CQ21: How do people solve problems?

The Cognitive Analytical Model (CAM) is described by Robert W. Weisberg in his 2006 book: Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention and the Arts. CAM is, as the name of the model gives away, an analytical approach towards creativity.

I referred to Weisberg (2006) many times before in this Creativity Quartet 2020. It was the first psychological book on Creativity I bought and studied, it took me two years. I made notes per page and I made a summary of my notes. In my summary, I tried to work as visually as I could. Thus, I can say, unlike in the previous two articles, I know this book.

Creativity is an ordinary process with an exceptional result

Weisberg (2006) argues that the cognitive processes that lead to a creative solution to a problem, are the same cognitive processes that lead to a non-creative solution to a problem. Weisberg (2006) therefore concludes there is no such thing as creative thinking (also see CQ16). To achieve a creative result we need to work hard and build expertise.

Building on Newell, Simon, and Shaw

Weisberg (2006) is building his theory on the ideas from Newell et al. (1962). We have heard those names before (CQ16 and CQ19)! Weisberg (2006) states that these men were leading the cognitive revolution in psychology, in the 1950s. In the cognitive view of creativity, it is normal processes that lead to creative outcomes. Newell et al. (1958) took this standpoint and argued that creativity is the same as problem-solving.

Weisberg (2006) follows Newell et al. (1958) in the way that he also believes that ordinary mental processes lead to creative output. However, Weisberg (2006) assumes that creative output is not only the result from problem-solving activities One can also come to a creative outcome when s/he is not trying to solve a problem:

‘There may be times when we think creativity without specifically solving a problem, but we may still do so using ordinary thought processes’ (Weisberg, 2006: p.102).

Herewith, Weisberg (2006) states that creativity may ‘bubble up’ while not solving a specific problem, although much of his argumentation involves problem-solving. I think that the underlying question that Weisberg tries to answer in his book is: ‘How do people solve problems?’

Focus on ill-defined problems

In this article, I will explain how Weisberg thinks people solve ill-defined* problems. Theory on problem-solving or problem finding forms the backbone of his theory on creativity. The difference between problem solving and creativity I will elaborate on in the next chapter. The first step is to describe a problem.

*In well-defined problems all components of the problem are defined, except the one variable that leads to the solution. In ill-defined problems, there are at least two unknown variables. Keep in mind that much research is done with well-defined problems but we can ask ourselves if the conclusions from well-defined problems can be extrapolated to ill-defined problems. I will get back to this point later in this article.

What is a problem?

