CQ19: Three Components of Creative Performance by Amabile

Teresa Amabile (1950-going strong), distinguished and retired Harvard Professor, but as many retired professors, still working. Last Summer at the Creative Conference in Ashland Oregon, I called her the Madonna of Creativity Research, to her face.

Teresa Amabile (1950-going strong), distinguished and retired Harvard Professor, but as many retired professors, still working. Last Summer at the Creative Conference in Ashland Oregon, I called her the Madonna of Creativity Research, to her face.

Disclaimer

Amabile has been researching creativity for over forty years. The main source for this article is her book from 1996, Creativity in Context. I have not fully studied the book. I read bits and pieces to write this article. That means that this article will skim the surface of her rich work. Nonetheless, I believe that with this article I give an overview of the main elements of her model on creativity.

In this article, I will first explain why I chose Amabile’s model. Then I will elaborate on her model on creativity. I will end the same way I end all articles, with a sneak preview of next week.

Why Amabile?

Amabile has been influential in both theory and practice, for three reasons. One, she opened up a new research field. Two, she invented a new assessment technique. Three, she was at Harvard. I will elaborate on these reasons.

One, a small anecdote

Amabile was, together with Dean Keith Simonton (the first to create a comprehensive theory of the social psychology of creativity. Like Amabile, Simonton was also at the conference in Oregon. Both were keynote speakers, of course. Simonton received his Festschrift* at the conference as well, Amabile was part of it.

*A Festschrift is a book or presentation, in this case, to honor a respected person especially in the world of academics.

Amabile held an engaging story about her first encounter with Simonton. They came in contact with each other because they were both interested in the social psychology of creativity, which was a new approach to creativity research. She had a nerdy picture of him, based on their contact through phone and mail, Amabile pictured Simonton as a super nerd. Glasses, tiny guy, the whole nerd package. When she finally met him and she discovered he was looking like the popular guy from any chick-flick. She showed a photo of Simonton in his twenties during her speech, and indeed we see a handsome young man.

I don’t know, you had to be there. I thought it was pretty funny, and she told the story well.

Anyway, it was not only that she was leading the way into the field of social psychology. She also invented a method to assess creative performance. The Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT).

Two, the Consensual Assessment Technique

With the CAT, researchers use experts’ opinions on the level of creativity in the produced results from a task given to research subjects. For example, teachers or painters judge the paintings of children, who are instructed with a certain paint task. If the majority of the experts judge the performance as creative (so there is consensus, hence consensual assessment) then the product gets a creativity stamp.

The CAT is the first assessment technique that could measure real-life creativity. And although it is by no means perfect, the CAT is sometimes referred to as the “Golden Standard” of creativity assessment (Bear, 2010).

Indirectly, her pioneering work in the field of social psychology, and the CAT that made her popular in the professional/business world. The missing link is Harvard.

Three, Amabile @ Harvard

Amabile did groundbreaking (my words) work on the role of motivation in creativity. Her research earned her a spot at Harvard. In 1995 she became a professor of Business Administration at Harvard.

Her work primarily focussed on individual creativity. At Harvard, her research focus shifted towards leadership and organization and innovation. That seems like logical steps, being at Harvard and all. Find her Harvard profile here and her C.V. here.

Her reputation and the name of the university she works for increased her fame in the World of Business. Amabile advised large companies in the USA and international governments, on creativity, leadership and, innovation (at least according to her Wikipedia page).

Now, after this extensive introduction of Teresa Amabile, we are now ready to explore her model on creativity. I will first explain componential models in general, so we know what we are dealing with. Second, I will give Amabile’s definition of creativity and her basic assumptions. Thirdly, and finally, I will introduce her componential theory.

What is a componential model?

As the word implies, a componential model is a model that exists out of multiple components. Componential models are also called confluence models. Because these components are interrelated and the level of creative output is determined by a combination of these components. Honestly, how can any model exist only out of one component? I don’t see how there are models that are not componential models, but maybe that is me.

