CQ23: Creative Problem Solving, the ins and outs

As the term implies, CPS is a method to train people on how to enhance their creativity and become more ‘creative’ problems-solver.

As the term implies, CPS is a method to train people on how to enhance their creativity and become more ‘creative’ problems-solver.

I am positive that 99,9% of the professionals that had any training on creativity or that were asked to ‘be creative’ in a workshop, experienced CPS. The method forms the basis of any creativity professional. In fact, I think that most creativity professionals refer to CPS when they refer to ‘the creative process’.

In this article, I will start with a short description of the method and I’ll give the basic principles behind the method. I will elaborate on the history of CPS and on the people and organization(s) that founded CPS and remain to nurture it. There is much to tell in that respect.

In my article on brainstorming and CPS as a workshop technique, I will go into the details of CPS as a workshop technique.

I like to thank my dear colleagues, Katrina Heijne, Han van der Meer, and Sam Franklin, from the Delft University of Technology for their help in getting the facts straight on CPS. Thank you, your insights and materials were crucial for writing this piece!

CPS in a nutshell

Creative Problem Solving is a method to solve problems creatively, duh. It is the only method in this chapter that doesn’t have an engineering background, but a marketing and psychology background.

We could say that Alex Osborn (inventor of brainstorming) laid the foundations of CPS in his 1953 book: ‘Applied Imagination, principles and procedures of creative thinking’.

Over the years the CPS-method has gone through some changes, but three elements have ‘always’ been part of CPS.

First, the underlying assumption that everyone can be trained to become (more) creative. Second, three phases that return in every model of the CPS-method. Third, each phase exists out of two stages: a diverging and converging stage.

Everyone can be trained to become more creative

We can be short about this point. That we can be trained to become more creative was the credo of Alex Osborn. Without this assumption, his entire argument wouldn’t make sense. However, in the 1950s this point of view was not the common one. Many personality psychologists at that time believed that creativity was a fixed ability, like intelligence (Saywer, 2012). Of course, as a personality psychologist, that point of view is more appealing. We all see the world the way we want to…

Three phases

Over the years CPS has gone from 7 to 5 to 6 to 4 phases, and I will get to those later in this article. However, if we take a helicopter view we can summarize these phases into three phases: a problem phase, an idea generation phase, and a solution implementation phase.

Problem phase

In the problem phase, we try to understand the problem. In CPS-models we find words like ‘clarification’, ‘information finding’, ‘mess finding’, ‘fact-finding’, or ‘object finding’. We could say it is the analysis of the situation to determine the problem. In the words of Wallas (1926), we would say this is the ‘Preparation stage’ (CQ18).

Idea generation phase

In the idea generation phase, we try to come with the idea of which we think it could solve our problem. Idea generation is at the core of CPS. It is the place where we are supposed to deliberate come to a moment of insight. In terms of Wallas (1926) idea generation is a deliberate form of ‘incubation’ to come to ‘illumination’. Our attention is not on the problem but on the solution.

Solution implementation phase

This phase comes in different wordings ‘solution finding’ and ‘acceptance finding’. In Wallas’s words, this phase is about ‘verification’.

If we look at ten different CPS-models from Puccio, Murdock, and Mance (2007), the idea generation phase is the only phase that comes back as such in all CPS-models (Puccio & Cabra, 2009). What is remarkable that acceptance finding is often named as one of the last steps in a CPS-model. While in reality, acceptance finding starts with clarifying the problem, I’ll get to that later.

The third principle that returns in each CPS-model is the principle of diverging-converging.

The principle of diverging-converging

In common language, diverging is the activity of creating options, and converging is the activity of choosing options. This is how I often refer to the two stages. However, it is not exactly correct.

In ‘Applied Imagination’, Osborn never mentions the terms diverging and converging. Never. It was not Osborn who introduced these terms in the World of Creativity.

