CQ16: There is no such thing as Creative Thinking

I finished Robert Weisberg’s 600+ page book on creativity in 2016. Weisberg (2006) concludes that creative thinking doesn’t exist. He makes a strong case for this claim. You can imagine my feeling of disillusion.

I finished Robert Weisberg’s 600+ page book on creativity in 2016. Weisberg (2006) concludes that creative thinking doesn’t exist. He makes a strong case for this claim. You can imagine my feeling of disillusion.

Weisberg’s argument starts with the weird use of the adjective ‘creative’.

The meaning of ‘creative’

To quote Weisberg: ‘When one says of someone that he or she is “thinking creatively,” one is commenting on the outcome of the process, not on the process itself.’ (Weisberg, 2006: p104).

I have questioned this weird use of an adjective myself more often. In the term ‘creative thinking’, ‘creative’ is an adjective that is applied to ‘thinking’. So by saying creative thinking, you are saying that the thinking itself is creative. Thus, you say that the thinking itself is original and meaningful (or any other words you want to use).

We do this with creative thinking and also with the creative process, which we should call the creativity process. At the Delft University of Technology, we have an amazing course in which we teach students how to facilitate creativity. The name of the course is Creative Facilitation. Same mistake.

I think you get the point. There is a consequence though.

If you refer to the thinking or process in itself being creative, that doesn’t mean that the result has to be creative. You can have a non-creative result from super original and meaningful thinking. And I guess we want to say the exact opposite.

By the way, there seems to be less confusion for the word ‘innovation’. When we are referring to processes that lead to innovation we call these processes ‘innovation processes’. But when we are referring to a process that is innovative in itself we say ‘innovative process’.

Weisberg’s argument

Weisberg (2006) argues that it is ordinary thinking that may lead to creative results. Ordinary thinking exists out of the following activities: remembering, imagining, planning anticipating, judging, deciding, determining, perceiving, comprehending, recognizing, interpreting (Weisberg, 2006, p.106). He uses two examples, the Guernica by Picasso and the discovery of the Double Helix DNA by Watson and Crick, to give the body to his argument. Picasso’s Guernica is a painting about war. He made a zillion drawing and paintings before he started his masterpiece, he was constantly imagining, planning, anticipating, judging and deciding what to do. The same goes for the discovery of the Double Helix. It was not a discovery falling out of the sky. There was a lot of all the thinking activities involved that led the two researchers to this creative result. Thus, in both cases, ordinary thinking led to a creative result. (Weisberg, 2006).

If we follow Weisberg’s (2006) argument, we can conclude that creative thinking is a combination of all kinds of thinking activities, not to be framed as a specific type of thinking.

Thinking activities and creative thinking

Let’s assume Weisberg (2006) is wrong and there is such a thing as creative thinking. I mean not in the wrong use of an adjective way, but truly as a combination of certain thinking activities. Let’s see if we can find definitions and explanations on creative thinking that could enlighten us.

Here’s what I’ll do. I’ll discuss the ideas from the folks that have written on creative thinking. I chose the ones of which I know that have been influential in theory and/or in practice. Bear in mind that this list is incomplete.

With that, I will start a table with five columns in which I will summarize the ideas from the people I’ll discuss. See table 1 below, I filled out Weisberg already. I will leave columns open when I have no substantial answer or when I simply don’t know.

|

Who |

Thinking |

Thinking activities |

Creative thinking |

Non-creative thinking |

|

Weisberg (2006) |

Ordinary thinking |

|

X |

X |

I’ll start with Aristotle.

Aristotle

Remember Aristotle from CQ8, to think is to associate ideas (Dacey, 2011). That’s a nice and ‘simple’ definition to start with.

This idea about thinking has survived through time, but it changed from thinking into creative thinking:

‘Creative thinking has been defined in associative terms, with the prediction that individuals tend to generate problem solutions in concatenated chains of associations’ (Runco & Cyirdag, 2011: p.485).