According to Sternberg (2011), componential models or theories on creativity describe ‘six distinct but interrelated resources: intellectual abilities, knowledge, styles of thinking, personality, motivation, and environment.’ (Sternberg, 2011: p. 227).

Amabile’s componential model incorporates all these resources, some more explicit, some more implicit as part of other components.

Amabile’s definition of creative performance

Amabile’s research focusses on creative products. The process that leads to those creative products she calls creativity. Her definition of creativity is as follows (Amabile, 1996: p35):

A conceptual definition of creativity that comprises two essential elements:

A product or response will be judged as creative to the extent (a) it is both a novel and appropriate, useful, correct or valuable response to the task at hand, and (b) the task is heuristic rather than algorithmic.

If we zoom in on this definition we firstly see that she focusses on the right side of our equation on creativity (CQ14), on the outcome not on the process.

Secondly, heuristics comes from the Ancient Greek word for discovery or finding. You might see the comparison with Eureka, the same linguistic background. Heuristics is a method to solve a problem based on what you know from other problems you’ve solved. Algorithmic tasks are rather straightforward, the method that is needed to solve the problem is known.

How heuristics are part of Amabile’s theory, we will find out.

Amabile’s basic assumptions

Amabile (1996) describes ten assumptions or observations as the starting point. I will give you the relevant ones for this article (Amabile, 1996: pp. 82-83).

- Everyone can be creative to some extent. There are different levels of creative performance.

- The level of education you need for creative performance differs per domain.

- To be talented, educated, and to have a set of cognitive skills is not enough for creativity. If you wonder what she means with ‘cognitive skills’, I’ll get to that.

- Incubation might exist but creative performance is for a large part a result of hard work.

I think it is good to keep these assumptions in mind. They are not difficult to follow but we can think of arguments against all these assumptions. Finally, we get to her model.

The three components of Amabile’s componential model

Amabile’s componential theory exists out of three components that are necessary to achieve creative performance (Amabile, 1996):

- Domain-relevant skills. These skills ‘comprise the individual’s complete set of response possibilities from which the new response is to be synthesized,[…] (Amabile, 1996: p.85).

- Creativity-relevant skills. ‘An individual’s use of creativity-relevant skills determines the extent to which his product or response will surpass previous responses in the domain’ (Amabile, 1996: pp .87-88).

- Task motivation ‘includes motivational variables that determine an individual’s approach to a given task’ (Amabile, 1996: p.83).

I discussed the different arguments for creativity as a generic trait or a domain-specific trait (CQ13). With domain-relevant skills and creativity-relevant skills, Amabile goes for a combination of the two.

However, her research focused on the third component, the role of motivation for creative performance. She doesn’t elaborate on what differentiates between creativity-relevant skills from domain-relevant skills (Baer, 2010). This is something to keep in mind.