It was Guilford that made these words popular terms concerning creativity. However, according to Guilford, divergent thinking is more specific than the mere creation of options. Divergent thinking exists out of four elements (Guilford, 1968, see CQ16):

- Fluency (the number of ideas)

- Flexibility

- Originality

- Elaboration

The creation of options only refers to the first element: fluency. Fluency, generating as many ideas as you can, relates to one of Osborn’s brainstorm rules: ‘Quantity is wanted. The more ideas we pile up, the more likelihood of winners.’ (Osborn, 1948: p. 269).

We see that most techniques used to enhance creativity have the purpose to increase fluency or flexibility. By focusing on these elements we hope to achieve originality. And if we let people create a communication tool, like a poster, of the idea we focus on elaboration.

The separation of diverging and converging is based on Osborn’s first ground rule of brainstorming: ‘judicial judgment is ruled out: Criticism of ideas will be withheld until the next day’ (Osborn, 1948: p.269).

Converging, dictionary wise, is moving to one point. However, when we converge in CPS we evaluate and judge ideas and then choose the ideas we want to move forward with. However, Guilford doesn’t call this converging.

According to Guilford (1968), diverging and converging are both about producing information. In convergent thinking, one has to arrive at one right answer, wherein diverging thinking there is no one right answer, there can be multiple. To quote:

‘The information given generally is structured so that there is only one right answer’ (Guilford, p8). These stages diverging-converging should be if we follow Guilford (1968): diverging – evaluating. In evaluating the focus is on critical thinking and decision making. And we say that converging thinking is about critical thinking and decision making. See my point?

I ask myself, how did diverging-converging become part of CPS?

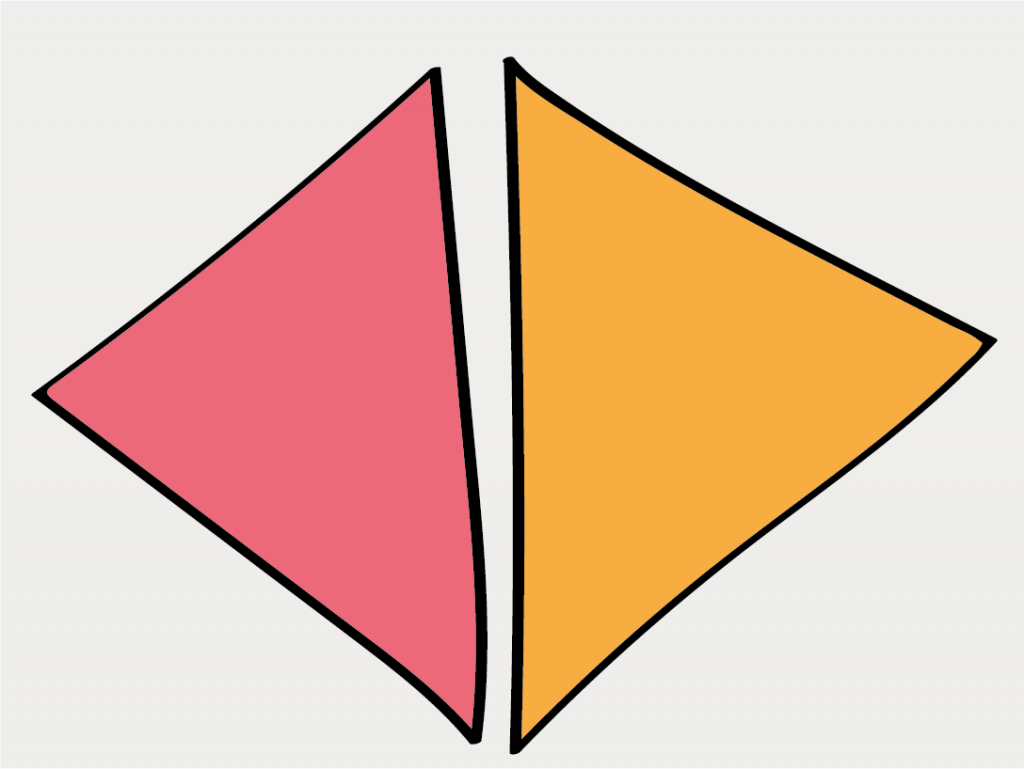

The diamond of Creativity

We know the diverging-converging stages as the ‘diamond of creativity’, because of the picture we draw with it, see figure 1.

