. Torrance primarily designed to find the creative geniuses amongst children, so that they could be supported to live up their creative potential (Sawyer, 2012: p.48) (and to beat the Russians, and make America great again, of course).

Critique on divergent thinking tests

In science, when you measure something, you need to argue the validity and reliability of your empirical research. Validity is about measuring what you say you are measuring. In this case, does a divergent thinking test measure divergent thinking? And reliability says something about the consistency of the result. If you would do the same research in the same way again would you get the same result?

Divergent thinking tests have been extensively evaluated on validity and reliability (Runco, 2010) because there is a lot of data available on them. Especially on the TTCT. The TTCT has been used in more than 2000 studies and is translated in over 32 languages (Saywer, 2012: p. 48)!

Psychologists have done complex statistical analyses with these numbers. And here comes the great disappointments I recognize from friends who pursued a scientific career: you run the number this way, you get answer black, you run the number that way, you get answer white. It is all data manipulation.

Same goes for the reliability and validity of divergent thinking tests, psychologists that argue that these tests are not reliable and valid will find support in the numbers and vice versa. Psychologists compared results from divergent thinking tests with results from tests in which participants had to showcase their creativity (=creative performance). Most studies show a low correlation between divergent thinking tests and creative performance.

What I find interesting is that I cannot find any other way psychometrists measure creative thinking expect these divergent thinking tests. No wonder also scientists use these words interchangeably.

Conclusion for option 1: probably untrue

Overall psychologists nowadays believe that creativity cannot be measured only through divergent thinking tests. In fact, maybe only a small part of creativity is due to divergent thinking (Beghetto, 2004, Saywer, 2012). And so that option one: creativity is a general human ability independent of the domain is believed to be untrue.

Of course, we can disagree with this belief and I’ll get to that later. First, let’s have a look at option 2.

Option 2: Creative performance is mostly dependent on domain-specific abilities

What is a ‘domain’?

According to Sawyer (2012, p.59)

‘Psychologists intend to define a domain […] in terms of the mental activities that underlie expertise in the domain. […]. A domain involves internal, symbolic language representations; and operations of those representations’.

Distinguishing domains

Psychologists have tried to distinguish domains in multiple ways. Maybe the most famous is Gardner’s (1983) theory of multiple intelligences. He defined eight types of intelligence and provides us famous examples as well (Weisberg, 2006, p. 78,80):

- Spatial (Picasso)

- Linguistic (T.S. Eliot, English writer)

- Logical-mathematical (Albert Einstein)

- Bodily-Kinesthetic (Martha Graham, American dancer, and choreographer)

- Musical (Igor Stravinsky)

- Interpersonal, ‘able to achieve the high ability to understanding or of relating to others’ (Mahatma Gandhi)

- Intrapersonal ‘able to achieve a high level of self-understanding’ (Sigmund Freud)

- Naturalistic ‘ able to discern patterns or regularities in natural environments (Charles Darwin)

Another view is that of Kaufman and Baer (2004), in their research they came to nine domains that could be clustered in three groups:

- Empathy/communication (interpersonal relationships, communication, solving personal problems, writing)

- Hands-on creativity (arts, crafts, bodily/physical)

- Math/science creativity (math, science)

There are more of these domain distinctions for example by Carson (2005) and Holland (1997). All these domain distinctions have in common that the domains are defined broadly, not specific (Sawyer, 2012, p60). I’ll get back to that.

Domain-specific abilities

Domain-specific are abilities that are specific for a certain domain, duh! Think of the ability and technique you need to paint, the knowledge of math for a mathematician, muscles and technique to perform a certain dance, etc.

A case for domain-specific creativity

When we look for evidence in theory for domain specificity approach of creativity, we have to look at research from John Baer. And lucky for you, he even has a youtube video in which he explains his findings. Check it out here.