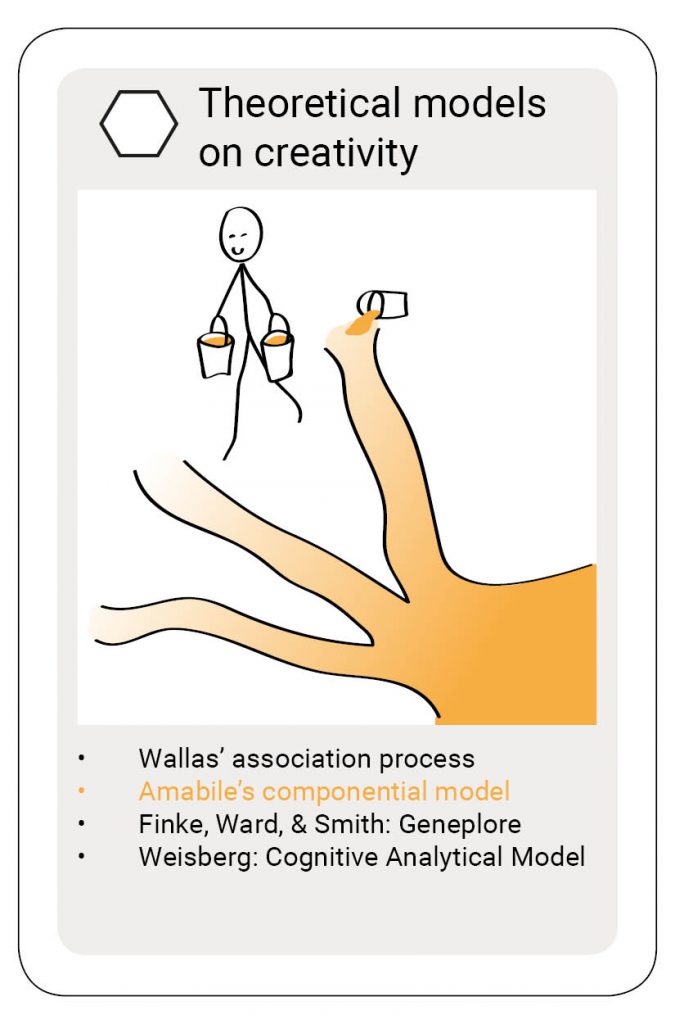

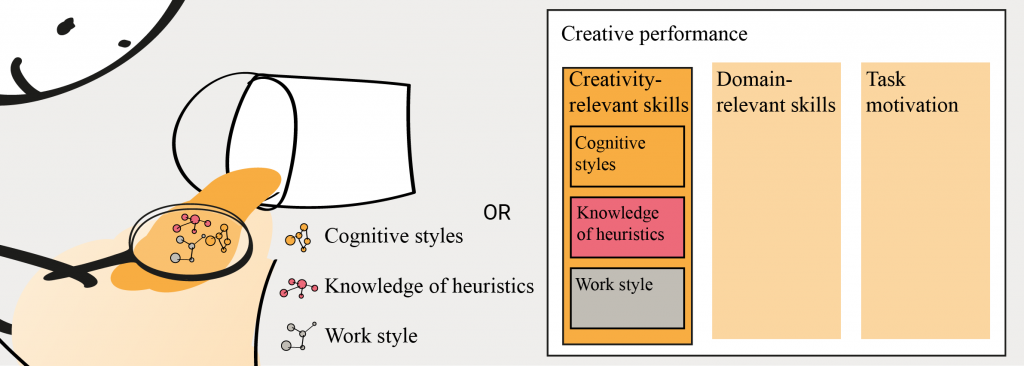

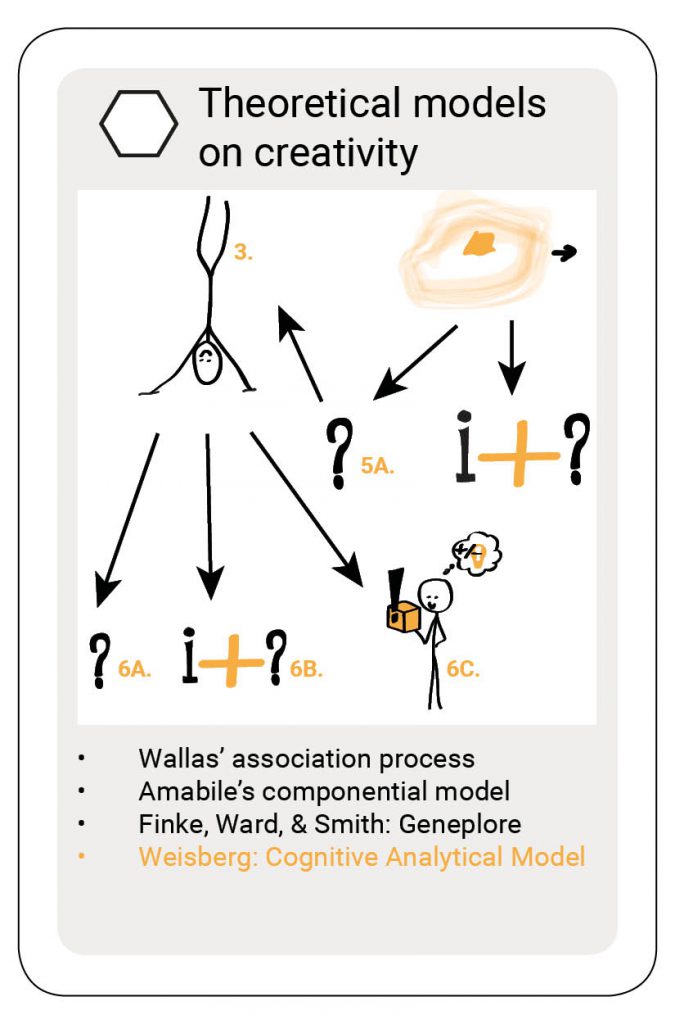

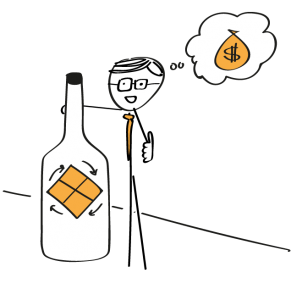

Figure 2 showcases these three components through a metaphor and in a more scientific abstract kind of way. I obviously prefer the first, because it is more creative ?.

Figure 3 I copied from Amabile (1996, p.84). In that figure, you will also find the subcomponents of each component.

Figure 2: The buckets that fill the pool of creative performance OR the three components that form creative performance

| Includes: | Depends on: | |

| Domain-relevant skills |

Knowledge about the domain Technical skills required Special domain-relevant “talent” |

Innate cognitive abilities Innate perceptual and motor skills Formal and informal education |

| Creativity-relevant skills |

Appropriate cognitive style Implicit or explicit knowledge of heuristics for generating novel ideas Conducive work style |

Training Experience in idea generation Personality characteristics |

| Task motivation |

Attitudes toward the task Perceptions of own motivation for undertaking the task |

Initial level of intrinsic motivation toward the task Presence or absence of salient extrinsic constraints Individual ability to cognitively minimize extrinsic constraints. |

Figure 3: Components of Creative Performance, based on Amabile (1996: p.84), figure 4-1.

In this article, I will only discuss the second component, the creativity-relevant skills. I can’t fit a discussion on all three components in 3000 words. It would be more logical to focus on the role of task motivation because this component researched extensively. However, her work on the role of motivation is widely available, yet her opinion on creativity-relevant skills is less known. Also, I have a chance to discuss the role of motivation in chapter 8.