Figure 1: The diamond of creativity: diverging-converging or diverging-evaluation if we follow Guilford (1968)

Who was the first to draw this picture? Honestly, I don’t know. I have some great sources to rely on but nobody knows for sure.

My best guess is that Osborn’s partner in crime, Sidney Parnes (I’ll get to him shortly) came with diverging-converging: the diamond of creativity. But I miss the source in which he would have mentioned that. Thus, at this moment, it remains an educated guess.

Before I go on to the first model of CPS I need to make one final remark. It is about the difference in idea generation phase and the diverging stage. That turns out to be a confusing difference.

Difference between idea generation phase and diverging stage

The idea generation phase comes after the problem definition phase. It is the first phase that focused on the solution. Generally, this phase takes place early in the CPS-process (Sawyer, 2012).

Like any other phase, the idea generation phase exists out of a diverging and a converging step. Thus, the idea generation phase is not the same as the diverging stage.

In the diverging stage of the idea generation phase, the focus is on finding ideas for a potential solution to the problem. And, for example, in the problem finding phase, the focus of the diverging step is on finding the right ways to formulate and clarify the problem.

Professionals who are new with brainstorming and creativity in workshops often believe that diverging equals idea generation. Because of that, they think diverging is always linked to finding a solution. But you can also diverge to find new problems or new information to define a problem.

See the difference? I hope so.

Now, let’s have a closer look at these 7, 5, 6, and 4 phase models.

Osborn’s first version of CPS

In Applied Imagination (1953), Osborn describes a creative process in seven steps. Puccio and Cabra (2009) refer to this model as ‘The Original Model’. Puccio and Cabra (2009) also mention that the first non-linear CPS-model comes from Isaksen, Dorval, and Treffinger (1994), the Components Model.

When we have read Osborn (1953) we find that it is more nuanced than Puccio and Cabra (2009) made us think it is.

Osborn’s seven steps of a creative process

The eleventh chapter of Applied Imagination is called ‘The processes of ideation vary widely’. In this chapter Osborn refers to these seven steps as ‘steps in a creative process’ (124). The steps are (Osborn, 1953: p. 125):

- ‘Orientation: Pointing up the problem.

- Preparation: Gathering pertinent data.

- Analysis: Breaking down the relevant material.

- Hypothesis: Pining up alternatives by way of ideas.

- Incubation: Letting up, to invite illumination.

- Synthesis: Putting the pieces together.

- Verification: Judging the resultant ideas.’

Osborn does not refer to these steps as steps in Creative Problem Solving but steps in a creative process, not the creative process.

I agree with Puccio and Cabra (2009) that we can view these steps as the first CPS-method. By the way, do you recognize Wallas’ four stages of control (CQ18) in these steps?! We could also say that Wallas created The Original Model of CPS.

Non-linearity

Osborn also mentions that creative processes do not have to include all of these steps:

[…]those who have studied and practiced creativity realize that its process is necessarily a stop-and-go, catch-as-catch-can operation – one which can never be exact enough to rate as scientific. The most that can honestly be said is that it usually includes some or all of these phases:’ (Osborn, 1953: p.125)

The next paragraph is also worth quoting.

‘In actual practice, we can follow no such one-tw0-three sequence. We may start our guessing even while preparing. Our analyses may lead us straight to the solution. After incubation, we may again go digging for facts which, at the start, we did not know we needed. And, of course, we might bring verification to bear on our hypotheses, thus co cull our “wild stab” and proceed with only the likeliest.’ (Osborn, 1953: p.125).

Thus, Osborn (1953) already mentioned the non-linearity of these process steps.

I also see some of Weisberg’s (2006) argumentation in this quote, that ‘our analyses may lead us straight to a solution’. We could interpret this as a reference to using top-down methods to solve a problem (CQ21).

Before I move on to the next ‘model’ of CPS, I have to explain some of the histories of CPS. I think it is important for understanding what comes next.