I’m adding Aristotle and Runco & Cyirdag (2011) to the table.

|

Who |

Thinking |

Thinking activities |

Creative thinking |

Non-creative thinking |

|

Weisberg (2006) |

Ordinary thinking |

|

X |

X |

|

Aristotle (Dacey, 2011) |

Association of ideas |

Associating |

|

|

|

Runco & Cyirdag (2011) |

|

Associating |

Generation of problem solutions is concatenated chains of associations |

|

When we speak of creative thinking I feel we should discuss with Guilford. It was after all part of his life work to try to measure human intellect, thinking. And creative thinking holds a special place in that his theory.

Guilford

I made a mistake

Before we start I have to admit I made a mistake. Oh no, wait, this was a learning moment?. I found out while I was reading Guilford (1968) for this article. I’ve been stating (CQ4) that Guilford defines creativity as a combination of divergent and convergent thinking based on Guilford (195). But that was untrue. I will create CQ4a as an addition to CQ4 to put things right. I will do that in May, and it is interesting stuff, something extra to look forward to.

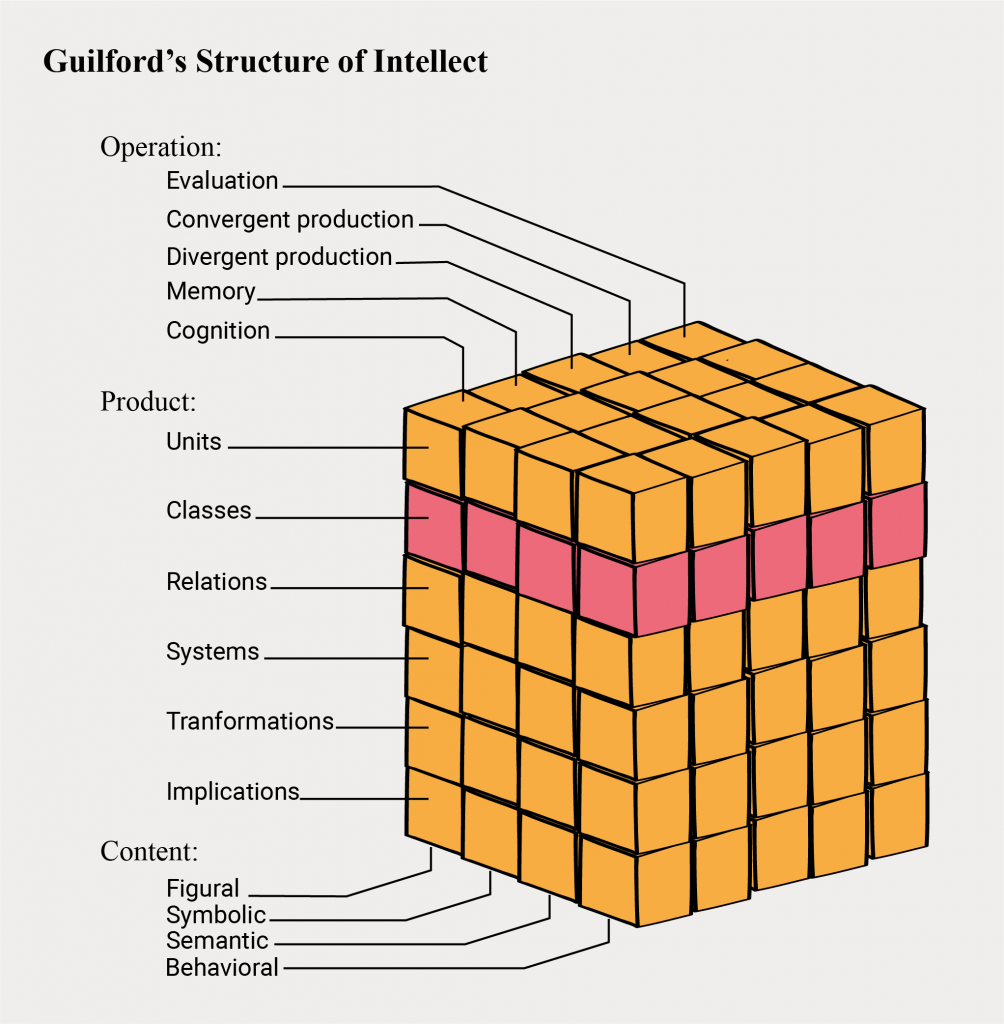

Now, we can start with Guilford’s definition of creative thinking. And to do that I have to explain his grand theory on the ‘structure of intellect’.

Structure of intellect

Guilford’s theory is based upon what he calls the structure of intellect (Guilford, 1968: pp. 14-22). In this theory, human intelligence has ‘three faces’ (p14): content, product, and operation.

In the context of this article, the operation face is most interesting. I’ll quote Guilford (1968) as much as possible, to the extent that I feel it is still appropriate. We start with the five classes in operation of the structure of intellect (Guilford, 1968: p16), see figure 1 below.

- ‘Cognition means discovery or rediscovery or recognition.

- Memory means retention of what is cognized.

- Two kinds of product-thinking operations generate new information from know information and remember information.

- In divergent-thinking operations we think in different directions, something searching, sometimes seeking variety.

- In convergent thinking, the information leads to one right answer or to a recognized best or conventional answer.

- In evaluation we reach decisions as to goodness, correctness, suitability, or adequacy of what we know, what we remember and what we produce in productive thinking.’

Figure 1: based on: ‘The structure-of-intellect model, representing the intellectual abilities classified in three intersecting ways’ (Guilford, 1968: p.10).