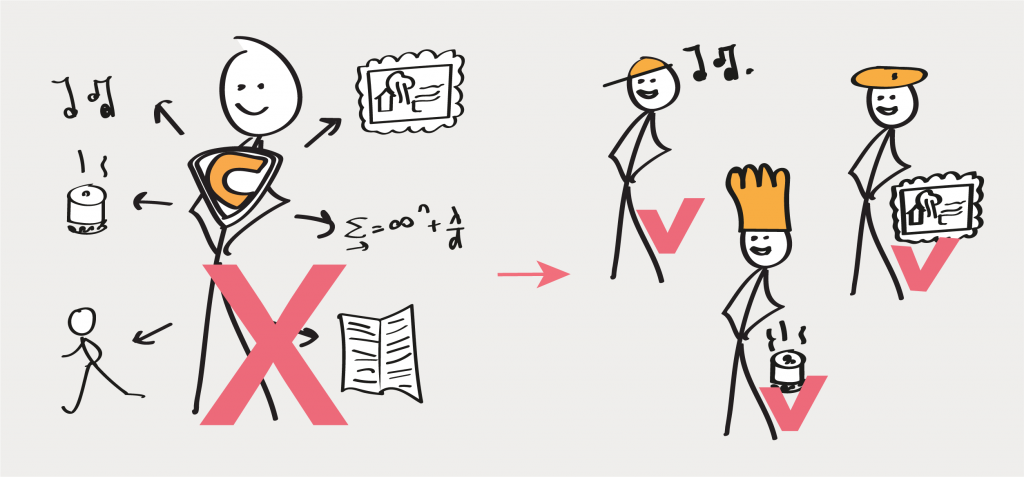

Baer (1993) measured creative performances by experts assessing the creativeness (level of creativity) of the outcomes of participants in different domains, and within the same domain. Participants had to do poetry writing, oral and written storytelling, solving mathematical puzzles and create collages. He found a low correlation of creative output between these four activities. And so he concluded that creativity (read creative performance) is a domain-specific ability (see figure below). And maybe it’s even more specific.

Microdomains

Like I stated above, efforts for domain distinctions remain broad. Baer (1993) found no significant correlation between creative performance in poetry writing and oral and written storytelling. While both activities are part of the same domain (linguistic). Karmiloff-Smith (1992) called these smaller domains within domains microdomains, and activities in them are called task-specific instead of domain-specific (Baer, 1998).

Conclusion for option 2: seems at least partly true

If you simply use common sense you come to the conclusion that creative performance is at least partly a result of domain-specific abilities. Of course, you have to be able to sing on key if you want to sing like Pavarotti.

Psychologists come to the same conclusion. As stated above, over twenty-five years ago Baer made a case to view creativity as a domain-specific ability and not as a general ability like intelligence (Baer, 1993)*. And since there have been some serious problems with the validity of divergent thinking tests, most psychologists believe that there is at least a part of the creative performance due to domain-specific abilities (Saywer, 2012: p.60).

*Baer 1993 is a reference to an empirical research article. In the previous article, I argued that these articles are not convenient to get much information from because one study is just one study. In this case, Baer has done much more research on this matter and he is not the only one. This study from 1993 is most cited and always referred to in my overview books from Weisberg (2006) and Sawyer (2012) and part of the Encyclopedia of Creativity (2011). Thus, it is not ‘just a reference to an empirical study’, just to let you know…

Here is what’s strange

The view that creativity (creative performance) is at least partly domain-specific does not oppose the view that creativity (the potential to think creatively) is a general human trait.

According to Plucker (1998), the critique on divergent thinking tests is invalid. Divergent thinking tests were never designed to measure creative performance. They meant to measure creative potential. Guilford and Torrance assumed that the potential to think creatively was a general human ability, like intelligence. But they don’t tell us how this potential is related to creative performance. If Plucker runs the numbers there is a correlation between creative potential and creative performance (Plucker, 1998). Just like Baer, Plucker also gives his opinion on youtube. Find his video here. Plucker and Baer are happy to agree they disagree as Plucker thanks Baer in his article from 1998 and vice versa.