The Short History of CPS

To give context to the method, I will stay in the period when Coca Cola was advertised as a healthy drink for toddlers (I’m not joking, they really did this).

1953 – 1955

Alex Osborn

Alex Osborn stands at the cradle of CPS. Like I mentioned above, in 1953 Osborn’s bestselling book Applied Imagination was published.

I introduced Alex Osborn in CQ4 as a self-made businessman. He scraped himself through college, got fired at his first job, and became the director of an advertising company that employed over a thousand employees.

Osborn, like a true American, was eager to beat the Russian in the Cold War. He was on a mission to educate people in his brainstorm methods, with creativity the Americans would be able to outsmart the Russians. Read CQ4 for more on Osborn.

The Creative Education Foundation & CPSI

Osborn founded the Creative Education Foundation in his hometown Buffalo, at the University at Buffalo, New York in 1954. The goal of the CEF was to stimulate the education of creativity.

Then, in 1955 the CEF organized the first Creative Problem Solving Institute (CPSI). I think CPSI is a confusing name because it is not an institute as you would associate the word with. CPSI is the name of the conference.

Thus, the latest in 1955 the term Creative Problem Solving became a term. If it was Osborn that came with the name of this conference or someone at the CEF, I don’t know. I do know that Osborn moved from ‘creative thinking’ to ‘creative problem solving’ between 1953 and 1963. He showcases that in his revised version of Applied Imagination (1963):

I noticed that if you try to buy Applied Imagination on Amazon, you get a picture of the 3rd revised version from 1963 (the one Amabile used, see CQ19). Very subtle, Osborn changed the subtitle from ‘procedures and principles of creative thinking’ to ‘procedures and principles of creative problem solving’. Fun fact!

Sidney Parnes

If I understand it correctly, organizational psychologist Sidney Parnes was present at this first CPSI in 1955. Apparently, he loved it so much, he decided to team up with Osborn.

Sidney Parnes was a key person development and success of CPS. Parnes was able to ‘scientificy’ CPS. Although, according to my colleague he was not taken seriously by the psychologists at the Utah Conferences, that were held in that period by creativity psychologists (see CQ4), CPS managed to establish a great name among creativity practitioners.

1966 and 1967

Osborn dies in 1966. In that year Parnes publishes a book called ‘Instructors Manual for Institutes and Courses in Creative Problem-Solving’. A year later the book is published again, by the same publisher, under a different name: ‘Creative Behavior Guidebook’ (Parnes, 1977). Nice iteration. In this book Parnes explains the first ‘real model’ of CPS, the five-step model, see next paragraph.

According to Sawyer (2012), 1967 was also the year the CEF moved from University at Buffalo to SUNY Buffalo State College in 1967. Yes, you read it correctly, there are two State Universities of New York in Buffalo.

And according to the CEF (2015), 1967 was also the year they founded the Journal of Creative Behavior.

The rest of the history

When CEF relocated to SUNY, the academic unit of the CEF was renamed to ‘International Center for Studies in Creativity’ (ICSC). The CEF remained to exist as the publisher of the Journal of Creative Behavior and the organizer of CPSI.

ICSI is the only place in the world, as far as my knowledge goes, where you can obtain a Master’s degree in Creativity. That could explain some of its popularity.

In 2008 CEF relocated to Massachusetts (Sawyer, 2012), although Google maps also show CEF in Buffalo, maybe a dependence.

Read the History page of the CEF for a further detailed timeline of CPS.

Now I go on with the next model, the first real ‘model’ of CPS.