You might see how Guilford follows Wertheimer’s theory (CQ11)? If not, let me just say that Wertheimer’s book is called ‘Productive Thinking’.

Now we have these five classes of operations. The questions are which classes form creative thinking? And then how?

Classes involved in creative thinking

I think it is pretty obvious that divergent-production takes part in creative thinking according to Guilford. He says the following at the beginning of this book:

It is in the divergent thinking category that we find the abilities that are most significant in creative thinking and invention (Guilford, 1968: p.8).

Guilford also discusses the role of the other classes in creative performance. But not specific in creative thinking, which is sort of confusing. He says:

‘There are other abilities outside the divergent-production category that make some contribution to creative performances in their own ways. We have seen that one of the cognition abilities – sensitivity to problems- has a function in getting the creative thinker started. Evaluative abilities should have their uses, whether judgment is postponed or not, in determining whether the products of thinking are good, useful, suitable, adequate, or desirable. If the creator is to finish his job, he will eventually appraise his product, and he will revise it if he feels that revision is called for.’ (Guilford, 1968: p.108).

My question would be, are any of these abilities also contributing to creative thinking? Or is contributing to creative performance the same as contributing to creative thinking? I think Guilford implicitly assumed the latter. In that sense, Guilford is also falling into the trap of making the wrong use of an adjective.

Truth is, I cannot find a definition of creative thinking in Guilford (1968). Guilford’s structure of intellect exists out of 120 factors. In creative performance, and thus creative thinking (like stated above, I think this is how he meant it), is a combination of components:

‘It is my view that the creative disposition is made up of many components and that its composition depends upon where you find it. Practically all investigators recognize that there are many potentially contributing conditions.’ (Guilford, 1968: p.99).

Weisberg vs. Guilford

If you read the quote above, you might see how that matches Weisberg’s argument. It is in many types of ‘normal’ thinking that combined leads to creative performance, depending on the situation.

Where Weisberg goes for a cognitive approach with 11 factors or types of thinking. Guilford goes for a more complex approach with 120 factors. But the conclusion is the same: there are is no specific combination of these factors that define creative thinking in itself.