I think this is a great example of miscommunication. If we say ‘creativity’ to ‘creative thinking’, to ‘creative thinking potential’, to ‘creative potential’ and to ‘creative performance’, we use one word to say four different things. So honestly, we can’t draw any solid conclusion here. This issue will return in the next article on the definitions of creativity CQ14.

To help us on the way, I have two in-between views to discuss. The horizontal and the vertical view (my words). Then there is the fifth option which is the most extreme option. I’ll finish the article with some simple questions that have difficult answers.

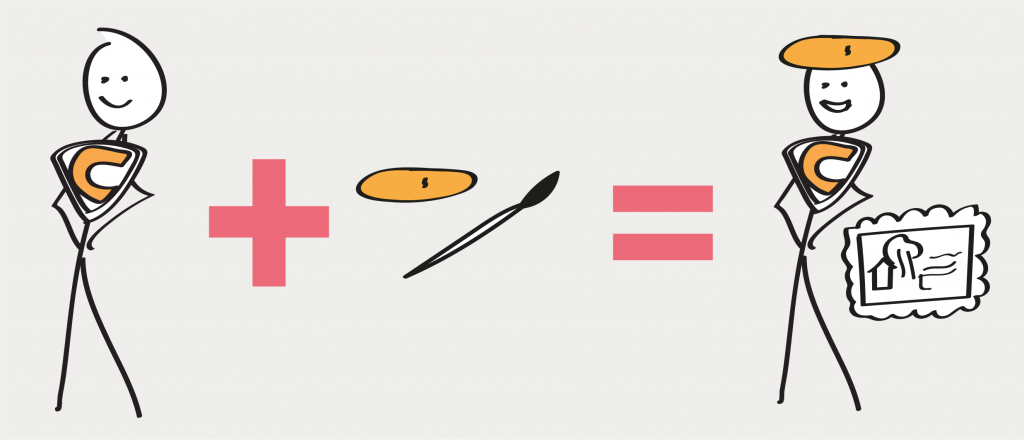

Option 3: creativity is general creativity skills + domain-specific skills

This is the horizontal view. With that, I mean that the creative skills and the domain skills are on the same level (see figure below). This view is part of Teresa Amabile’s theory of creativity. According to Amabile, creative performance is a combination of creative thinking skills, domain-specific abilities, and motivation (Amabile, 1998). Teresa was one of the first to include the context in creativity research. And she created a new way of measuring creativity that is now often used. I will devote an entire article to her model of creativity in the next chapter because her line of thinking is influential both in theory and business.

Conclusion for option 3: could be true

Amabile is one of the leaders when it comes to creativity research. Her line of thinking has many followers. To put the two options together is a convenient way to stay out of trouble in this matter.