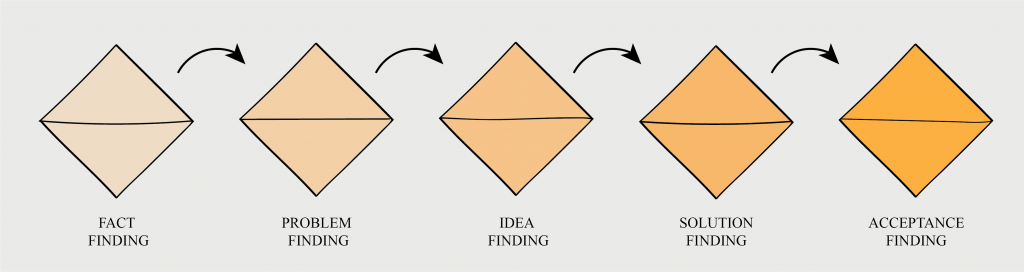

Osborn-Parnes 5 step model

Parnes (1967) describes a 5 step model of CPS. Unfortunately, I do not yet have access to Parnes (1967), the book is on its way. Thus, we follow Parnes (1977) and Puccio & Cabra (2009).

The Parnes-Osborn model, as Puccio & Cabra (2009) call it, had five steps. And I assume this is the first time we see a picture with the model. Something like the picture below, figure 2.

Figure 2: Osborn-Parnes CPS-model from 1967 (Puccio & Cabra, 2009)

I assume Parnes (1967) does describe this as a linear model. However, I cannot tell if he didn’t make similar remarks on non-linearity as Osborn did in explaining the steps of this model.

Evolution of CPS-models leading to the 6 steps model

After Parnes (1967) published this model on CPS, many iterations followed. For example, Parnes (1988) added ‘objective finding’ before ‘fact-finding’, and successors of Parnes, Isaksen, and Treffinger (1985) replaced ‘fact-finding’ with ‘mess-finding’ and ‘data-finding’ (Puccio & Cabra, 2009).

Like I mentioned above, Isaksen, Dovral, and Treffinger (1994) were the first to create a non-linear version of CPS (Puccio & Cabra, 2009).