Moreover, if we understand these creativity-relevant skills we might be able to train them as well. Exciting! Let’s see what in that ‘creativity-relevant skills bucket’ that flows into the Pool of Creative Performance (see figure 4).

Figure 4: focus on the bucket of creative-relevant skills, or focus on the component of creativity-relevant skills

Creativity-relevant skills

As shown in figure 3, Amabile names three subcomponents that form the component of creativity-relevant skills:

- Cognitive styles.

- Knowledge of heuristics

- Work style

Because Amabile has a Bachelor’s degree in Chemistry. I think adding molecules to the picture is a nice touch, see figure 5. We’ll start with the cognitive styles.

Cognitive styles

Amabile (1996) describes these cognitive styles by ‘a facility in understanding complexities and an ability to break set during problem-solving’ (Amabile, 1996: p.88). I don’t know what a cognitive style is. My best guess that cognitive styles define ways of thinking. Please, enlighten me if you have the answer.

Amabile gives nine relevant features of cognitive style. In these nine features we see a variety of theories passing by. I will mention and shortly comment on these features. Then I will draw my conclusions for these cognitive styles

Breaking perceptual set

Remember the Gestalt theory on Creativity? If not, see CQ11. This feature is in line with that theory. The famous phrase ‘Looking differently at the same thing’ summarizes this feature. There are methods available for us to train ourselves in doing this. Amabile describes some of these methods in her chapter on how to enhance creativity. I’ll get to that.

Breaking cognitive set

This feature is about finding new strategies for problem-solving. Amabile bases this feature on Newell et al. (1962). You might remember those fellows from CQxx. I will elaborate on their theory in the next chapter.

The difference in breaking perceptual set and breaking cognitive set is a difference in thinking about what you perceive and thinking about how you approach a problem.