Thus, we fill out the structure of intellect in our table of thinking.

|

Who |

Thinking |

Thinking activities |

Creative thinking |

Non-creative thinking |

|

Weisberg (2006) |

Ordinary thinking |

|

X |

X |

|

Aristotle (Dacey, 2011) |

Association of ideas |

Associating |

|

|

|

Runco & Cyirdag (2011) |

|

Associating |

Generation of problem solutions is concatenated chains of associations |

|

|

Guilford (1968) |

Structure of Intellect |

Operations in classes of this structure of Intellect:

|

A combination of 120 factors, depends on the situation.

|

|

Newell, Simon, and Shaw

Like Weisberg (2006), Newell et al. (1958) take the problem-solving approach towards creative thinking and assume that: ‘creative thinking is simply a special kind of problem-solving behavior’ (p.4). Cool, it’s simple. I thought it was difficult but it is hopeful that they think it is simple…

Here is what makes problem-solving creative and thus defines creative thinking in their view (Newell et al., 1958: p.4):

‘Problem-solving is called creative to the extent that one or more of the following conditions are satisfied:

- The product of the thinking has novelty and value (either for the thinker or for his culture).

- The tinking is unconventional, in the sense that it requires modification or rejection fo previously-accepted ideas.

- The thinking requires high motivation and persistence: either taking place over a considerable span of time (continuously or intermittently), or occurring at high intensity.

- The problem as initially posed was vague and ill-defined, so that part of the task was to formulate the problem itself.’

Condition one, two and four say nothing about the thinking itself, it is about the outcome. Only condition two refers to a type of thinking, namely unconventional. In this context, my question is: how does unconventional thinking work? Moreover, I disagree with condition four, I think that also well-defined problems could ask for creativity, or in their words: problem-solving. But that is of minor importance in this context.

I chose to mention this view because Newell & Simon (I don’t know about Shaw) are known in creativity research but maybe not so known with practitioners. Keep them in mind. Their theory on human problem solving is relevant in today’s view on problem-solving, creativity and design. I’ll get to that in the chapter on design thinking.

Below you find Newell et al. (1958) in our table of creative thinking.

|

Who |

Thinking |

Thinking activities |

Creative thinking |

Non-creative thinking |

|

Weisberg (2006) |

Ordinary thinking |

|

X |

X |

|

Aristotle (Dacey, 2011) |

Association of ideas |

Associating |

|

|

|

Runco & Cyirdag (2011) |

|

Associating |

Generation of problem solutions is concatenated chains of associations |

|

|

Guilford (1968) |

Structure of Intellect |

Operations in classes of this structure of Intellect:

|

A combination of 120 factors, depends on the situation.

|

|

|

Newell, Simon, and Shaw (1958) |

Problem-solving |

|

Simply a special kind of problem-solving behavior through unconventional thinking |

|

Moving on with the Madonna of Creativity Research: Teresa Amabile. (I keep writing Amability, which sort of sound like an ability to be nice, haha).

Amabile

Amabile (1998) writes the following: “creative thinking […] refers to how people approach problems and solutions – their capacity to put existing ideas together in new combinations. The skill itself depends quite a bit on personality as well as on how a person thinks and works.”(Amabile, 1998: p3).

This quote doesn’t give us a lot, creative thinking refers to how people approach problems. I want to know what that ‘how’ is. But Amabile takes the performance view on creative thinking.

‘Because of complexities in observation and assessment, it is quite difficult to rely on either person or process measures in identifying creativity. Product measures are considerably more straightforwards […]. If we take individual ideas or products that can reliably be identified as creative by experts, then we can look at the person qualities, the environmental factors, and perhaps even the thought processes corresponding to the production of those ideas and products.’ (Amabile, 1988: p.126)

And yet, in this article (Amabile, 1988), she uses ‘creative thinking’ eleven times. In those cases, she is doing what most are doing, using an adjective in the wrong way. What I find most intriguing is that she does refer to creative thinking skills and methods of creative thinking (Amabile, 1988). But I can’t seem to find anywhere what those skills and methods are. Maybe I’ll found out three weeks from now when I will dive into her model on creativity (CQ19).