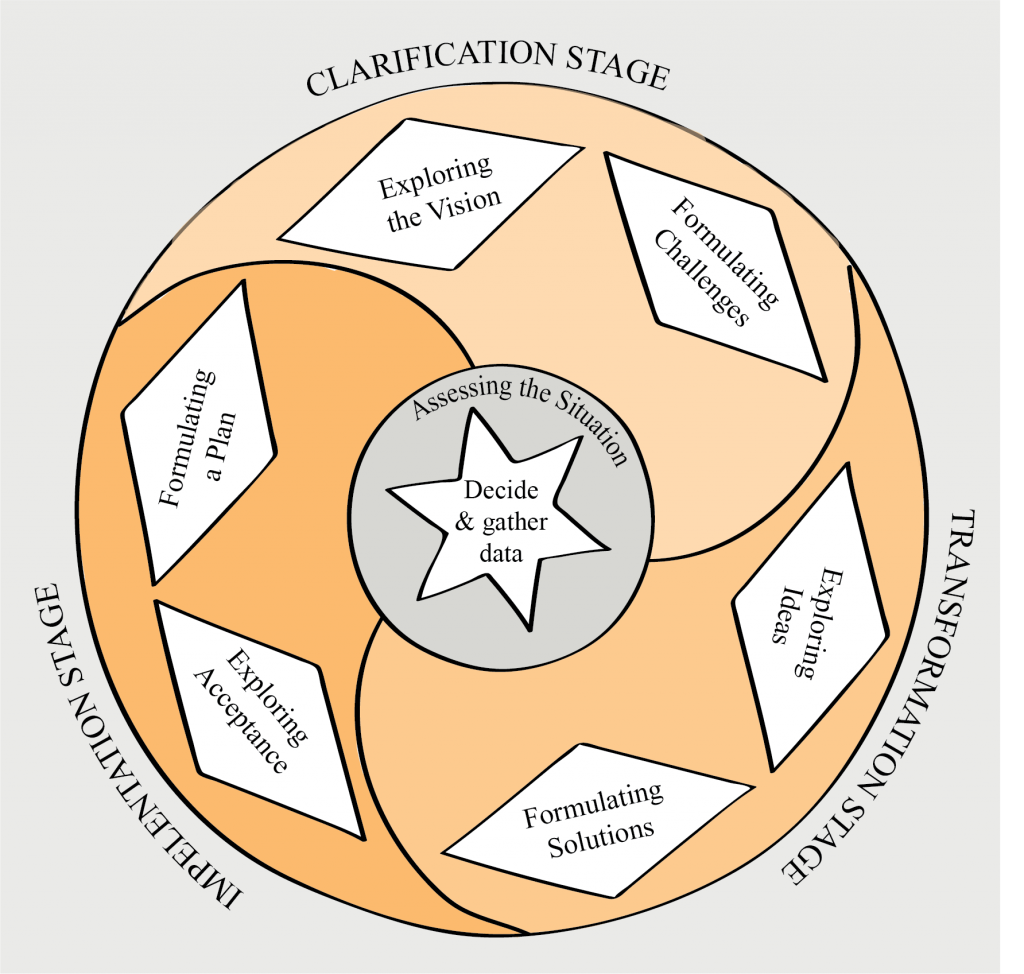

Puccio & Cabra (2009) mention a total of ten different CPS-models. They end with the six-step model called Thinking Skills Model by Puccio, Murdock, and Mance (2007). That model looks like this:

Figure 3: Thinking Skills CPS-model, based on Puccio, Murdock, and Mance (2017) (Puccio & Cabra, 2009)

This model uses three phases and within each phase, we see two sub-phases. Each sub-phase exists out of a diverging and converging stage. The model is circular but we ‘normally’ start at the top with ‘clarification’. In the middle of this model, we see a circle to represent ‘assessing the situation’. Assessing the situation is a continuous stream gathering information and making decisions.