Understanding complexities

Amabile refers to Quinn (1980) to support her claim. Unfortunately, I have no access to that article, there is only a short abstract online. According to Quinn (1980) understanding complexity contributes to creativity, at least in the linguistic domain. I don’t know how Quinn defined creativity.

Keeping response options open as long as possible

That is a pretty straight forward feature and based on two other famous persons in creativity research land: Getzsels & Csikszentmihaly (1976). It is a shame I cannot access that article, I would like to read how to judge rather I am keeping my options open long enough or when I am keeping my options open too long. That would interesting information. This feature also reminds me of the next feature, that we all know.

Suspending judgment

Among others, Amabile refers to Alex Osborn (1963)* to back up this feature. We don’t see that happening often, a theorist that refers to a practitioner. There are multiple principles behind this feature. Osborn calls it ‘judicial judgment is ruled out’ (Osborn, 1948: p.269). I will elaborate on the principles behind postponing judgment in the article on brainstorming.

*Applied Imagination is from 1953. Amabile used the revised version from 1963.

Using “wide” categories

Amabile refers to an argument by Cropley (1967) (again I have no immediate access to this source). She says that he said (I feel like I’m referring to an argument between little children…), that people who use wider categories are more likely to produce creative results than those who use more narrow categories. You can see a category as ideas that can be grouped together. In workshops, we often call them clusters.

Clustering is a technique we use after idea generation to have participants in a workshop decide what ideas ‘belong together’. Guilford (1950, 1968) argued that the more categories you were able to produce, the higher your creative potential (CQ4 and CQ16). Sometimes I use this argument as a competitive element between teams. The team with the most clusters are most creative! That is not true of course, but it’s a good laugh.

However, if we follow Cropley’s (1967) argument, the team that would be the most creative is the group that fits all ideas in one cluster. I’ve noticed this paradox in Guilford’s theory before. Do you see it? If you come up with ideas in many categories, you could argue that you make no connections between ideas because they all seem separate to you. That means that creating many categories is less creative than creating a few categories.

However, I think that Guilford and Cropley actually mean the same. It is about the ability to come with ideas that are associated in a way that is not logical for most of us. Cropley (1967) refers to them as a wide category. For Guilford, these would be different categories. Since I did not read Cropley (1967) I can’t be sure, this is my assumption.

Remembering accurately

According to Campbell (1960), people who are good at remembering details have a greater chance of getting to a good idea that those who are not so good at that. Campbell (1960) is an often quoted paper in creativity research land. Campbell takes a Darwinian approach: strong ideas survive, weak ideas die.

His paper called ‘Blind Variation and Selective Retention in Creative Thought’ had a big influence on Dean Keith Simonton’s theory of creativity.

In my words, it comes down to the more information you can turn into knowledge (thus transform and remember in a way that is understandable for you), the more knowledge you have. And the more knowledge you have, the greater the resources to tap into.

Breaking out of performance “scripts”

Performance scripts are ways of doing things that you know lead to a good result. These scripts are related to the domain. Domain-relevant skills include the knowledge of certain procedures in that domain. Amabile refers to these as ‘scripts’, based on (Schank & Abelson, 1997). I didn’t take the time to find this article.

I see a lot of resemblance with ‘breaking a cognitive set’. I think breaking with these scripts is a special type of cognitive set to break with. The script refers to a certain cognitive set that is particular for a domain. For example, the script for writing a pop song or the script for solving a mathematical problem.

Perceiving creatively

In the explanation of this feature Amabile (1996) refers to Koestler’s (1964) bisociation theory. In simple wordings, it means ‘looking at the same thing and seeing something different as anybody else’. I will elaborate on Koestler in the article on bisociation, somewhere in the fall.

Conclusions on cognitive styles

Amabile is obviously going for a ‘breaking with the past’ approach, by saying that we need a cognitive style that helps us to break-set in problem-solving. She is also saying that we need a cognitive style that helps us understand complexity (Amabile, 1996: p.88). Generally, I think she is short with her explanation of these cognitive styles. I was hoping for more clarity. I probably should read the book from A to Z.