States, moves, and spaces

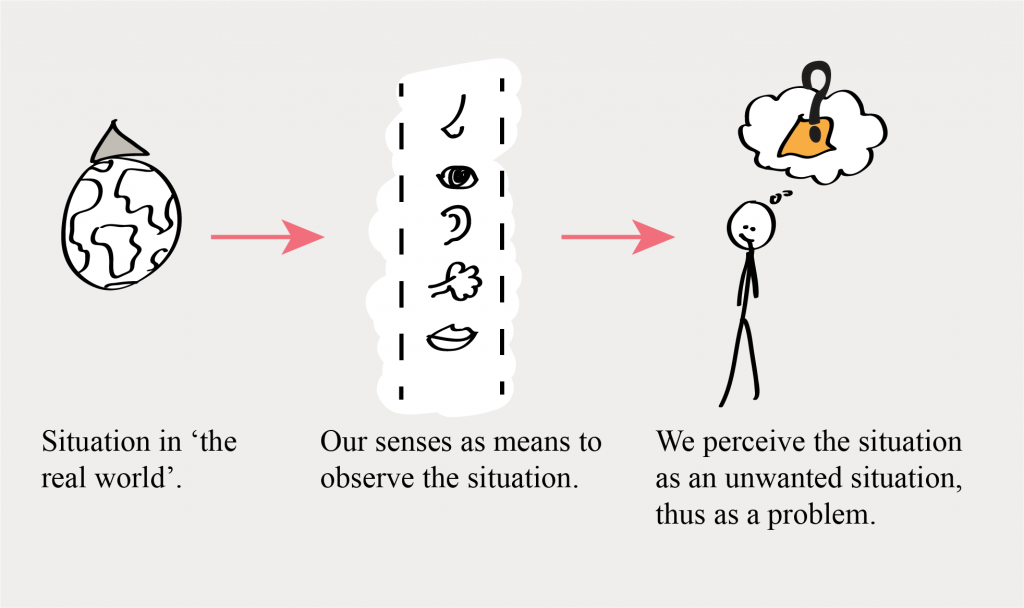

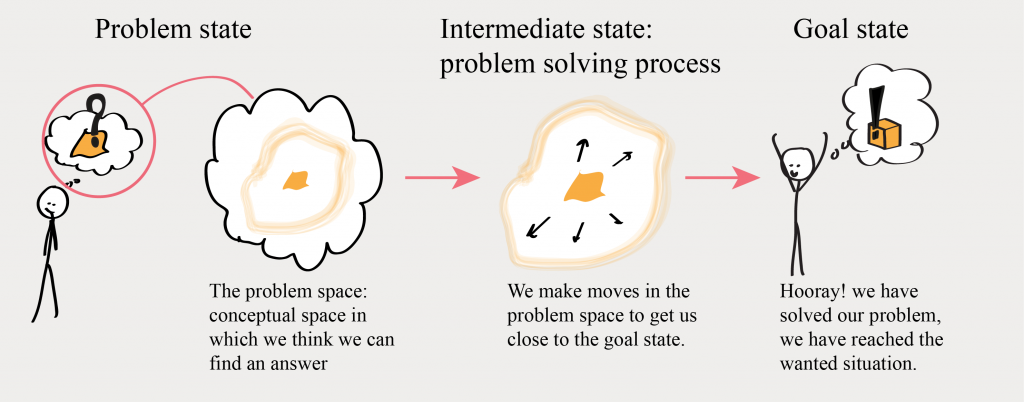

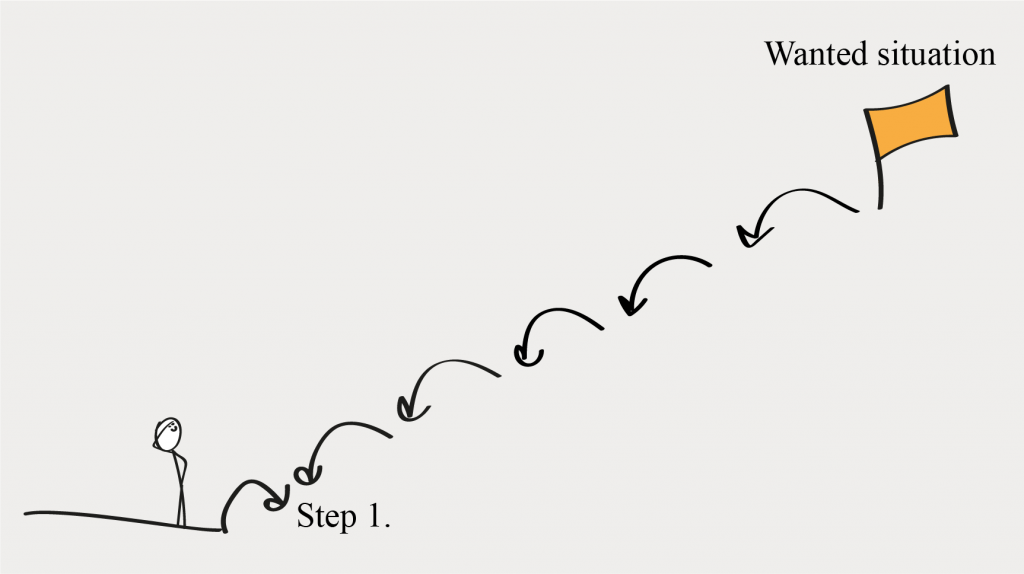

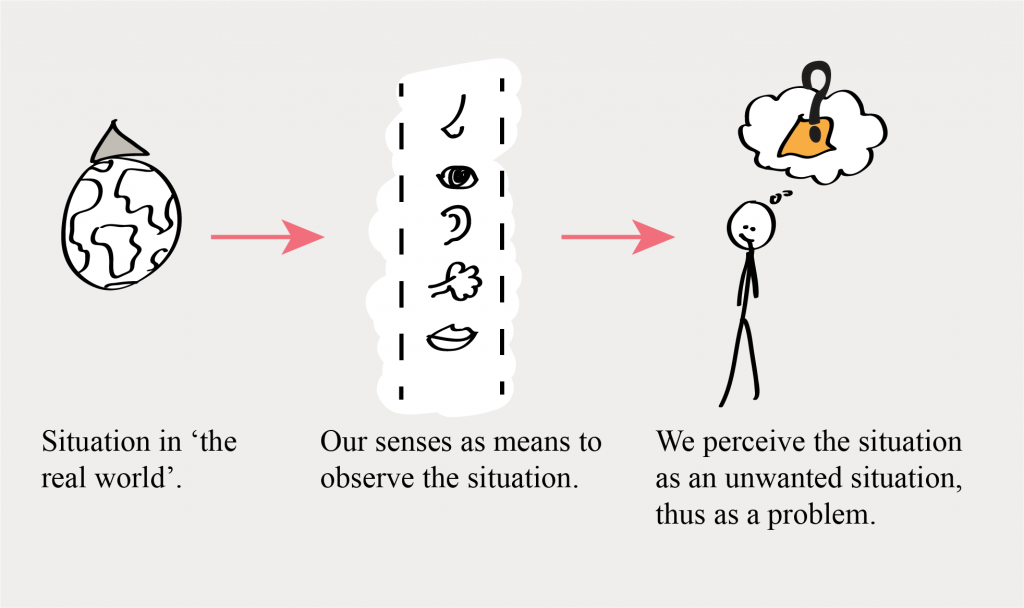

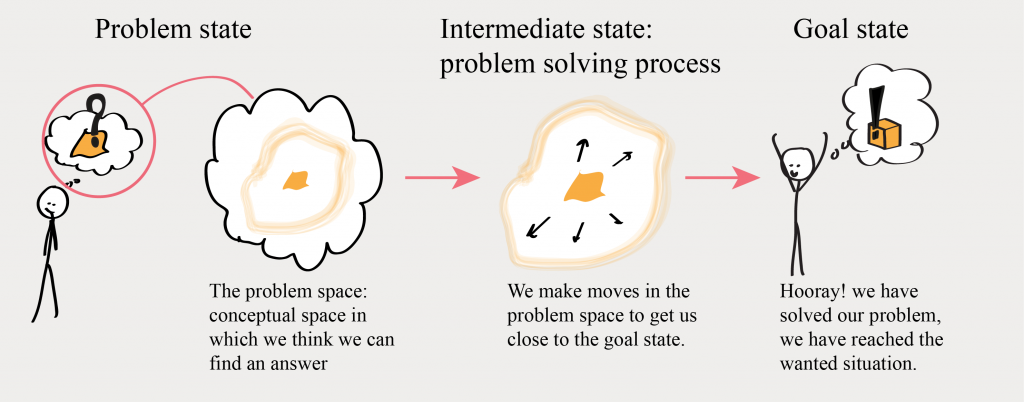

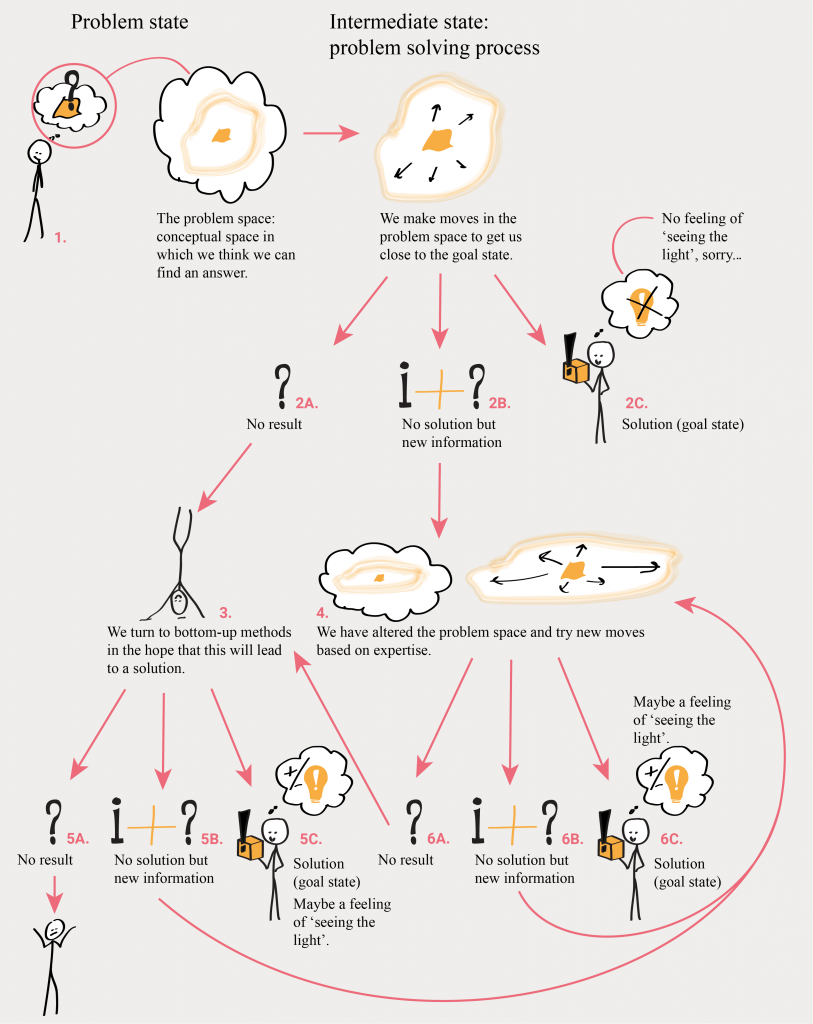

A situation becomes a problem when we experience the situation as a problem (see figure 1). A problem is an unwanted situation. This is what Weisberg (2006) refers to as the ‘problem state’. When we found a solution to our problem we have reached the ‘goal state’ and everything in between is called ‘the intermediate state’ (Weisberg, 2006) (see figure 2, below).

Figure 1: from situation to problem. In the metaphor of the picture: when a grey triangle becomes an orange shape that is not the desired shape…

When we find ourselves in a problem state, we consider the ‘conceptual space’ in which we think we can find a solution to the problem. This is called the problem space (Weisberg, 2006). You might want to call this The Box, from the phrase outside-the-box thinking (CQ5). Or: ‘This is my interpretation of the problem and this is more or less the direction I think the solution will lie’. As you can imagine, changing the problem space will have great consequences for the solution you will find.

In this problem space, we make ‘moves’ to get us closer to a wanted situation, to the goal state.

Intermediate state as problem-solving process

We can see this intermediate state as the problem-solving process. If the solution meets the requirements for creative output, we can define this problem-solving process is a creativity process, in hindsight. Weisberg’s requirements of creative output are ‘new for the thinker or culture’ and ‘unconventional’, in the way that it needs modification from previous ideas. More definitions of creative output you can find in CQ14 and CQ15.