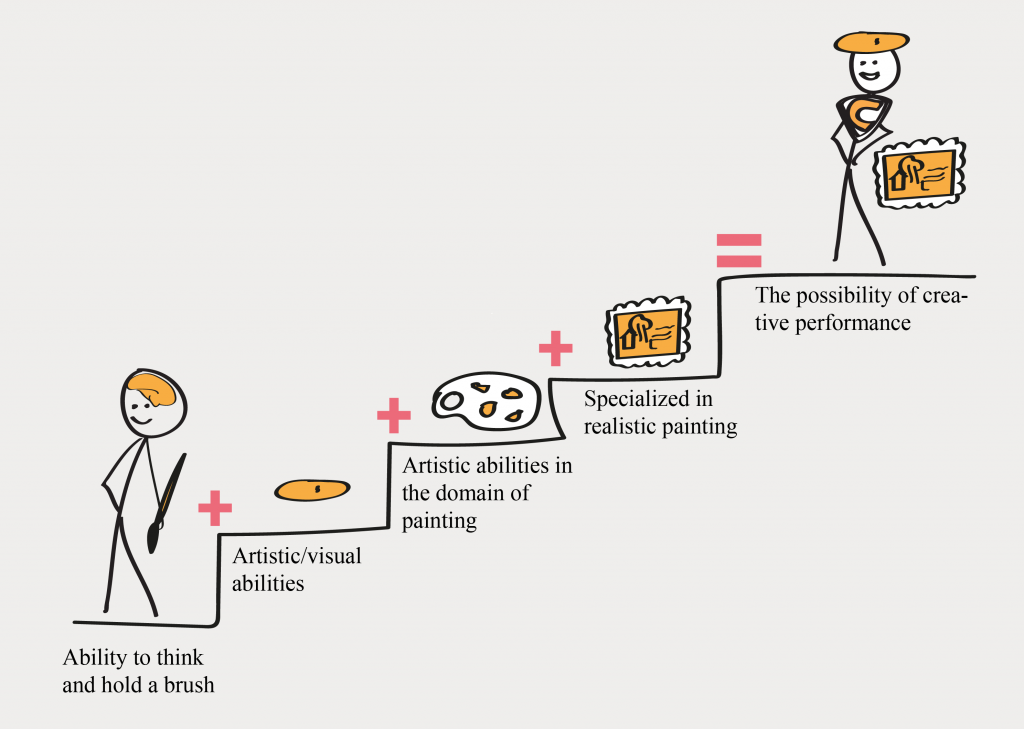

Option 4: the APT model

Baer brought some nuance to his domain-specific ability theory on creativity. Together with James Kaufman (also a creativity research guru), he created the APT model (Baer and Kaufman, 2005), see figure below. The ‘APT model is a hierarchical theory of creativity that included both domain-general and domain-specific elements. The central idea of the hierarchical model is that there are varying degrees of domain specificity and generality ranging from the most general intelligence […] to the most specific (e.g. microdomains or task specificity)’ (Baer, 2011: p.407). Where APT is an abbreviation for Amusement Park Theoretical (Baer and Kaufman, 2005). It’s a metaphor…

In my words, this is the vertical view because of the hierarchy in the model. We have four levels (Baer, 2011: p.407):

‘Initial requirements are completely domain-general factors that influence creative performance’, like intelligence and I think also the ability to hold a paintbrush in a way you can use it.

‘General thematic areas are broadly defined fields or areas that include many related domains’. The authors defined seven of those areas that are necessary for creativity (Baer, 2011: p.407):

- ‘Performance

- Math/science

- Problem-solving

- Artistic/visual

- Artistic/verbal

- Interpersonal

- Entrepreneur’

Then we have domains.

‘Domains lie within larger General Thematic Areas and refer to a more limited range of creative activities’ (Baer, 2011: p.407). For example in the Artistic/visual theme, we have a painter and a filmmaker and a photoshop artist.

‘Microdomains refer to more specific tasks within domains’ (Baer, 2011: p.407). So in our example of the painting, we have an impressionist a surrealist and a realist, and they all use a different type of paint.

In the APT-model there is room for general skills and for divergent thinking. However, according to Baer (2011), there are different types of divergent thinking skills. And we should take this into account when we train creativity.

Conclusion for option 4: could be true, but leaves me with questions

Baer ends his overview of research on this topic with: ‘

It should be noted that the research evidence pointing toward domain specificity o creativity is fairly new, and, like the research that preceded it, this research may not tell the whole story’ (Baer, 2011: p.408).

I have no further scientific argumentation in favor of or against this model. I do have some questions:

One, where do you draw the line between these four levels? It seems more like a greyscale to me. Related to this I wonder at what level you can develop expertise. Or is developing expertise moving on to this hierarchical ladder? That seems like a good comparison to me. I have no theory to support or reject this idea.

Two, what is the difference in how these levels operate within us? Or do they operate in the same way? If I want to develop these particular levels in others, I need to know that.