Finally, I would like to discuss a creativity professional probably know: Alex Osborn.

Osborn

Alex Osborn (more on Osborn in CQ4), who we all know as founding father of brainstorming (and co-creation though is not credited for that), wrote a bestseller in 1953. This book is called Applied Imagination: ‘methods procedures and techniques towards creative thinking’.

There must be something in the book on creative thinking, you’d think! According to the index pages: 220-226 are about ‘creative thinking’. (I came to page 138 reading this book, I know, I should finish it…). Let’s what we find on page 220 to 226.

‘If we set aside a definite period for creative thinking, we can best lure the muse. […] “We should take time out for thinking up ideas-nothing else,” said Don Sampson. […] Sampson rightly recommends mornings for thinking, afternoons for routine.’ (Osborn, 1953: p.220).

Then follow another, at least ten examples, of when you would have the most chances of getting a creative thought. The examples are about incubation or doing a low cognitive task, like shaving. It is all about having the best idea in the shower (see CQ10). In this part of his book, Osborn is also referring to creative thinking as a way of thinking to get creative thoughts. It is not about the thinking itself. He is also making the famous mistake.

Creative and non-creative imagining

However, check the title of the book again: Applied Imagination. We could say that Osborn defined creative thinking as applied imagination. The longer I think about the more I see the brilliance in the title. What does Osborn say about Imagination?

In chapter 10 of Applied Imagination, Osborn described Creative and non-creative forms of imagination. OK, maybe we are talking about Applied Creative Imagination? Of course, I’m dying to find out what the difference between creative and non-creative imagination is.

To start of the chapter, Osborn uses mental capacities from college presidents Donald Cowling and Carter Davidson (Osborn, 1953: p.108):

- ‘Ability to concentrate

- Accuracy in observation

- Retentiveness of memory

- Logical reasoning

- Judgment

- Sensitivity of association

- Creative imagination’

I don’t know Cowling and Davidson, and Osborn leaves no reference…

Then Osborn groups these seven mental capacities into four mental powers (because capacities and powers are different things?). He does admit that this classification is not a scientific one and only to help us understand creative thinking better. Here they are (Osborn, 1953: pp.108-109):

- ‘Absorptive power: the ability to observe, and to apply attention.

- Retentive power: the ability to memorize and recall.

- Reasoning power: the ability to analyze and to judge.

- Creative power: the ability to visualize, to foresee, and to generate ideas.’

And he adds:

‘In absorbing and retaining, we make our mind serve as a sponge. In logical reasoning and in creative imagining, we make our minds think.’ (Osborn, 1953: p. 109)

That is something we can use for our table!

Osborn separates creative imagination from non-creative imagination. Non-creative imagination involves worry and troubled thinking, creative imagination has a positive connotation to it (Osborn, 1953: pp. 109-115).

Osborn’s ideas on creative thinking and creative imagining remind me of ‘thinking fast and slow’ (Kahneman, 2011) and of ‘deep thinking’ (Kasparov, 2017). Where Weisberg (2006), Amabile (1988, 1998), Guilford (1968), Newell et al. (1958) take a more deliberate or conscious approach, Osborn is going for the spontaneous creativity (see CQ10).