Figure 2: from problem state to goal state

Top-down and bottom-up methods

According to Weisberg (2006), we make our moves through the problem space using two types of methods: top-down (also called ‘strong’) methods and bottom-up (also called ‘weak’) methods. For strong methods, we need expertise on the problem, where for weak methods we do not need expertise on the problem. Bottom-up methods are general methods we can always use, they do not require specific expertise.

Weisberg (2006) gives us examples and uses of these methods. Figure 3, gives an overview of these methods that can be used to solve ill-defined problems.

Figure 3: An overview of top-down and bottom-up methods, described in Weisberg (2006)

Bottom-up heuristic models

Heuristics were also part of Amabile’s (1996) componential model (see CQ19). Heuristics is a general method to solve problems based on what you know. Weisberg (2006) describes four types of heuristic models: hill-climbing, means-to-end analysis, working backward, and planning. I will focus on hill climbing and working backward. Means-to-end analysis and planning are methods that only make sense to use in solving well-defined problems, and that is not the focus of this article.

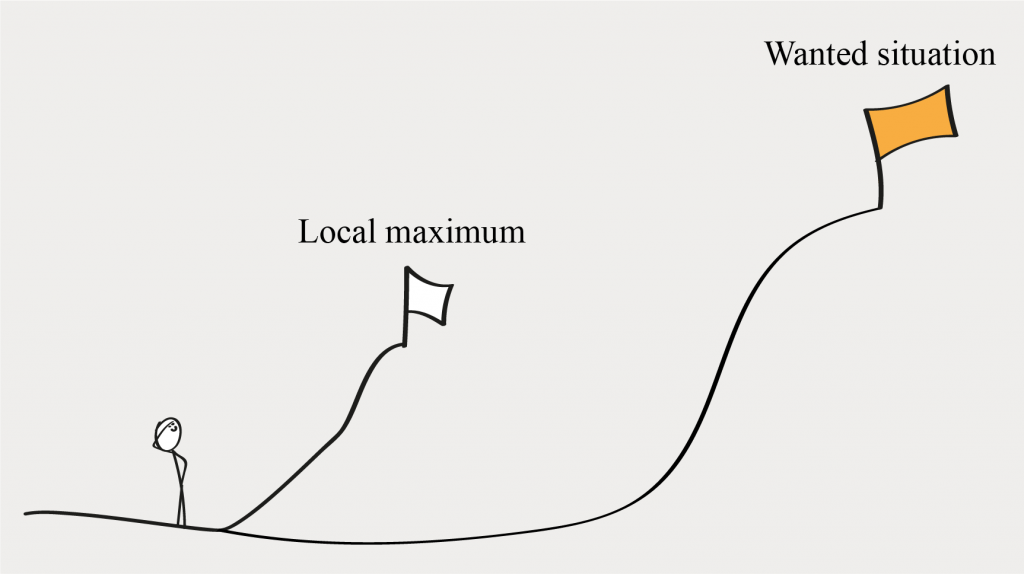

Hill climbing

Hill climbing is a method in which you take steps to make the next ‘intermediate state’ more the same as your goal state. Hill climbing works to a certain extent, but by taking these steps you might reach a ‘local maximum’ instead of finding the real solution you were aiming for. See figure 4.