Three, those general thematic areas are on the same level as Gardner’s domains (Baer and Kaufman, 2005), but the article doesn’t tell us how they came to these domains. That would be my main question: why these areas? And how is problem-solving on the same level as artistic/visual and math/science? And where do I fit in as a designer? Where does a policeman fit it, a teacher, an innovation manager, etc.?

I think the APT-model is a nice idea to but if you look at it from the perspective of developing expertise, it doesn’t bring us much new knowledge. Now we come to the fifth option, and I’m going to be short on this one.

Option 5: creativity is completely domain-specific because creative thinking doesn’t exist

Baer leaves room in his theory for the idea that creative thinking is part of creative performance. He argues that there are different types of divergent thinking (and this is what he refers to as creative thinking). Weisberg (2006) theorized that creative performance is due to domain-specific abilities and normal cognitive processes. There is no such thing as a special kind of thinking like creative thinking. I’ll leave the conclusion for this option open because I will devote an entire article to this idea in three weeks. Cliffhanger :).

Overall conclusion

The overall conclusion is that there is no conclusion, which is sort of the entire story of creativity research. But if we have to choose between domain-specific teaching creativity and general teaching creativity, I follow Baer’s argument (Baer, 1998) that we can better go for the domain-specific approach. If creativity is not domain-specific, no harm is done. But if it is, and we teach creativity in a general way, well we have been wasting a lot of time and money.

A way to execute this in practice is to follows Baer’s idea and train diverging through different domains. Where the TCTT is only verbal and figural (and many divergent exercises are also verbal or figural). We could also have people divergence on how they move (in the domain of dance/performance). It would be great to see some ties get in touch with there modern dance skills.

What’s next

Next week I am going to figure out the definition of creativity. I’m not looking forward to that one, but it is important, especially to overcome the miscommunication about creativity that is giving me feelings of frustration.

You will find the cards for the next weeks below.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, 76(5), pp. 76-87.

- Baer, J. (1993). Divergent thinking and creativity: A task-specific approach. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

- Baer, J. (1998). The Case for Domain Specificity of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 11(2), pp. 173-177.

- Baer, J. (2011). Domains of Creativity. In Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R. (Eds.). Encyclopedia of Creativity. Second Edition, Vol 1. pp. 404-408. London, UK: Academic Press.

- Baer, J. and Kaufman, J. C. (2005). Bridging generality and specificity: The Amusement Part Theoretical Model (APT) model of creativity. Roeper Review Vol. 27: pp. 158-163.

- Carson, S. H., Peterson, J. B., and Higgins, D. M. (2005). Reliability, validity, and factor structure of the Creative Achievement Questionnaire. Creativity Research Journal, 17(1), pp. 37-50.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), pp. 444-454.

- Holland J. L. (1997). Making vocational choices: A theory of vocational personalities and work environment. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- Karmiloff-Smith, A. (1992). Beyond modularity: A developmental perspective on cognitive science. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kaufman, J. C. and, Baer, J. (2004). Sure, I’m creative – but not in math! Self-reported creativity in diverse domains. Empirical Studies of the Arts, 22, pp.143-155.

- Plucker, J. A. (1998). Beware of Simple Conclusions: The Case for Content generality of Creativity. Creativity Research Journal, 11(2), pp. 179-182.

- Runco, M.A. (2010). Divergent Thinking, Creativity, and Ideation. In Kaufman J. C., and Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, pp. 413-446. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ7: History is awesome!

If you would tell me twenty years ago that I would say that history is awesome, I would have kept you for a fool. I was born in the 80s and I grew up

CQ17: Theoretical models on creativity, where to start?

There are as many theoretical models on creativity as models in the first episode of a new season of America’s Next Top Model. Fortunately, we have a

CQ3: ‘Creative industries’ should go

Last Summer I was at a creativity conference with the title: Dutch Creativity Festival, organized by the ‘ADCN: Club for Creativity’. I did not check

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.