CQ22: Deliberate creativity methods

Can we be creative by choice? The word ‘deliberate’ implies we can. In this chapter I will describe four methods all based on the idea that we can be creative deliberately. In this article I will elaborate on the word ‘deliberate’ and I will shortly explain the methods that will be part of this chapter.

Can we be creative by choice? The word ‘deliberate’ implies we can. In this chapter I will describe four methods all based on the idea that we can be creative deliberately. In this article I will elaborate on the word ‘deliberate’ and I will shortly explain the methods that will be part of this chapter.

Deliberate as in intention to get a result

We use deliberate creativity methods to help us to get to creative output. We have the intention to create originality and meaningfulness (or novelty and usefulness, see CQ14 and CQ15). In business we always, yes always, use deliberate creativity methods to solve a problem. All deliberate creativity methods I describe in this article are problem-solving methods. Thus the intention is to solve the problem. We can also see deliberate creativity as a process. Let’s remind ourselves what neuroscientists say about deliberate creativity as a conscious process.

Deliberate as in a conscious process

In CQ10 I’ve written a paragraph about the difference between spontaneous creativity and deliberate creativity, from a neuroscientific perspective. According to Dietrich (2004), our brain uses different modes of processing information: deliberate and spontaneous processing modes.

Deliberate processing modes

When we gain insight (read a creative result) from deliberate processing modes, our insights were formed in the prefrontal cortex, in our conscious brain. Deliberate processing modes are structured and fit our internal belief systems (Dietrich, 2004).

According to Carson (2010), the advantage of deliberate processing modes is that we can control them, and we ‘understand’ because they are transparent to us. For example, if we get an insight this way, we can logically reason where this insight came from.

Spontaneous processing modes

In spontaneous processing modes our insights come from our unconscious, not from our prefrontal cortex. We do not actively look for information in our consciousness. Unconscious thoughts are ‘more random, unfiltered, and bizarre to be presented in working memory’ (Dietrich, 2004: p.1016) than conscious thoughts.

According to Carson (2010) the advantage of spontaneous processing is that the possibility of insight is higher than in deliberate processing modes:

‘When you think consciously and deliberately, your attention is focused and you can only process one thought at a time; however, spontaneous thoughts appear to originate below the level of conscious awareness where processing occurs in parallel, meaning that multiple ideas using a wider database can be processed at the same time’. (Carson, 2010: p.60).

Why would we then focus on deliberate creativity methods, if unconscious methods have a greater chance of leading us to creative output? Because solving a problem in the real world is more than coming up with a good idea.

Why focus on deliberate creativity methods?

What if I have a spontaneous idea for the solution of a problem I’ve been deliberate trying to solve for ages? Is that deliberate or spontaneous creativity?

According to Dietrich (2004) and Carson (2010) we should define this as spontaneous creativity. However, this ‘spontaneous idea creation’ only refers to the moment of insight. And we know from CQ5, CQ11, and, C21, that the moment of insight doesn’t exist or at least doesn’t tell the complete story.

Think about Wallas’ association process of Preparation, Incubation, Illumination, Verification (CQ18). We deliberately, consciously work on a problem (preparation) we then incubate and come to a spontaneous illumination. Dietrich (2004) is only considering the moment in which one gets the idea, not the entire process that leads up to that idea.

Dietrich (2004) and Carson (2010) do give an interesting neuroscientific explanation of why incubation positively contributes to creativity. And we can use incubation in deliberate creativity methods. For example, I can (deliberately) go for a walk to take my mind off things. Thus I can choose actions that might stimulate spontaneous idea creation.

I think that we use deliberate creativity methods to structure our creation process, to help us in our preparation, but also to give us the input to increase the chance of spontaneous creativity to occur. And besides that, we can also take the deliberate-spontaneous approach, as a conscious choice for a mindful course.

And so, in this fifth chapter of my Creativity Quartet 2020, we will focus on deliberate creativity methods. The question I need to answer is, which ones to choose?

Considerations in choosing deliberate creativity methods for this quartet

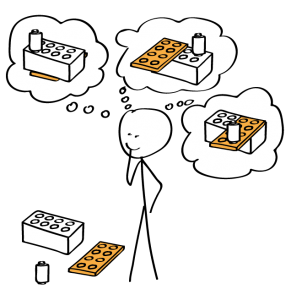

Firstly, I make a difference between a technique and a method. I don’t know if there is a scientific difference between method and technique, they feel like distinct issues to me. A technique can be part of a method.

The output of a creativity technique is hopefully new and meaningful elements, inspirations, subsolutions, that help solve the problem. The output of the creativity method is the problem solved.