Figure 4: Bottom-up method Hill Climbing, in its metaphor

I think Hill climbing is a popular method in the world of startups and design. Because we do not know how to reach the wanted situation, since we have no experience with the problem, we go by trial-and-error, which is basically what hill climbing is. You simply hope you picked the right route. And if you’re smart you pivot your way up the hill. Some take the wrong turn and will keep muddling in the pool, they only reach a local maximum, or the start-up will fail. That is a great chance to start again.

Working backward

You think about what you need for the desired goal and then consider what the criteria are for that desired goal. Then you consider the criteria as the end goal, etc., until you have reached your current situation and know the first step to take. See figure 5.

Figure 5: Bottom-up method Working backward

In design we call working backward backcasting. The method is used in many business strategy models: what is your mission? Then you make a roadmap towards that mission. And you know your first step.

Please, see this roadmap as a pencil draft, not as a marked predefined map. After ‘step 1 comes the next step 1’*. Because we are finding ourselves on untouched grounds, we can only assume. And we work with a ‘temporarily agreed reality’*.

If you don’t know these phrases, you should search online for improvisation techniques for professionals or search for the Rhineland organization ‘model’ (it is not truly a model). Or simply ask me.

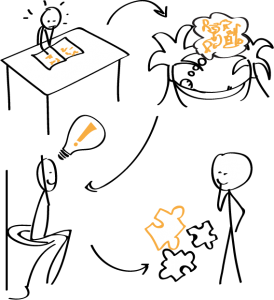

Gestalt view on problem-solving

Gestalt psychology is all about how we perceive what we observe. ‘Looking differently at the same thing’ is a phrase that comes from the Gestalt theory. Important in this theory is that creative insight happens in a flash, a sudden moment of illumination. That is why they call it ‘seeing the light’ (Wertheimer, 1945; CQ11).

Gestalt theory supports the idea that we need to break with the past, instead of building on the past to come to insight. That means that Gestalt psychologists argue that expertise negatively influences problem-solving. And thus, using the Gestalt methods to come to insight are not top-down methods that require expertise, but bottom-up methods that reject the use of expertise (Weisberg, 2006). See CQ11 for an elaborate story on Gestalt psychology.

Neo-Gestalt view on problem-solving

Gestalt theory lost popularity after WOII because the founders died young and they didn’t manage to train successors and because they weren’t able to prove their theory (Wagemans, 2015; CQ11). However, breaking patterns, breaking with the past, finding the ‘off-roads’, and changing perceptions are popular notions in business literature and blogs on creativity.

In the early nineties Kaplan & Simon (1990), and Ohlsson (1992) revived the Gestalt theory. Instead of the restructuring of a problem through a change in perception, the Neo-Gestalt theorist introduced heuristic methods to restructure the problem (Weisberg, 2006).

According to Ohlsson (1992), there are three types of these heuristic methods to help us to break an impasse and come to insight: elaboration, re-encoding, and constraint relaxation.

Elaboration

We can elaborate upon the problem space by studying the information from the problem space or by trying to recall information from long-term memory.

‘A representation can be changed by being extended or enriched. […]. A more productive representation can be obtained by adding the missing information, without revising or deleting existing information.’ (Ohlsson, 1992: p.13).

In workshops we use elaboration when we do a ‘purge’ on the problem as given (Heijne, 2019). In this step we tell the participants to write down (or draw) their thoughts on the problem. One of the goals is creating a complete understanding of the problem, we try to complete our information.

Re-encoding

Re-encoding is refers to the ‘looking differently at the same thing’-phrase and is about checking if the interpretations you make of the problem are correct. Like we say in the world of start-ups: ‘assumption is the mother of all f*ck-ups’. In Ohlsson’s words:

‘In many insights problems, the initial representation is fundamentally mistaken, rather than merely incomplete. In such a case, the thinker must abandon or reject some component of his/her current representation.’ (Ohlsson, 1992: p.13).

Constraint relaxation

Constraint relaxation is about our interpretation of the goal: ‘Unlike elaboration and re-encoding, constraint relaxation changes the mental representation of goal rather than of the given situation’ (Ohlsson, 1992: p.14)

For example, in the Nine-dot puzzle (see figure 6, and CQ5 for the answer) we think the solution should fit within the imaginary square of the nine-dots. Once we let go of that goal constraints, we have an opportunity to solve the problem.

Figure 6: The Nine dot puzzle. Try to connect all nine dots, with four straight lines, without removing your pen from the paper.

Difference between real and imaginary constraints

Ohlsson uses the example of the Nine-dot puzzle to explain this method. However, there is a difference between relaxing imaginary goal constraints and relaxing real goal constraints. Let’s take a closer look at the goal constraints for the Nine-dot puzzle:

- You have to touch all nine dots

- You have to connect all dots with 4 straight lines

- You are not allowed to remove your pen from the paper while doing this

Nowhere in this list of constraints is something that says ‘you have to keep your lines in the matrix of the nine-dots. Thus, we didn’t relax our goal constraints, we checked our assumptions.

In real life it can be difficult to separate imaginary goal constraints from real goal constraints. For example, you need to come up with a new type of power tool. One of the constraints is that the tool cannot weigh more than 5kg. Is this a real constraint or is it an imaginary constraint, and do you only think this is a constraint? If your boss tells you it should not weigh more then 5kg, you can take it as a real-life constraint. Or, and that way I would do, think for yourself if this 5kg constraint makes sense. Ask yourself, why 5 kg?