Also, I like to challenge the first approach. We can never truly break with the past, we are always building on the past, even if we reject actions or ideas from the past.

I understand that it is easy to say in a workshop: let’s do things differently! Original ways of doing might lead to original results, right? But you can only ‘do things differently’ or to ‘think differently’, if there was a ‘normal’ way of doing in the first place. Remember that ‘normal’ is the ‘different’ of the past. That’s how history develops. But even when, this ‘different way of thinking or doing’ is somehow different from previous ways of doing, it is also similar. We use our same hands, hearts, and heads. I would like to know when different is different.

Finally, she gives some features that might contribute to understanding complexity, like keeping your options open and suspending judgment. Those features help to allow yourself to dwell over a thought. I think that helps because I assume that understanding complexity takes time and by using the features of those cognitive styles (if you can put it like that), I’m buying time.

A quick recap

We have creative performance that can be achieved by three components: creativity-relevant skills, domain-relevant skills, and task motivation. We zoomed in on one component: creativity-relevant skills. That skill exists again out of three sub-components: cognitive styles, knowledge of heuristics, and work style. Then we zoomed in on one of these sub-components: cognitive styles, and we get another nine features. We move on to the second sub-component of the creativity relevant skills: knowledge of heuristics.

I hope you are still with me.

Knowledge of heuristics

Knowledge of heuristics is about the knowledge you have on methods you can use to find answers to a problem. Amabile follows Newell et al. (1962) approach towards heuristics in problem-solving. They defined heuristics as ‘any principle or device that contributes to the reduction in the average search to solution’ (Newell, 1958: p.22)*.

In heuristics, you follow a ‘rule of thumb’ (Weisberg, 2006). That means you have no guarantee for an answer, you choose a strategy that seems the best at the moment.

*Why I keep referring tot Newell and Simon (1958) and most theory to Newell (1962) has a reason. When I see a quote I look up the quote in the original article whenever I have the change. I found this article only in the conference version from 1958. I guess is that this article was first a conference article that got published a few years later. As far as I can tell, the content is the same.

Amabile refers to creativity heuristics as heuristics that ‘are best considered as ways of approaching a problem that can lead to set-breaking and novel ideas, rather than as strict rules that should be applied by rote.’ (Amabile, 1996: p.89). She doesn’t say what those approaches are. If we read her description of creativity heuristics it seems as if creativity heuristics are the heuristics that lead to certain cognitive styles (the breaking styles).

In her chapter on the implications for enhancing creativity, she gives us some examples of creativity heuristics (Amabile, 1996: p.255). These examples must sound familiar to any creativity practitioner:

- Take a step back, rearrange your elements, see what you have, and define the most important elements.

- Start with the value of an idea and not with how realistic it is. This will come later. Amabile refers to Edward de Bono to back up this example.

- Use concentrated work sessions rather than distribution work sessions and warm-up before idea generation.

- ‘Try something counterintuitive’. Amabile refers to Newell et al. (1962) again.

- ‘Make the familiar strange and the strange familiar’’ Amabile refers to Gordon’s (1961) Synectics. In the next chapter, I will devote an article on synectics.

- And seven can be summarized by ‘experiment & play’.

The third sub-component is work style.

Work style

Amabile devotes only half a page to explain work style. The term is not even part of the index. It is mainly an introduction to her theory on the role of motivation in creative performance. Again she gives a set of features that I will quote Amabile (1996: pp.88-89):

- ‘ability to concentrate effort and attention for a long period of time’

- ‘an ability to use “productive forgetting” when warranted’

- ‘a persistence in the face of difficulty’

- ‘a high energy level, a willingness to work hard, and an overall high level of productivity’

Conclusions

If I zoom out and look at these creativity relevant-skills from Amabile I mainly see a combination of the Gestalt view on problem-solving and the approach to creative thinking by Newell, et al. (1958). I was hoping for another perspective. Of course, I’ve only skimmed the surface of her theory. Maybe there is more in the book that I’ve missed in my research for this article. If you have read the entire book and you have something to add, please tell me!