We can add Osborn to our table.

|

Who |

Thinking |

Thinking activities |

Creative thinking |

Non-creative thinking |

|

Weisberg (2006) |

Ordinary thinking |

|

X |

X |

|

Aristotle (Dacey, 2011) |

Association of ideas |

Associating |

|

|

|

Runco & Cyirdag (2011) |

|

Associating |

Generation of problem solutions is concatenated chains of associations |

|

|

Guilford (1968) |

Structure of Intellect |

Operations in classes of this structure of Intellect:

|

A combination of 120 factors, depends on the situation.

|

|

|

Newell, Simon, Shaw (1958) |

Problem-solving |

|

Simply a special kind of problem-solving behavior through unconventional thinking |

|

|

Osborn (1953) |

Logic reasoning & creative imagining |

The mental capacities:

|

Creative imagining |

Logic reasoning & non-creative imagining |

Conclusions so far

There is no such thing as creative thinking. At least not in as a special type of thinking. What would be truly interesting is to see how these different types of thinking activities from all these authors mentioned above relate to each other. I think if we want to be a comprehensive body of knowledge on creativity, starting with how we think might be a good start.

What/who’s missing in this article

Though I will wrap up this article I feel I’ve left out too much. You probably miss Edward De Bono with his ‘lateral thinking’. And if we discuss ‘thinking’ shouldn’t we look into philosophy and in neuroscience? You are right! In this article, besides De Bono, I miss John Dewey and Henri Bergson.

And I started with neuroscience in CQ10 with Dietrich (2004) and Carson (2010). Dietrich defines creative thinking as cognitive flexibility. That also sounds interesting. I hope I’ll be able to introduce this neuroscience when we are discussing creativity mindsets. But I’m not sure yet if De Bono, Bergson, and Dewey will return in this quartet.

TFCO

That having said I still think we should reconsider the use of ‘creative thinking’. If only to avoid miscommunication. How about ‘thinking for creative output’ (TFCO)? That seems more accurate to me.

When we try to stimulate TFCO in workshops, we could take different thinking activities in mind. In Weisberg language: Is the technique that is all about remembering, or imagining, or perceiving, etc.? Or in Guilford language is the technique all about divergent production or evaluation. The latter must sound comforting.

That is wrap for chapter three!!! A though one. Difficult topics and no time due to Corona. I’m scraping by and we keep on going! Next week I’ll introduce probably another difficult chapter on creativity theories. And trust me, there are a lot of them. You will find all the cards from this chapter below.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organizations. Research in Organizational Behavior (10), pp. 123-167.

- Amabile, T. M. (1998). How to kill creativity. Harvard Business Review, sept-oct.

- Carson, S. (2010). Your Creative Brain: Seven Steps to Maximize Imagination, Productivity, and

Innovation in Your Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. - Dacey, J. (2011). “Historical Conceptions of Creativity”, in Encyclopedia of Creativity: Second Edition, eds. Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R., London, UK: Academic Press, 2011, Vol 1. pp. 608-616.

- Dietrich (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 11(6), pp. 1101-1026.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), pp. 444-454.

- Guilford (1968). Creativity, intelligence, and their educational implications. San Diego, CA: EDITS/Knapp.

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking fast and slow. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Kasparov, G. (2017). Deep Thinking: Where Machine Intelligence Ends and Human Creativity Begins. London, UK: John Murray (publishers)

- Newell, A., Shaw, H. A., Simond H. (1958, May). The process of creative thinking. Paper presented before symposium at the University of Colorado.

- Runco, M. A. & Cyirdag, N. (2011). “Time”. Encyclopedia of Creativity: Second Edition, eds. Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R., London, UK: Academic Press, 2011, Vol 2. pp. 485–488.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ9: Are we all geniuses?

We all believe that Mozart, Einstein, Picasso Da Vinci and so on were geniuses and very creative. Why is that? And why don’t we believe we geniuses ou

CQ1: ‘Creativity is a lazy word’

Firstly, I wish you a happy, healthy and a h…[fill out your own h-word] 2020! Secondly, starting today I will post an article on creativity on my we

CQ13: Could Einstein paint like Picasso?

Could Einstein paint like Picasso? No. And Picasso was no brainiac like Einstein was. We give both men credit for their great creative contributions,

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.