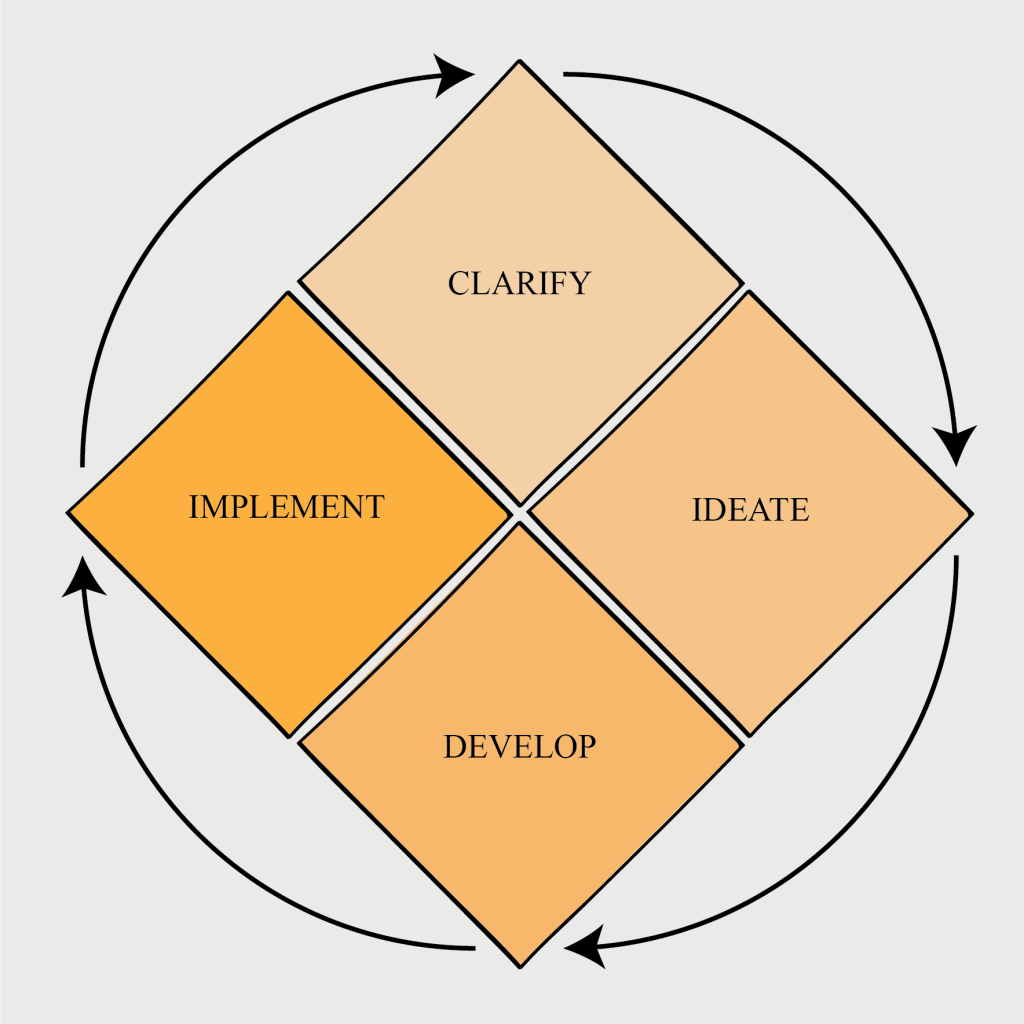

4 step model website CEF

The latest model I can find is on the website of CEF, which they published in 2015. That model exists out of four steps, Clarify, Ideate, Develop, Implement, see figure 4. The biggest difference of this model between this 4-step model and the 6-step model by Puccio, Murdock, and Mance (2007), is the separation of the transformation phase into two phases: ideate and develop. Bear in mind that the CEF represents the more practical side of CPS and that the ICSC the more applied-theoretical side of CPS.

Figure 4: CPS-model, based on the CPS-model shown on the website of the Creative Education Foundation.

4 points for consideration

Finally, I have four points of consideration for creativity trainers and facilitators. I know I promised also to elaborate on the similarities and differences between problem-solving and creativity. And the difference between problem-solving and creative problem-solving. I will not keep that promise. I will take it with me for next week’s article on the relation between Design Thinking and creativity. Problem-solving might play a central part.

On implementation and acceptance finding

In Puccio, Murdoch, and Mance’s (2007) model of CPS, acceptance finding is part of the implementation, and implicitly mentions as the third stage. That is something I strongly disagree with.

Firstly, if you decide to put ‘acceptance finding’ on the same level as ‘idea exploration’ or ‘formulating solutions’, it should be at the beginning. If you want others to like your solution you need to involve people from the beginning, basic organizational psychology.

It would be better if you place acceptance finding as a ring outside the model, like Buijs & Van der Meer (2013) did in their Dutch version of CPS, called Integrated Creative Problem Solving.

Secondly, we should ditch implementation in general. Implementation implies that you top-down force a solution upon employees. I have seen and heard of many ‘creative sessions’ that were used to fake influence by employees on the solution. That’s a shame. I know top-down organizational structures are still popular, also in American literature. But we will find in chapter 10 that innovation and creativity need different types of organization. Implementation is a term that is part of old-school thinking, in which people are a Human Resource instead of a Human Being.

A term like ‘stakeholder involvement’ could be another dimension to the model to replace implementation and acceptance finding. What’s in a word…

What type of method is CPS?

Yes, what type of method is CPS? This is a question I find difficult to answer. I give you three options.

- Is CPS a method to come from a problem to an executed solution? Thus a method to reach innovation.

- Is CPS a method to come from a problem to a solution in a workshop? Thus a way to structure a creative session.

- Is CPS a method to train people in creative thinking? Or even more confusing, is CPS a method to train people in CPS

CPS as an innovation method

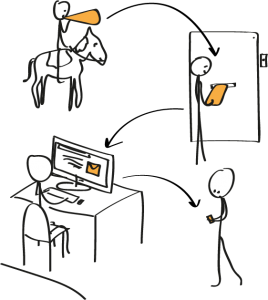

I see a lot of comparison in the 4 step CPS-method by CEF, and the picture I drew on the process of creating creative output in innovation in CQ15. See figure 5 below.

Figure 5: The difference between creativity and innovation (see CQ15)

I missed the clarification phase in this picture, but all the other phases are present. Ideation (that idea), Development, and Implementation (Introduction and Use). The phase or stages might be similar, the difference lies in the activities that happen in these stages.