I’ve explained this issue in other words in CQ5. I think the differences between real constraints and assumed constraints for a basis for misunderstandings and it lowers energy. And like I said, what is a real constraint in the first place? Good stuff to think about on a Friday evening with a good glass of wine.

What about bottom-up methods with the use of expertise?

Gestalt theory is based on ‘insight problems’. Insight problems have one right answer. Insight problems are well-defined problems. And problems that do not need specific expertise. Therefore Weisberg (2006) refers to these methods as bottom-up methods.

However, I believe these bottom-up methods, together with expertise could be a great tactic to solve ill-defined problems (see CQ5). Like I have described in the three paragraphs above, these three types of restructuring I recognize as creativity workshop techniques. But I also recognize them as methods designers use to get from an abstract question to a concrete answer in the form of a product, service, process, or organization.

According to Weisberg (2006) we can use bottom-up methods in trying to solve any type of problem. We do not need specific expertise on the problem or the method to apply these methods. However, the chance that we solve the problem only by using bottom-up methods seems little.

Creativity research on heuristics uses problems that can be solved through bottom-up problems: ‘they are generally in their applicability, but precisely because of that generality they do not provide much specific information useful for solving any particular problem’ (Weisberg, 2006: p.147).

The problems we are trying to solve are ill-defined and often complex. If I look at these bottom-up problems I recognize them from my knowledge about creativity techniques and design methods.

If I understand it correctly, we use many bottom-up methods in workshops and in designing products and services. I have to agree with Weisberg (2006) that only by applying these methods we won’t get far. However, we bring our knowledge and expertise to the table. I always believed we also need expertise to solve ill-defined problems.

I wonder if it is possible to research problem-solving as a combination of bottom-up and top-down methods? Geneplore is at least an attempt to combine the two types of methods (see the next paragraph).

But most of all I wonder how a person like Weisberg views these creativity processes. Maybe we can guess his opinion after explaining his model. But first I need to explain Geneplore and the top-down model besides Weisberg’s (2006) own model.

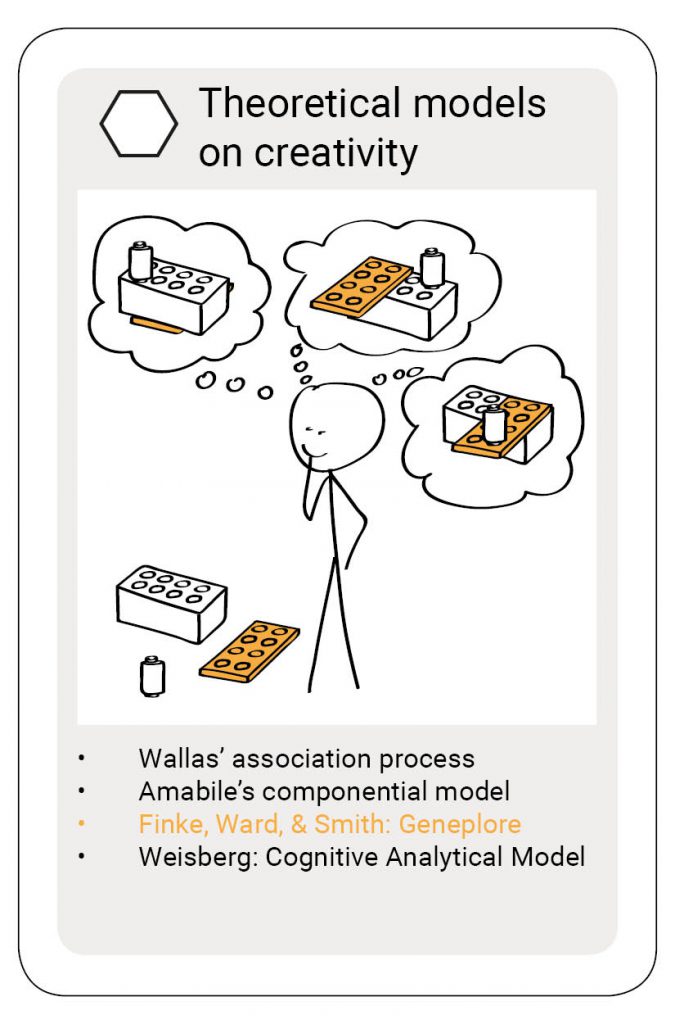

Creative Cognition Approach (Geneplore)

Not entirely accidentally Geneplore was the topic of the previous article (CQ20). Geneplore is a method that exists out of a generation phase and an exploration phase. In the first phase you ‘not-entirely-but-a-bit-randomly’ generate ‘preinventive structures’ (Finke et al., 1992) and in the second phase you use your expertise in a constructive and explorative way. It’s a pretty cool and hands-on approach. Read CQ20 to find out the more on Geneplore.

Geneplore is bottom-up and top-down

Geneplore is a combined bottom-up and top-down method. Generating the preinventive structures is not a per se problem-related activity, and is something anyone can do for any problem: a bottom-up method. The exploration phase has a top-down approach. You need to use your expertise, constructively and exploratively, to interpret these preinventive structures from the first phase.

Weisberg (2006) agrees with Finke et al. (1992) in two ways. Firstly, they both argue that creativity processes exist out of ordinary cognitive processes. They do use different types of cognitive processes. Secondly, they both use top-down and bottom-up methods in their model. Finke et al (1992) do not use these terms in their model, but we can see the overlap as I explained above.

Weisberg disagrees with Finke et al. (1992) in the order in which we use these models. In Geneplore we first use bottom-up and then top-down methods. In Weisberg’s Cognitive Analytical Model, we first use top-down methods, and then we use bottom-up methods, as we shall see below. We are only ‘Analogy Transfer’ away from CAM and since I’ll probably devote an article to Analogy transfer in a later stage, I’ll be short on this method.