Next week we are going to take a look at Geneplore, a strategy that exists out of generating options before exploring them. Hopefully, I will feel more inspired after finishing next week’s article. As always you will find the cards for the upcoming weeks below.

By the way, I split the reference list into two. In the first part, you can find the references I for this article and in the second part, you can find Amabile’s references that I mentioned in this article.

Willemijn

The creativity quartet combines my knowledge of and experience with creativity. Just like any other person I have experience with creativity as long as I live, but more deliberate when I started studying Industrial Design Engineering in 2001. I have over fifteen experience in facilitating and training creativity. My interest in creativity theory started in 2015. And I’m currently looking into doing promotional research on creating an overview of creativity theories. What you read in the articles are my interpretations of the truth. If you have something to add to that, please do so. Ending with my favorite quote on creativity by Maya Angelou:

“You can never use up creativity. The more you use, the more you have.”

References used in this article

- Amabile, T. M. (1996). Creativity in Context. New York: Avalon publishing.

- Baer, J. (2010). Is Creativity Domain Specific?. In Kaufman J. C., and Sternberg, R. J. (Eds.). The Cambridge Handbook of Creativity, pp.321-341. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, D. T. (1960). Blind variation and selective retention in creative thought as in other knowledge processes. Psychology Review, 67(6), pp. 380-400.

- Guilford, J. P. (1950). Creativity. American Psychologist, 5(9), pp. 444-454.

- Guilford (1968). Creativity, intelligence, and their educational implications. San Diego, CA: EDITS/Knapp.

- Newell, A., Shaw, H. A., Simond H. (1958, May). The process of creative thinking. Paper presented before symposium at the University of Colorado.

- Osborn, A. F. (1948). Your Creative Power. New York: Scribner Press. 6th print.

- Osborn, A. F. (1953). Applied Imagination: Principles and Procedures of Creative Thinking. New York: Scribner Press. 9th print.

- Sternberg, R, J. (2011). “Componential Models of Creativity”. Encyclopedia of Creativity: Second Edition, eds. Runco, M. A. and Pritzker S.R., London, UK: Academic Press, 2011, Vol 1. pp. 226–230.

- Weisberg, R. W. (2006). Creativity: Understanding Innovation in Problem Solving, Science, Invention, and the Arts. New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons Inc.

References mentioned in this article, used by Amabile (1996)

- Cropley, A. (1967). Creativity. Longmans, Green.

- Getzsels, J., and Csikszentmihaly, M. (1976). The creative vision: a longitudinal study of problem-finding in art. New York: Wiley-Interscience.

- Koestler, A. (1964). The act of creation. New York: Dell.

- Newell, A., Shaw, J., and Simon, H. (1962). The process of creative thinking. In H. Gruber, G. Terrell, and M. Wertheimer. (Eds.). Contemporary approaches to creative thinking. New York: Atheron Press.

- Quinn, E. (1980). Creativity and cognitive complexity. Social Behavior & Personality: an international journal, 8(2), pp. 213-215.

- Schank, R., and Abelson, R. (1977). Scripts, plans, goals, and understanding. Hillsdale, New Jersey: Erlbaum.

Tags:

SUGGESTIONS FOR FURTHER READING

CQ13: Could Einstein paint like Picasso?

Could Einstein paint like Picasso? No. And Picasso was no brainiac like Einstein was. We give both men credit for their great creative contributions,

CQ23: Creative Problem Solving, the ins and outs

As the term implies, CPS is a method to train people on how to enhance their creativity and become more ‘creative’ problems-solver. I am positive that

CQ5: Creativity is thinking outside the box. But which box?

The phrase ‘outside the box’ is often associated with creativity. Besides outside the box thinking, there are outside the box methods, outside the box

Title photo

Inspiration for inspiration

Would you like to receive the Creativity Quartet 2020 as inspiration? Think about how you can inspire us. For example, we have a coffee, you send us a book or article, link us to a person, point us to a website, etc. Leave your name and e-mail address and we’ll contact you for further information. We will not use your e-mail address to send you offers and won’t give away your information to other parties.