For example, brainstorming is a technique that can be used in the method of Creative Problem Solving. Design Thinking is a method (that is not true by the way, I get to that in CQ24), Design Sprint is a technique. In the last case, the technique is a method squeezed in a short time frame, I wonder if that is such a good idea…

Secondly, due to the structure of this project, I have room for four methods. I chose the methods that are widely used and deserve some closer attention.

Here they come.

Creative Problem Solving

Of course I will start Creative Problem Solving (CPS). I think CPS is the most famous and used deliberate creativity method in the Western World. I’ll explain the method, go back to the foundations of the method, and give the underlying assumptions and principles of the method. And I will focus on the relationship between problem solving and creativity. I hope that works out…

Design Thinking

Defining the relation between creativity and design thinking has been on my list for at least a year. We are creating a Minor at Delft Universiteit of Technology, at the Faculty of Industrial Design Engineering. I am not satisfied with the relationship we have defined so far. Moreover, design thinking is ‘super hot’ at the moment. I sometimes get frustrated by the abuse of the term and the misunderstanding of design in the critique on design thinking. I will clear the air in this article.

Synectics

‘The word Synectics, from the Greek, means the joining together of different and apparently irrelevant elements.’ This is the first sentence from the book Synectics (Gordon, 1961). The method was developed by William Gordon and George Prince. Their method involves a ‘deep way’ of analogy transfer. Synectics is often simplified as analogy transfer, that does not tell the complete story. I intend to tell that story in CQ25.

TRIZ

TRIZ is a Russian acronym for Theory of Inventive Problem Solving. I think TRIZ is less known than CPS or Design Thinking. It is, as far as I know, the only non-Western method that stuck in the West. TRIZ was invented by a Russian, Genrich Altshuller. He worked at a patent office and studied over forty thousand patents to distillate 40 principles behind new inventions.

I’m not yet convinced if TRIZ is a method. It might be a technique. I take this chance to familiarize myself better with TRIZ. If it turns out to be a technique, so be it.

Interesting note: engineering methods

Three out of the four methods that I will write about in this article have been developed in an engineering background. At first I thought that must be because of my own bias because I was educated as an engineer.

In a chat with anthropologist and Professor Bregje van Eekelen, one of my co-developers of the Minor on Creativity, I came to realize that something else is going on.

Bregje mentioned that in engineering literature we see much interest in creativity. In Art or Architecture literature, creativity is less of a topic. Why is that?

Her first guess was that creativity is so evident in the Arts that people don’t see the urgency of researching it. And I think that has to do with the type of problems we are solving.

People problems and task methods?

As a painter the problem you have is transferring your emotions to a white canvas, using paint. The problem is internal, personal, and fluid.

An engineering problem is external, not personal, and often dealing with forces of nature: if a screw doesn’t fit a hole, it doesn’t fit.

Creativity seems more urgent to investigate in the latter case because we need to find a solution to how that screw can fit in that hole. This is a ‘hard criteria’.

In creating art, because the problem is fluid, there are no hard criteria for the solution. As long as the painter feels he is expressing his emotion on the canvas, he is solving his problem and he is creating creative output.

There is another variant

In the engineering problems I described as external problems, people are not directly part of the problem (in real life we always are). But in other types of business problems, f.e. sales problems or UX-problems, people are a bigger part of the problem (and the solution).

What happens if we use methods to solve a task problem, as methods to solve a people-problem?

For example, how many of us used brainstorming as a workshop technique in a workshop on team collaboration? I know I did. The results are always the same: we need to communicate better. That is a non-result.

In the following weeks we will find out how these deliberate creativity methods, which are developed in an engineering background, deal with non-engineering problems that involve people.

What’s next

Next week I will elaborate on CPS!

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References

- Carson, S. (2010). Your Creative Brain: Seven Steps to Maximize Imagination, Productivity, and

Innovation in Your Life. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. - Dietrich (2004). The cognitive neuroscience of creativity. Psychonomic Bulletin and Review, 11(6), pp. 1101-1026.

- Gordon (1961). Synectics: The development of creative capacity. New York, NY: Collier Books.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ2: Creativity in The West anno 2020

The West anno 2020: we all need to be creative. The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) research ‘The Future of Jobs’ (2016) stated that creativity would be

CQ20: Geneplore: theory ready for practical use

Geneplore is a merge of two words: generate & explore (Finke, et al., 1992). The Geneplore model is described in a book called Creative Cognition,

CQ3: ‘Creative industries’ should go

Last Summer I was at a creativity conference with the title: Dutch Creativity Festival, organized by the ‘ADCN: Club for Creativity’. I did not check

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.