Top-down method: analogy transfer

In analogy transfer we use information or principles from one situation and transfer that to another situation. Weisberg (2006) refers to analogy transfer as a strong method because you cannot use the method without specific knowledge. The methods above we can use for any problem, this method we can only use if we have expertise.

We have three types of analogy transfer: local, regional, and remote.

A researcher uses local analogy transfer when he applies the method she used for experiment A in experiment B.

A researcher uses regional analogy transfer when she uses a method to study SARS in a method to study COVID-19.

A researcher is using remote analogy transfer when the researcher on COVID-19 finds a medicine for the disease because he transfers the complex system of hurricanes and weather to the virus.

Maybe the latter is a weird analogy. I’m trying to connect the article to the news, which is something that is apparently a wise thing to do, awesome advice… A more famous analogy transfer is the discovery of the Benzene circle came to his discovery when he saw the circles of a snake and translated those rings to his problem: voilá the Benzene circle was a fact.

We all know analogy transfer

In business, we use analogy transfer all the time: when we are on a business trip, when we go to a congress or when we take sneak peeks at what competition is doing (regional analogy).

The question is always: ‘What are the principles behind the things they are doing, and how can we use that?’ Or: ‘What information I get from the inspiration, can I use in my problem?’

I always tell participants in courses with key-note speakers to listen and think at the same time. Try to find the ideas behind the words and see how you can apply the story to your own situation. This is ‘analogy transfer’. More on this, by the end of the Summer.

As far as I can tell, Weisberg only mentions analogy transfer as other top-down method besides his method. So we finally go to Weisberg’s model. We needed all the above models because Weisberg uses them in his model. Maybe I should have told you that earlier in the article, I hope you’re still with me.