Where in CPS all phases exist out of diverging-converging, in the development of a real product we also have producing and testing of a product. What we sometimes forget is that in producing and testing, we also encounter problems to solve. For example, figuring out how to produce or test an idea to get wanted answers.

The question is, do we always have to use diverging-converging for those problems? What about the differences between task-problems and people-problems that we encounter in a real innovation process (see CQ22)? Think about it.

Structure of a creative session or training method?

I see CPS used in training on ‘creative thinking’, but also in sessions in which people are asked by the facilitator to ‘think creatively’ about the problem they want to solve in that session. Thus, CPS is used as a training method as well as a facilitation method.

The question we have to ask ourselves is: should CPS be applied differently in a training setting and a facilitating setting? And if so, how different.

Learning by doing

We can also go for a ‘learning-by-doing’ training. Thus we use CPS as a method to solve a problem and by doing so, the participants get trained in the method. We also see this the other way around. In training on CPS, the participants use real problems as cases to use in the training.

Of course, when you are learning a new method through a real-life problem you care about, you could have a conflict of interest as a participant. You rather solve the problem than learn a new method. This is a point of attention for the facilitator or trainer.

The Holy Diamond of Creativity

At the beginning of this article, I mentioned that some facilitators talk about CPS when they talk about ‘the creative process’. Especially the division between creating options and choosing options, the ‘diamond of creativity’, seems like a holy process. A process we cannot question. Which is why I think we should question it.

I have showcased other ideas on creative processes in the previous chapters (CQ20, CQ21). We don’t always have to use the diamond of creativity. What about using judgment when creating options, but with keeping an open mindset?

From experience, I can tell that practicing in the division between creating options and choosing options helps in training yourself in openmindedness. That doesn’t mean that in every problem that I solve I first deliberately create options and then choose them. How often do you use this diamond of creativity to solve your own problems? Think about it.

What’s next

Next week I hope to figure out the relation between problem-solving, creativity, and design thinking. If I manage to do that, I will have a glass of champagne!

Below you find the cards for next weeks.

Willemijn

References

- Buijs, J. Van der Meer, H. (2013). Integrated Creative Problem Solving. The Netherlands, Nijmegen: Eleven International Publishing.

- Creative Education Foundation, www.creativeeducationfoundation.org, retrieved June 2020.

- Guilford (1968). Creativity, intelligence, and their educational implications. San Diego, CA: EDITS/Knapp.

- Osborn, A. F. (1948). Your Creative Power. New York: Scribner Press. 6th print.

Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking. New York: Scribner Press. 9th print. - Parnes, S. J., Noller, R. B., and Biond, A. M. (1977). Guide to creative action. New York: Scribner’s Sons.

- Puccio, G. J., and Cabra, J. (2009). Creative Problem Solving: past, present and future. In Rickards, T., and Runco, M. A. (Eds.). The Routledge Companion to Creativity. New York: Routledge.

- Sawyer, R. K. (2012). Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Wallas, G. (1926/2014). Art of Thought. Kent: Solis press.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. Hoboken: NJ: Wiley.

References used by Puccio and Cabra (2009) that I mentioned in this article

- Isaksen, S. G., and Treffinger, D. J. (1985). The basic course. New York: Bearly Ltd.

- Isaksen, S. G., Dorval, K. B., and Treffinger, D. J. (1994). Creative approaches to problem solving. Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

- Parnes, S. J. (1967). Creative behavior workbook. New York: Scribner’s Sons.

- Puccio, G. J., Murdock, M. C., and Mance, M. (2007). Creative Leadership: Skills that drive change. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ15: What is the difference between creativity and innovation?

I recently became the new President of the European Association of Creativity & Innovation (EACI)*. From that perspective, it would be nice to cla

CQ9: Are we all geniuses?

We all believe that Mozart, Einstein, Picasso Da Vinci and so on were geniuses and very creative. Why is that? And why don’t we believe we geniuses ou

CQ13: Could Einstein paint like Picasso?

Could Einstein paint like Picasso? No. And Picasso was no brainiac like Einstein was. We give both men credit for their great creative contributions,

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.