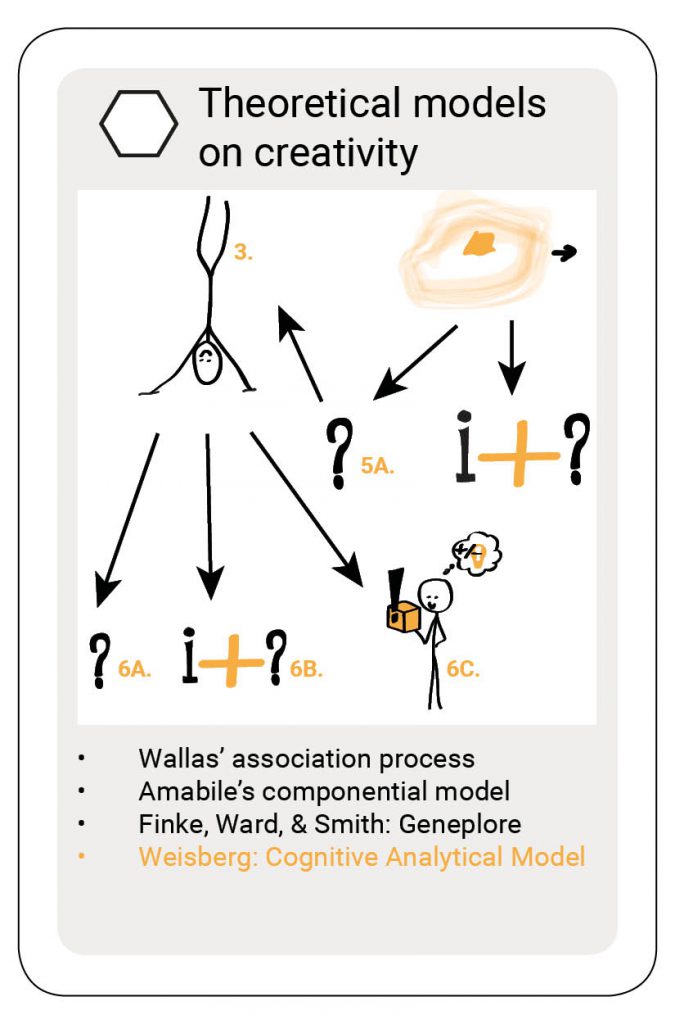

Cognitive Analytical Model (CAM) in six steps

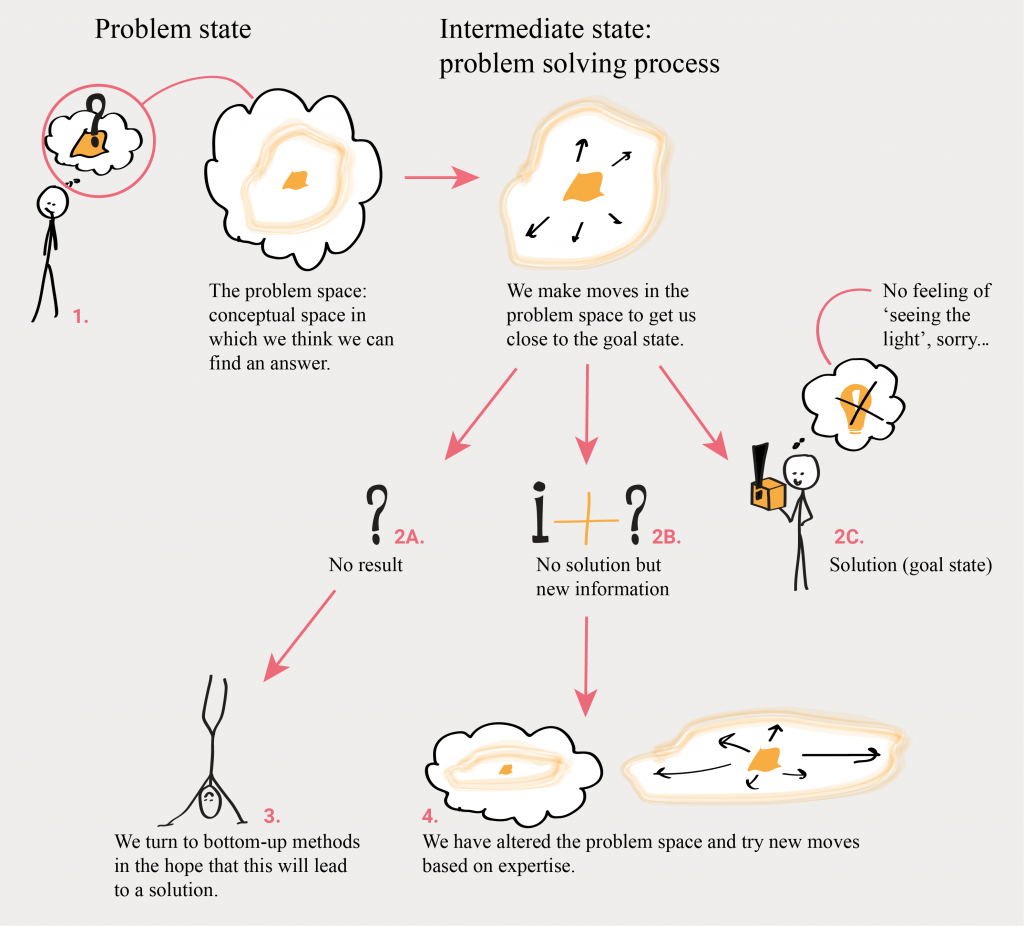

According to Weisberg (2006) problem solving a.k.a. creativity, happens in four steps. For an easier understanding I divided them into six steps, as you can read below.

Step 1: Interpreting, problem spaces, moves

Step one of Weisberg’s (2006) Cognitive Analytical Model is about the interpretation of the problem and finding a method that you think might help you in solving the problem. Remember the beginning of the article about situations, problem spaces, and moves? That is the first step of CAM. You can find figures 1 and 2 again below, to refresh your memory.

Once we have defined our problem spaces, and we can do this in a split second, we will scan our mind on ‘previous experiences from which we have learned and through which we have gained expertise’. We are trying to find expertise based methods we can use to solve the problem and we apply these methods to the problem (the moves).

*I’m writing this sentence in between quotation marks because there is research on the difference between the role of memory and experience and expertise in problem-solving. All terms differ from each other. If you’re interested, let me know, I have to look it up.

In figure 2 after we have made our moves we come to an answer and reach the goal state. That can be one of the results from our first attempt at solving the problem, as we shall see in the next step.

Step 2: the result of step 1

Step 2 is not really a step but a result. Once we have applied our own expert’s method to the problem, we get three possible results (see figure 7):

2A. No solution, no new information

The method didn’t bring you anything, you have no idea how to solve the problem. That means you have to find another way to solve the problem. Apparently our knowledge is not sufficient. If this is the case you go to step 3.

2B. No solution, but new information

You didn’t succeed to solve the problem with the method. But you did think of something. That something gives you knew information and with this new information you go to step 4.

2C: You have found the solution, hooray!

Actually, if you found the answer, you won’t feel the ‘hooray’. We are often creative (read: solving problems) without really noticing it. What am I cooking tonight? Road diversion, how will I drive to work? We are creating new solutions every day, nothing special. According to Weisberg (2006), we won’t have that feeling Eureka-feeling in these scenarios.

Figure 7: Weisberg’s Cognitive Analytical Model step 1 and step 2 (results)

Step 3. Use bottom-up approach

If we cannot solve the problem with the knowledge we have, our top-down approach failed. If our expertise does not help us enough to solve the problem. Then what? We then turn to a bottom-up approach. We can always try something and see if the result takes you closer to the desired situation (hill-climbing). We hope to make the problem space smaller by using heuristic methods. Or we try to use bottom-up methods from the Neo-Gestalt theory to change the problem spaces (restructuring the problem). See figure 8, below the next paragraph.

Step 4: You changed the problem space

In the first attempt to solve the problem, you didn’t get to a solution, but something in the strong methods that you used, did give you new information. With the coming of this new information your problem space has altered, in other words you have restructured the problem. See figure 8.

For example, if I don’t know what to cook tonight, my problem space will exist out of dishes and ingredients that I know. And even though there are flowers we can eat, flowers probably won’t be part of my problem space. But if I start to think about it, flowers can become part of my problem space, which will give me a whole new direction in which I can find a solution.

Figure 8: Weisberg’s Cognitive Analytical Model step 1 to 4

Step 5: results of step 3

The results from step three are similar, but slightly different, from the results I described in step 2 (see figure 9, below the next paragraph):

5A. No solution, no new information

If we have gained no new information and we have not found an answer, we reached a definite impasse, a stop. And there is no step after ‘stop’ in this model.

In reality there is! How about finding new information not within your cognition but in the outside world? Isn’t that what inspiration (see CQ8) is all about?

5B. No solution, but new information

We have altered the problem space, and we go to step 4. We stop using bottom-up methods and we return to using our expertise and top-down methods to continue our problem-solving process.

5c. You have found a solution, maybe hooray!

If we have used the neo-Gestalt, bottom-up methods, to solve the problem, there is a chance we get a feeling of Eureka. I don’t know how big of a chance.

Step 6: the results of step 4

The results from step 4 are also similar to the results I described in step two and step 5 (see figure 9).

6A. No solution, no new information

We turn to bottom-up methods and go to step 3.

6B. No solution, but new information

We take step 4 again.

6C. We have found a solution, maybe hooray!

The feeling of a moment of insight is possible because we have restructured the problem.

Figure 9: Weisberg’s Cognitive Analytical Model in six steps

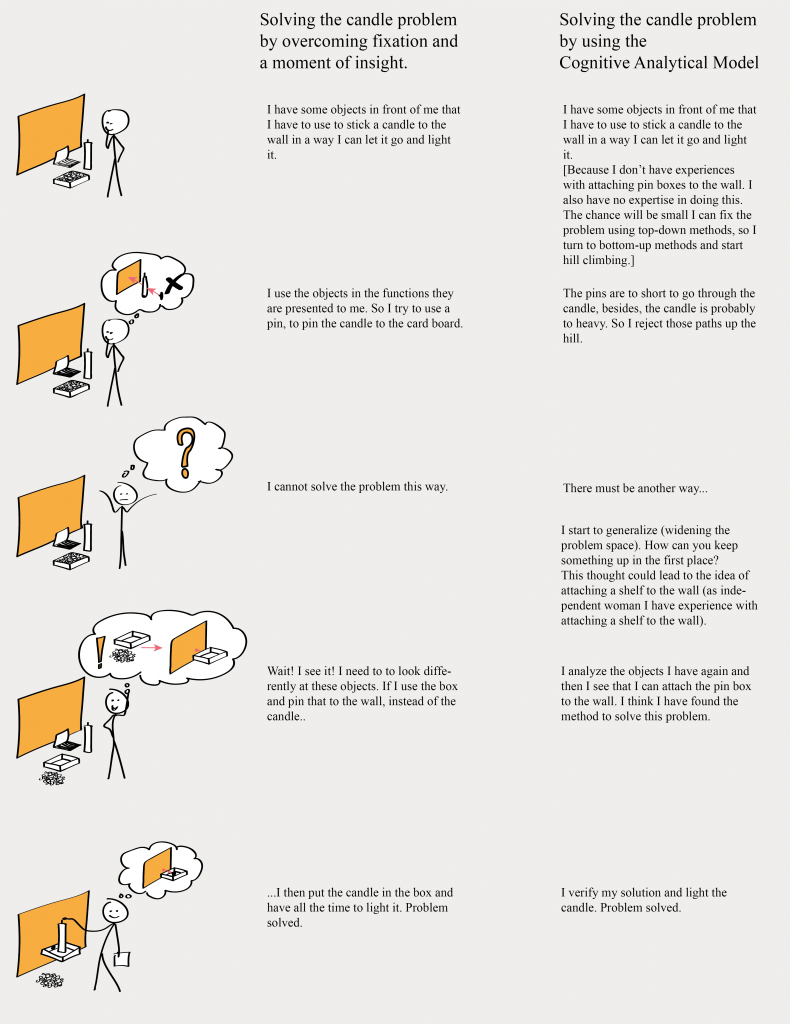

Before I go to the conclusions for this article and this chapter I will give an example of CAM vs. a Moment of Insight (CQ5). I will use the famous Candle Problem (see CQ11) as a case study.

Example of CAM vs Moment of Insight

Figure 10 explains how we can solve the candle problem in five steps. In the texts besides the pictures you will the words that fit the process of a Moment of Insight and overcoming fixation, and the words that fit the Cognitive Analytical Model.

Figure 10: Cognitive Analytical Model vs. a Moment of Insight

What can we learn from CAM?

I will share some first insights, there is of course much more we can learn from this model.

Top-down or bottom-up?

We can be more conscious about the use of bottom-up and top-down methods in our creativity workshops. Most techniques we use to stimulate creativity are either about restructuring information or are bottom-up techniques. There is no focus on the deliberate use of expertise, which is a missed opportunity in my opinion.

Brainstorming is a bottom-up technique

Brainstorming (CQ33) is a great example of a bottom-up technique: anyone can participate! There is a lot of critique on brainstorming for all the right but mostly wrong reasons (I will get to this in my article on brainstorming). If we see brainstorming as a bottom-up method, it can explain why and when brainstorming does and doesn’t work.

Ultimate restructuring with Post-its

Restructuring problems and alternating problem spaces is an important element from The Cognitive Analytical Model. The use of Post-it’s (not sticky notes, because post-its are the only type of sticky notes that work properly), helps us structuring and restructuring problems. We clarify the elements (the Post-it’s) and the relation between the elements of a problem (the position of the Post-it’s). In problem-solving, we can use visuals, wisely (not decoratively as some of the pictures I see on my Linked-in feed).

Overall I think we can learn a lot from this approach to the creative process, because it is so analytical. I did feel a bit deprived of my romantic idea about creativity. But I found it back in the act of being creative. Keep the energy going ladies and gentlemen!

Conclusion of this chapter

I have only described four theoretical models on creativity, and there are many more. It does help to describe four models because we see some interesting similarities and differences. Here is three final thought to overthink:

- Is the preparation stage from Wallas’ Art of Thought, the same as the top-down methods described by Weisberg?

- What comes before and after Geneplore?

- Are Amabile’s creativity relevant skills not also ordinary cognitive processes?

- Please add your own thoughts…

Next week, next chapter!

In the following weeks we will dive into the world of deliberate creativity methods. I will give the background of the most used creativity methods, as far as I can tell:

- Creative Problem Solving

- Design Thinking

- Synectics

- TRIZ

You will find the cards for this quartet below. Thanks for reading and I wish you a pleasant continuation of your day.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in Context. New York: Avalon publishing.

- Heijne, K. & Van der Meer, H. (2019). Road Map for Creative Problem Solving Techniques. Boom uitgevers Amsterdam, The Netherlands.

- Kaplan, C. A., and Simon, H. A. (1990). In search of insight. Cognitive Psychology, 22, 374-419.

- Newell, A., Shaw, H. A., Simond H. (1958, May). The process of creative thinking. Paper presented before symposium at the University of Colorado.

- Ohlsson, S. (1992). Information-processing explanations of insight and related phenomena. In Keane M. T. and Gilhooly K. J. (Eds). , Advances in the psychology of thinking (Vol. 1. pp. 1-44). New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Wagemans, J. (2015). Historical and conceptual background: Gestalt theory. In: Oxford Handbook of Perceptual Organization, Ed. Wagemans J. Oxford UK: Oxford University Press.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

- Wertheimer, M. (1982). Productive Thinking. Chicago: Univ of Chicago.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ15: What is the difference between creativity and innovation?

I recently became the new President of the European Association of Creativity & Innovation (EACI)*. From that perspective, it would be nice to cla

CQ18: Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, Verification

You know that feeling when you finish a book, close the cover, hold it in front of you, and you think: ‘WOW!’? I had that with the Art of Thought from

CQ14: What is Creativity?

Understanding how people create has been a serious topic for philosophy since the Renaissance (CQ9). But when Guilford acknowledges creativity to be a

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.